Table 1. Model of Natural Narrative (Labov, 1972, as cited in Simpson, 2004, p. 114)

The 21st century has witnessed the emergence of the very short story (or “short” short story) genre called flash fiction, which has been receiving considerable attention in the digital age. Although flash fiction is a short form of narrative that may be told in less than 700 or 100 words, it is assumed to have the essential story details, and stylistic and structural features compatible with its brevity ( Ben-Porat, 2011; Guimarães, 2010; Nelles, 2012; Taha, 2000). Likewise, flash fiction has found its niche in various anthologies, magazines, websites, and even in academic courses. This paper endeavors to examine the narrative structure of ten flash fiction (or “short” short stories) works written by Filipinos in the anthology ‘Fast Food Fiction Delivery: Short Short Stories to Go’ published in the Philippines in 2015. Using the schematic structure of short stories proposed by Wong and Lim (2014), the study aims to shed light on these research questions: (1) What is the generic structure of flash fiction written by Filipino authors in terms of moves and steps?; and (2) How does the generic structure of flash fiction reaffirm or detract from the structure of a regular short story? In regard to this first objective of the present study, it was found that generally, the flash fiction pieces under consideration incorporate the five communicative moves based on Wong and Lim's (2014) framework: Move 1 - Establishing a context, Move 2 - Indicating a rising action, Move 3 - Delineating the climax, Move 4 - Indicating a falling action, and Move 5 - Providing a resolution. Four steps have been identified as obligatory: 'describing a setting,' 'describing a character,' 'describing a complicating event,' and 'describing effects of a complicating event.' The move-step analysis conducted in the corpus would likewise prove that Filipino flash fiction adheres to the traditional or regular short story structure. The generic structure of Filipino flash fiction provides a complete story with a beginning, middle, and end; thus, it has the story elements of context, which includes the setting and the character(s); rising action; climax; falling action or denouement; and resolution. Lastly, with focus on narrative structure, this paper discusses the place of flash fiction in writing pedagogy.

A narrative depicts several aspects of human experience. It can be oral or written, minor or major, formal or informal, and literary or nonliterary. The word 'narrative' can have varied definitions depending on contexts. Abbot (2002) defines it as the representation of an event or action, or a series of events or actions. Butt, Fahey, Feez, Spinks, and Yallop (2003) specifically define it as a type of texts that “construct a pattern of events with a problematic and/or unexpected outcome that entertains and instructs the reader or listener” (p. 9).

Narratives have been explored in different fields, such as narratology ( Genette, 1980; Propp, 1928/1968, as cited in Simpson, 2004), stylistics ( Culpeper, 2009; Mahlberg & Smith, 2012; Toolan, 2006), cognitive research ( Emmott, 1997; Fludernik, 1996, 2003; Nair, 2003), and sociolinguistic narrative research ( Labov, 1972, as cited in Simpson, 2004; Labov & Waletzky, 2003 [1967]; Richardson, 1990). Within the discipline of literary studies, narratives may cover novels, short stories, and biographies ( Abbot, 2002) because in some cases narratives are considered as a “straightforward, objective recounting of events” (McWhorter, 2001, p. 107), they generally manifest specific linguistic codes. For instance, some hypothetical narratives are told in the future tense, whereas dramatic narratives are presented using the present tense, which is called “the historical present” ( McCabe & Bliss, 2003, p. 4). However, because narratives can tell real or imagined memories of events that happened, they are usually narrated in the past ( McCabe, 1991). As a distinct type of writing, a narrative, according to Toolan (1996), notes the movement, that is, the sense of a “before and an after” condition that something happened, and that “something that happened needs to be interesting to the audience, and interestingly told” (p. 137).

Sociolinguist William Labov (1972, as cited in Simpson, 2004) was one of the first linguists who attempted to explore the structure of narrative. He called his model natural narrative, which has been proved as a productive model of analysis in stylistics (Simpson, 2004). Such an appeal of Labov's model could be attributed to its origins that emphasized the everyday discourse practices of real speakers in actual social contexts. By gathering hundreds of stories casually told by informants from different backgrounds, Labov was able to draw the recurrent features that typify a natural narrative. Table 1 shows the list of the six categories that comprise the model of natural narrative.

Excluding the category Evaluation, the listed categories in the table are sequenced in a way they would occur in a natural narrative. Evaluation is not necessarily located in the central pattern, for it can occur at any stage in a narrative; thus, stylistically, it remains to be a fluid narrative category and may take several linguistic forms based on the evaluative role it plays. The presence of the six categories characterizes a fully formed narrative; however, some or many narratives may lack one or more elements.

Previous studies were also conducted to determine the schematic structures of short stories (i.e., Butt, Fahey, Feez, Spinks, & Yallop, 2003; McCabe & Bliss, 2003; Nunan, 1999). First, Nunan (1999) referred to the information elements of the short story structure as “structure clauses,” which is composed of “orientation, complication, and resolution” (p. 282). Second, Butt et al. (2003) proposed the four structural components of narratives: (1) 'orientation,' an obligatory element that introduces the setting of the story involving 'who,' 'where,' and 'when'; (2) 'complication,' a sequence of events that creates a crisis or problem for the characters; (3) 'resolution,' a component where a problem or crisis is resolved before a normal situation resumes; and (4) 'coda' (optional), which indicates how the characters were changed by the preceding events (pp. 225-226).

Third, McCabe and Bliss (2003) developed a seven-stage model of short story structure: (1) 'openers,' which include a sort of setting up before a stor y begins; (2) 'orientation/description,' the beginning of a story that depicts the background in terms of time, place, and /or characters; (3) 'complicating action,' which pertains to how something occurred; (4) 'climax,' the highest point of interest or intensity in a story; (5) 'resolution,' the point where the problem or crisis ends; (6) 'evaluation,' an explanation why specific events occurred and how the narrator felt about them; and (7) 'closings,' which depict a refusal or inability to continue to narrate or 'codas' that bring the reader back to the point at which the story began.

A recent study by Wong and Lim (2014) examined the generic structure of short stories written by professional textbook writers for second language learners. Using the Swalesian analytical framework, the researchers analyzed 30 short stories based on two criteria: (1) representativity - with reference to lengths (every short story should have fewer than 500 words), themes, settings, and targeted audience; and (2) quality – the stories were written by 21 professional writers from local publishers in Malaysia. The findings revealed that five of the 11 steps were principal rhetorical strategies (i.e., describing a character, justifying an action, indicating a solution to a complicating event, describing the immediate results of a decision, and suggesting an implicit moral element); three were peripheral (i.e., elucidating the consequence of an action, stressing uncertainty over a situation, and specifying an explicit moral lesson learnt); and three were obligatory (i.e., describing a setting, describing a complicating event, describing effects of a complicating event). In general, the short stories began by establishing the context (Move 1) through the description of the setting in terms of time, place, and weather condition. The salient step in this move was 'describing a character,' a pivotal point where the character's physical characteristics, moods, and actions are presented as essential background information of the story. Subsequently, a rising action (Move 2) took place that involved a complicating event, which gradually built up the difficult situation encountered by the character. This complicating event was generally presented in the form of elucidations of consequences that follow actions and their justifications. In delineating the climax (Move 3), the writers more likely described the effects of a complicating event on the character or the situation. Move 4, which would present a falling action, was usually marked by the tendency to depict the immediate results of a decision. Lastly, in providing a resolution (Move 5), the writers usually gave an implicit commentary about the moral element of the story.

Different models of narrative and schematic structures of short stories have been proposed ( Butt et al., 2003; Labov, 1972, as cited in Simpson, 2004; McCabe & Bliss, 2003; Nunan, 1999; Wong & Lim, 2014). The structures proposed by Butt et al. (2003), McCabe and Bliss (2003), and Nunan (1999) bear specific similarities. Three stages in Butt et al.'s framework (i.e., 'orientation,' 'complicating action,' and 'resolution') can also be found in McCabe and Bliss', and Nunan's generic structures. On the other hand, Wong and Lim's (2004) study adapted the Swalesian move - step analytical framework in examining the generic structure of short stories by professional textbook writers.

The 21st century has witnessed the emergence of the very short story (or “short” short story) genre called flash fiction, which has been receiving considerable attention in the digital age. Although flash fiction is a short form of narrative that may be told in less than 700 or 100 words, it is assumed to have the essential story details, and stylistic and structural features compatible with its brevity ( Ben-Porat, 2011; Guimarães, 2010; Nelles, 2012; Taha, 2000).

Nelles (2012) in his essay “Microfiction: What makes a very short story very short?” describes microfiction or flash fiction as a literary genre by delving into the formal and narrative elements of this distinct short story. He argues that the quality of a short story does not depend on pages but on its narrative qualities. He further elaborates this argument by raising the following points: (1) “the actions narrated in microfictions are likely to be more palpable and extreme” in which something significant happens that allows readers to be emotionally involved with a specific character (p. 91); (2) unlike short stories, which often portray a fully delineated character, microfiction typically presents anonymous characters (usually adults of unspecified age) both literally and figuratively, and “situation tends to replace character, representative condition to replace individuality” (Howe, 1982, as cited in Nelles, 2014, p. 92); (3) while classic short stories catalogue a density of details about the setting, microstories just provide “the familiar and representative,” a feature that is closely tied to the genre's brevity (p. 93); (4) the time span or duration of the discourse in microfiction is extremely brief, but some writers can find ways “to keep the duration compressed” (p. 93); (5) microstories very often use intertextual references (explicit or implicit), but if there is any attempt, pop culture or history clichés are used; and (6) the closure frequently relies on open or surprise and abrupt endings, which seem integral to most successful flash fiction.

In a paper presented at the 2nd Human and Social Sciences at the Common Conference 2014, Lucht (2014) discussed the development of flash fiction as influenced by the fastst moving 21st century digital age in which readership has been conditioned by internet usage and software applications. He believes that since it is a “concise fictional text,” flash fiction can be read and enjoyed in a short or very short span of time. Because of this, the use of flash fiction in the classroom becomes productive when introduced to learners, giving them opportunities to apply their knowledge and skills in literary criticism, media, and language, and creative performance.

In her review of the anthology Quick Fix: Sudden Fiction (translated by Rhonda Dahl Buchanan) by Ana María Shua, an Argentine writer who has published more than 80 books in various genres, including novels, short stories, and microfiction, Barr (2010) states that extremely short stories of not more than 200 words have become popular around the world, particularly in Latin America - mentioning that El País annually holds a contest and publishes the best microfiction in one issue of its Sunday magazine and that recognized authors of the genre have published their works, such as the shortest of the minicuentos by Augusto Monterroso (1996), whose story “The Dinosaur” consists of eight words: “When he awoke, the dinosaur was still there” (p. 42). In fact, in Latin America, the first collection of these very short stories was a collaboration by Bioy Casares and Borges published in 1953. Even in Spain and Latin America, the term used for this genre varies: minicuentos, nanocuentos, cuentos brevísimos, and many others. Barr (2010), however, points out that, “Whatever they may be called, the point of microfiction is to have a plot, setting and a denouement all within the briefest narration. They are not jokes nor extended plays on words... the stories should be able to stand alone” (p. 216).

Guimarães (2010) in his study “The short-short story: A new literary genre” proposed a new postmodern prose fiction genre, which is the short-short story. According to him, this genre has emerged only in recent decades as an offshoot of modernism, primarily through Anton Chekhov's fictive works, which brought new trends and techniques to short fiction. Chekhov's distinct writing style of “dismantling the highly-plotted stories and the traditional form” has influenced several modern and postmodern writers, including would-become short-short authors such as Raymond Carver and Robert Coover (p. 64). The findings of the study revealed the features of short-short stories that generally characterize postmodern fiction: reality as a fictional construct, and character as mood; minimally developed form; and a familiar setting with a strange psychic space. In particular, the short-short story “is deliberately unconventional, eccentric, and formally experimental... always condensed, making use of colloquial language. The characters are not welldeveloped within the confines of space but are used as tools to move the plot along” (p. 64). In most cases, too, the outcome implies a parable or suggests a familiar saying, which may be ironic. Also, black humor is often used as a technique to achieve tone and effect, specifically in flash fiction.

In a paper presented at the Atas do Simpósio Internacional “Microcontos e outras microformas,” Ben-Porat (2011) discussed her experimental and comparative study of very short (six-word long) micro-stories, which yielded the following findings: (1) brevity is observed in the poetics of microstories and the modality of their reading as influenced by the digital era; (2) emotional involvement is the strongest agent in turning nano-texts into stories based on readers' perception; (3) the shortness of micro-stories not just hooks the readers but also recruits them to become active coauthors who provide the necessary elements that define a story; and (4) while the use of allusions may be an effective narrative tool, authors of micro-stories face difficulties on how to expand local contexts to trigger the readers' empathy or curiosity. Based on the findings, Ben- Porat claims that nano-literature can be complex, yet interesting and artistic, and might become an avenue for artistic expression in the digital age.

Taha (2000) in her study “The modern Arabic very short story: A generic approach” described the character of the very short story in relation to its reader by examining its formal, stylistic, structural features, and literary techniques. In terms of 'brevity devices,' paralipsis, summary, and ellipsis were commonly used. Paralipsis refers to the limiting of data about characters and their identities (e.g., age, social status, etc.); summary involves “reporting and telling to provide only basic and primary details” (p. 64); and ellipsis is typically used to skip periods of time, leaving much gap or space for the text's interpretation. Typical, too, in the analyzed Arabic very short stories was the use of a 'reactive character,' in which the text focuses on a character's behavior as if he or she were being tested. “The text itself is important, but the character's behavior in this test is more important since this is a very short story” (p. 66). Another literary technique that complements the brevity of this genre as revealed in the study was 'making strange,' which presents less explicit and less direct data about the story, but involves the reader to interpret the unfamiliar yet symbolic text. Further, motif and leitmotif recurred as 'noticing' devices in the very short stories. These techniques can restrict the length and focus of a text and may lend themselves well in activating the reader's participation in text interpretation. Unlike the closed ending, the use of open ending in the short stories analyzed would tend to “transfer part of the writing process to the reader,” that is, supplying the missing details or parts or providing the closure (p. 72). Lastly, the study proved that very short stories work like poetry in terms of lyrical diction, i.e., the poetic dimension and the figurative language of very short stories complements the required minimalism of the genre.

Because of its ongoing 21st century digital-age popularization, flash fiction as a literary genre has not yet been extensively explored. Most related investigations about flash fiction were on literary genre studies (Ben-Porat, 2011; Guimarães, 2010; Lucht, 2014; Nelles, 2012; Taha, 2000) and very few on its use in writing pedagogy (Batchelor & King, 2014; Lucht, 2014).

An informal survey the researcher conducted revealed that students and teachers alike appear to be unfamiliar with flash fiction as a literary genre; some are also 'baffled' by the language code of the said genre perhaps because of its unconventional techniques of narration. Herein lies the challenge that the flash fiction genre hurls, especially at the young reader; that is, the writer's creativity likewise demands creativity from the reader. Thus, this paper aims to add to the relatively increasing number of studies concerning flash fiction.

Specifically, the present study attempts to shed light on these research questions:

Lastly, with focus on narrative structure, this paper discusses the place of flash fiction in writing pedagogy.

This section presents the theoretical paradigm of the study in describing the generic structure of flash fiction guided by the principles concerning the schematic structure of short stories (Wong & Lim, 2014).

Wong and Lim's (2014) Schematic Structure of Short Stories

In order to address the first research question, this paper considers the schematic structure of short stories proposed by Wong and Lim (2014, see Table 2) in their study “Linking communicative functions with linguistic resources in short stories: Implications of a narrative analysis for second language writing instruction,” which examined 30 short stories (fewer than 500 words in length) written by 21 professional textbook writers. Such a model differs from those in previous studies (e.g., Butt et al., 2003; McCabe & Bliss, 2003; Nunan, 1999) because it features not only the major moves in the narrative structure but also the constituent steps under each move [thus, adapting Swales' (1990; 2004) move-step analytical framework].

Although the moves used in Wong and Lim's study might, at first glance, appear to be the same with the elements of short stories revealed in the past studies mentioned above, the use of present participial phrases (e.g., 'stressing uncertainty over a situation,' describing the immediate results of a decision') for the rhetorical stages (similar to those in Swales' analytical framework) can clearly illustrate the rhetorical functions of the segments of a narrative text.

Both quantitative and qualitative approaches were utilized to analyze the generic structure of flash fiction in terms of moves and steps.

The flash fiction pieces (or “short” short stories) under study were taken from the anthology Fast Food Fiction Delivery: Short Short Stories to Go, which was published in the Philippines by Anvil Publishing, Inc. in 2015. Noelle Q. de Jesus and Mookie Katigbak-Lacuesta co edited the said work, which is a follow-up to 2003's first-ever published collection of flash fiction pieces, Fast Food Fiction: Short Short Stories to Go (by the same publisher, but with Noelle Q. de Jesus as the sole editor), and which features the works of Gemino H. Abad, Jaime An Lim, Gregorio C. Brillantes, Rofel G. Brion, Jose Y. Dalisay Jr., Scott Garceau, Cecilia Manguerra Brainard, Fran Ng, Floy C. Quintos, Nadine Sarreal, Lakambini Sitoy, Ramon C. Sunico, Jessica Zafra, and many more. The new book (i.e., the second collection of flash fiction works), from which the present study's corpus was taken, features roughly 500-word “short” short stories written by 68 Filipino authors. Likewise, this book became a finalist in the 35th National Book Awards for the category Best Anthology in English. It should be noted that this new collection has been considered in the present study based on recency; such an anthology published in 2015 seems to keep up with the 21st century digital popularization of flash fiction as a literary genre.

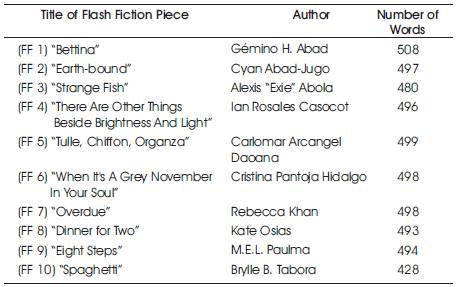

The “short” short stories included in the present study were chosen based on the following criteria: (1) typicality of the genre under study (400-650-words only); (2) inclusion in the anthology of flash fiction, Fast Food Fiction Delivery: Short Short Stories to Go; (3) representation of the works of respected Filipino writers who have won in the prestigious Don Carlos Palanca Memorial Awards for Literature; and (4) representation of flash fiction works written by artists of various ages, gender, and persuasions. Initially, 25 flash fiction pieces from the mentioned anthology qualified for inclusion in the study based on the abovementioned criteria. A random sampling through the fishbowl or lottery technique was done to select the ten (10) representative flash fiction works. In this paper, each flash fiction piece is labeled with a code, for example, FF 10 means flash fiction 10. Table 3 presents the ten flash fiction pieces studied.

FF 1 “Bettina” by Gémino H. Abad centers on the boyhood experience of Noli and his first awakening to a girl named Bettina.

Cyan Abad-Jugo's “Earth-bound” (FF 2) is a story about falling in love even in old age; it depicts the evident unease of a woman in maintaining her intimate relationship with a younger man.

FF 3 “Strange Fish” by Exie Abola chronicles a life with and without love; the protagonist's lover is in Paris, and he is with another girl.

In Casocot's “There Are Other Things Beside Brightness And Light” (FF 4), the narrator recalls the first time he ever felt pain when he was a nine-year-old boy, after witnessing how his father shot his [the boy's] Pomeranian in a boring drunken episode.

Daoana's “Tulle, Chiffon, Organza” (FF 5) captures Julia's ambivalence in making choices in her life, which include her own marriage. The story captures her struggle to convince herself to take the next steps toward the altar in her own wedding.

Cristina Pantoja Hidalgo in FF 6 “When It's A Grey November In Your Soul” dramatically tells a story about a grieving narrator who comes to grips with the death of a very old friend.

In FF 7 “Overdue” by Rebecca Khan, the protagonist finds the overdue book The End of the Affair by Graham Greene, which Hannah left in the apartment after suddenly moving out months ago. To her shock, the protagonist discovers on a page a photo inserted like a bookmark, and a line highlighted on that page reveals Hanna's secret love for her.

In “Dinner For Two” (FF 8) by Kate Osias, the main character, who seems to straddle between reality and imagination, still holds on to hope as she struggles with the untimely death of a loved one, whom she imagines having dinner with.

Paulma's “Eight Steps” (FF 9) highlights the life of Yna who takes on the responsibility of homemaking at a very young age and who strives to manage her own life despite having a dysfunctional family.

FF 10 “Spaghetti” by Brylle B. Tabora shares a story about the protagonist's estrangement from his parents after relaying to them in a “too calm, too casual” manner his classmate's comment that “he might be gay.”

Table 3. The Ten (10) Flash Fiction Pieces under Study

To examine the generic structure of flash fiction in terms of moves and steps, the present study adopted the schematic structure of short stories proposed by Wong and Lim (2014), which follows Swales' (2004) analytical framework. This model is found to be methodically apt because it presents specific functional labels to the constituent steps that indicate precise rhetorical functions of the text segments (or moves) concerned.

In analyzing the generic structure of flash fiction pieces under consideration, a careful examination of the constituent steps in the said corpus was conducted. First, to analyze the steps, each flash fiction was closely read to determine the possible moves and identify their functional labels depending on the communicative functions of the sentences. Swales (2004) defines a 'move' as “a discoursal or rhetorical unit that performs a coherent communicative function” (p. 228). It is a functional unit, that is, a text segment that conveys a speaker or writer's communicative purpose rather than a formal unit (i.e., a textual component constituting a linguistic category, such as a word, phrase, clause, sentence, or paragraph). A move can be realized in the form of a clause at one extreme, and in several paragraphs at the other (Swales, 2004). Next, the steps that indicated a series of strategies employed to achieve each move were then identified.

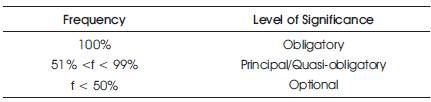

Following Joseph, Lim, and Nor's (2014) study, a three-level system was utilized to determine the significance of moves in the corpus (see Table 4). An 'obligatory' move would occur in 100% of the corpus, whereas a 'principal/quasiobligatory' move would appear in 51% to 99% of the examined texts. On the other hand, a move was considered 'optional' if it occurred in half or less of the flash fiction pieces analyzed. Several studies (Lim, 2010; Parodi, 2014; Tessuto, 2015; Upton, 2002; Yang & Allison, 2003) on ESP move/step analysis relied on the aforementioned percentage of occurrence of moves to determine the 'obligatory,' 'principal/quasi-obligatory,' and 'optional' moves in a genre.

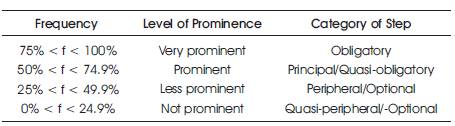

Further, a four-level system from Wong and Lim's (2014) study was adapted (see Table 5) to determine the different statuses of the steps based on their frequencies of occurrence. The following terms were used to identify the extent of use of the constituent steps found in the corpus: 'obligatory,' 'principal/ quasi-obligatory,' 'peripheral/ optional, and quasi-peripheral/ -optional,' which were adapted (i.e., modified) from previous studies (Lim, 2010, p. 231; Wong & Lim, 2014; Yang & Allison, 2003, pp. 372- 374). Computing the percentage of occurrence allowed for the identification of 'obligatory' steps that occurred in most or all of the texts; 'principal/quasi-obligatory' steps that appeared in more than half, but less than 75% of the examined texts; 'peripheral/optional' steps that occurred in less than half of the corpus; and 'quasi-peripheral/-optional' steps that appeared in one-fourth or less of the examined texts.

Table 4. Significance of Moves in the Corpus

Table 5. Level of Prominence of Rhetorical Steps

To guarantee that the rhetorical moves and steps and their respective salient linguistic features in the generic structure of flash fiction were identified with a high degree of accuracy, the intercoding process was done by assigning two independent coders who are knowledgeable in the field of study and who are Assistant Professors of English from a comprehensive university; both are candidates for the degree Ph.D. in English Language Studies in their respective institutions. Only 50% of the corpus, i.e., five (5) out of ten (10) flash fiction writings, was subjected to the intercoding process: FF 1 “Bettina,” FF 2 “Earth-bound,” FF 3 “Strange Fish,” FF 4 “There Are Other Things Beside Brightness And Light,” and FF 5 “Tulle, Chiffon, Organza.” The intercoders were oriented and trained as regards the frameworks for coding and were provided clear instructions on how to identify and code the moves and steps and their respective language mechanisms in the flash fiction works under consideration. The researcher likewise conducted trial sessions with the intercoders prior to giving them two weeks to complete the given tasks independently. Afterward, a meeting was set with the two intercoders to analytically compare and discuss the similarity and difference in the coded moves and steps and their respective linguistic features in the flash fiction's narrative structure. The percentage of intercoder agreement was generally high, i.e., 89.29% to 96.43%. In cases when problems (i.e., difference[s] in the coding) occurred in the intercoding process, a thorough discussion among the coders was held by reanalyzing the questionable data until they arrived at a consensus as regards the results and interpretation of the said data.

This section presents and discusses the findings of the study that substantially address the first research question raised in this investigation, that is, the generic structure of flash fiction written by Filipino authors in terms of moves and steps following Wong and Lim's (2014) schematic structure of short stories.

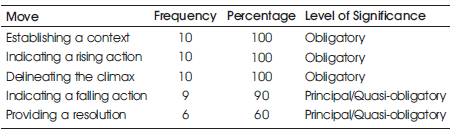

The analysis of the flash fiction (FF, for brevity) pieces under study has shown the five communicative moves incorporated in the corpus: Move 1, i.e., 'establishing a context'; Move 2, i.e., 'indicating a rising action'; Move 3, i.e., 'delineating the climax'; Move 4, i.e., 'indicating a falling action'; and Move 5, i.e., 'providing a resolution.' Table 6 shows the frequencies and percentages of occurrence of these moves in the corpus.

As shown in Table 6, Moves 1, 2, and 3 are obligatory in the ten FF pieces analyzed; this is because these moves appeared in all or 100% of the corpus. Two moves, i.e., Moves 4 and 5, are considered principal, for they appeared in more than half, but less than 75% of the examined texts. Specifically, the moves 'establishing a context,' 'indicating a rising action,' and 'delineating the climax' manifested themselves in all the ten FF pieces (or 100% of the total number of corpus). In addition, the moves 'indicating a falling action' and 'providing a resolution' appeared in nine (or 90%) and six (or 60%) of the total number of FF works, respectively.

However, a few FFs do not have the complete set of moves in their structure, which explains the aforementioned cases of the moves 'indicating a falling action' and 'providing a resolution.' Specifically, FF 3 “Strange Fish,” FF 6 “When It's A Grey November In Your Soul,” and FF 7 “Overdue” hardly contain Move 5 (i.e., 'providing a resolution'); and Moves 4 (i.e., 'indicating a falling action') and 5 (i.e., 'providing a resolution') seem to be missing or are somewhat obscure in FF 9 “Eight Steps.” Assumingly, any story has gaps, and these areas without details or information have to be filled in by readers through their inferential skills. In her essay “Microfiction: What makes a very short story very short?” Nelles (2012) pointed out that the attempt to provide open or surprise and abrupt closures seems integral to most successful flash fiction.

Worth noting, too, are the two FFs, namely, FF 4 “There Are Other Things Beside Brightness And Light” and FF 10 “Spaghetti” that demonstrate an unconventional story structure, for they both begin with Move 5 (i.e., 'providing a resolution'). The following extracts would prove this point:

Extract 1:

“Sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangun.”

- Virgil, The Aenid

Detachment takes practice. (FF 4)

[“Sunt lacrimae rerum et mentem mortalia tangun.” can be translated as “There are tears at the heart of life itself.”]

Extract 2:

The problem wasn't that he didn't make himself clear, but rather the manner in which it was said: too calm, too casual. (FF 10)

The presence of Move 5 (i.e., 'providing a resolution') in the first part of the abovementioned FFs, however, can likewise be considered as 'openers,' which involve a kind of 'setting up' before a story begins (McCabe & Bliss, 2003). They appear to be providing a background through a short summarizing statement before a story commences, and Labov (1972) calls this “abstract” (p. 114).

Table 7 shows the frequencies and percentages of Filipino flash fiction containing the rhetorical steps and their corresponding degrees of prominence.

Move 1-Step 1 (i.e., 'describing a setting'), Move 1-Step 2 (i.e., 'describing a character'), Move 2-Step 3 (i.e., 'describing a complicating event'), and Move 3-Step 1 (i.e., 'describing effects of a complicating event') stand out as very prominent or obligatory steps, for they appeared in all the ten FF pieces in the sample.

Four principal steps, which were frequently utilized by writers in at least 50% of the stories, include Move 3-Step 2 (i.e., 'stressing uncertainty over a situation'), both steps in Move 4 (i.e., 'indicating a solution to a complicating event' and 'describing the immediate results of a decision'), and Move 5-Step 2 (i.e., 'suggesting an implicit moral element').

On the other hand, it can be assumed that Filipino FF writers place less emphasis on elucidating the consequence of an action and on justifying an action when indicating a rising action. Also, the FFs examined hardly contained Move 5-Step 1 (i.e., 'specifying a moral lesson learnt'), which only appeared in two (or 20%) of the corpus, and this can be attributed to the assumption that moral elements are usually incorporated only implicitly through Move 5-Step 2 (i.e., 'suggesting an implicit moral element').

Under Move 1-Step 1 (i.e., 'describing a setting'), '(i) describing a place' is the only substep marked as obligatory as it appeared in nine (or 90%) of the FF works analyzed. Likewise, it would appear that FF writers place less emphasis on 'describing the time' and 'describing the weather condition' when describing a setting. It seems important in a flash fiction to describe where a particular scene takes place. According to Tomasello (2008) and Verhoeven and Strömqvist (2001), a time frame and a spatial or place setting contextualize any form of a narrative. Since FF demands that a writer achieves a great deal in a small space, working on miniatures, or any form of representation seems to be crucial in describing a place setting; thus, such details work by suggestion rather than full description, painting just enough vivid image in readers' minds without clogging the writing with so much details. Nelles (2012) argues that while regular short stories present a density of details about the setting, flash fiction just catalogues “the familiar and representative,” and such a feature is closely linked to the genre's brevity (p. 93). The following extracts illustrate such observations:

Extract 3:

Toward sundown, Noli and his brother Ibs scoured the seashore for prize finds in the sand or among rocks strangled by kelp. In Dumanjug, their house was only a short run to the beach, and soon their friends came running, shouting their names from a coconut grove. Ahead, waving his sando, was lanky Vic, followed by dark, brawny Aning, and trailing behind, Inday, Vic's sister, who had dimples on both cheeks, and her friend Bettina, whose laughter Noli thought he could sometimes hear in his sleep, ringing softly like wind chimes. (FF 1)

In a few details, the underlined words in Extract 3 provide specificity as regards the 'by the sea' setting of the story.

On the other hand, Extract 4, through representation, suggests details that describe the place where a particular scene happens, i.e., a theme or an amusement park. These details are underlined.

Extract 4:

As she tightens her hold around the metal bar, and adjusts her seat on her candy-colored horse, he lays a hand on hers. There is an immediate tingle running up her arm, and she stiffens to rid herself of it.

“Anything wrong?” he asks.

She shakes her head, even as she sees his clean, fair hand upon her dry, brown one. Too veiny. Too withered. Too late.

The merry-go-round progresses at a child's pace, but the time spins past anyway. Like any pleasure. Especially stolen pleasure. (FF 2)

There are instances, however, that important details describing the place setting of FFs are disclosed as the story progresses, and such details are not necessarily found in the first part or paragraph(s), which is usually marked as Move 1 (i.e., 'establishing a context'). The reason for this may be attributed to the close association of the setting, characters, and actions, which are linked as elements in a story (Wong & Lim, 2014). For example, in FF 4 “There Are Other Things Beside Brightness And Light,” more specific details (underlined words) that describe the place where the story happens can be found in the fifth paragraph, although the sentence “Tibby slept at the foot of my bed.” (FF 4), which is a part of Move 1, appears to be a representative detail.

Extract 5:

After mother buried the animal in the backyard near the garbage cans, which were shaded by a hollowed out acacia tree in the dark subdivision where we lived, I finally mustered courage to ask father: “Why did you kill the dog?” (FF 4)

A similar case, which is illustrated in Extract 6, is manifested in FF 6 “When It's A Grey November In Your Soul” where specific details about the story's place setting are mentioned in the fifth and sixth paragraphs.

Extract 6:

This little memorial, held in our old school, is my goodbye. I thought we might say a prayer, share a few stories, read aloud from her latest book. But it's a wet, dreary day. And only four of our friends have come. So few people feel connected to her, or even remember her now. How is this possible? She stayed away too long. She was not on Facebook . . .

It is cold inside this grey-panelled room. Kiko stayed only a few minutes. A meeting, he murmured apologetically. And now, Mila and Au are getting up. Another engagement . . . an urgent errand . . . We touch cheeks lightly. (FF 6)

In addition, as indicated in Table 7 under Move 1-Step 2 (i.e., 'describing a character'), there appears to be prominence put on the substeps 'naming a character,' 'describing the age of the character,' 'describing the mood,' 'describing physical attributes,' and 'describing an action' as they were employed by FF writers in at least 50% of the corpus. Characterization is crucial in making a story compelling. It can be direct, i.e., when an author tells what a character is like; or it can be implicit or indirect, i.e., when an author shows readers what a character is like by portraying his actions, moods, speech, or thoughts. Narratives are agent-oriented (Longacre, 1976); thus, characters as humans are agents or participants who initiate events, and who are influenced by or who react to events.

The emphasis on the use of the substep 'naming a character' in the corpus is indicative of the agent-oriented nature of narratives, with focus on people and their (re)actions. The following extracts show the use of this substep:

Extract 7:

Toward sundown, Noli and his brother Ibs scoured the seashore for prize finds in the sand or among rocks strangled by kelp. In Dumanjug, their house was only a short run to the beach, and soon their friends came running, shouting their names from a coconut grove. Ahead, waving his sando, was lanky Vic, followed by dark, brawny Aning, and trailing behind, Inday, Vic's sister, who had dimples on both cheeks, and her friend Bettina, whose laughter Noli thought he could sometimes hear in his sleep, ringing softly like wind chimes. (FF 1)

Extract 8:

The moment the impossibly-aged doors of the San Agustin Church revealed her, Julia was stunned when she saw the long red carpet (unrolled and laid out just for her) through the ghostly weave of her veil, took her first step and offered a smile. (FF 5)

Extract 9:

It was addressed to Hannah, who, for almost two years, rented the spare room in my off-campus apartment as she was finishing her master's degree. (FF 7)

Extract 10:

Yna stood at the top of the stairs in their rented apartment, looking down at the extension wires crisscrossing the eight steps. (FF 9)

However, there seems to be cases in which the character's name is revealed as the story progresses; thus, such a detail is not necessarily indicated in the first part of FF, which is usually marked as Move 1 (i.e., 'establishing a context'). This, again, is a case of the close link between the characters and prevailing actions that take place in a narrative. Extract 11 from FF 6 “When It's A Grey November In Your Soul” exemplifies this observation. It should be noted that details naming the characters are found in Move 2 (i.e., 'indicating a rising action') of the said FF piece. Extract 12 from FF 10 “Spaghetti” mentions Bert as a character's name in Move 3 (i.e., 'delineating the climax').

Extract 11:

I don't even know why she died. Greg's e-mail gave no details. He never responded to mine. When did she and I last speak on the phone? When did we last exchange e-mails? She said nothing about being ill.

This little memorial, held in our old school, is my goodbye. I thought we might say a prayer, share a few stories, read aloud from her latest book. But it's a wet, dreary day. And only four of our friends have come. So few people feel connected to her, or even remember her now. How is this possible? She stayed away too long. She was not on Facebook . . .

It is cold inside this grey-panelled room. Kiko stayed only a few minutes. A meeting, he murmured apologetically. And now, Mila and Au are getting up. Another engagement . . . an urgent errand . . . We touch cheeks lightly.

Only Anton will stay. His hair is thinning, his shoulders are thicker. I see a pair of spectacles peering over the edge of his white shirt's breast pocket. I want to ask if he ever saw her again after she left for Toronto. Cynthia and I didn't speak of him. I knew she didn't want to, so I kept my curiosity in check. He will stay longer. He loved her. (FF 6)

Extract 12:

— Where did you learn about this, honey?

— I bet it was Bert from the other street?

— Oh, now, let's not point fingers. (FF 10)

Another principal substep, which is 'describing the mood,' is found in Move 1-Step 2 (i.e., 'describing a character). The following extracts with specific suggestive details in underlined words illustrate the said principal step:

Extract 13:

What on earth is she doing?

As if she has just stood up from the depths of a dream and found herself standing here surrounded by children. Their smooth, round faces. Their ringing cries and laughter. Their unguarded glee.

As she tightens her hold around the metal bar, and adjusts her seat on her candy-colored horse, he lays a hand on hers. There is an immediate tingle running up her arm, and she stiffens to rid herself of it. (FF 2)

Extract 14:

A girl, a boy. They sit next to each other on the first day of class. At first they are vaguely annoyed with each other, but the annoyance turns to hostility, then softens into friendship, which blossoms into love. (FF 3)

Extract 15:

The moment the impossibly-aged doors of the San Agustin Church revealed her, Julia was stunned when she saw the long red carpet (unrolled and laid out just for her) through the ghostly weave of her veil, took her first step and offered a smile. (FF 5)

Extract 16:

…The smell makes it easier for her to pretend that she's in a much larger kitchen, in a much more pleasant time. When she looks at the pot simmering with a few cubes of precious meat, she finds it in herself to smile. (FF 8)

It seems possible, however, that details describing or suggesting the mood of a character(s) are situated in other parts of an FF piece, as illustrated in Move 2 (i.e., 'indicating a rising action') and Move 3 (i.e., 'delineating the climax') of FF 5 “Tulle, Chiffon, Organza,” which indicate details in underlined words that imply “lack of freedom” and the idea of marrying someone “against her will.” Extract 17 would prove this assumption.

Extract 17:

… their earnestness and goodwill constricting her throat so much that, to distract herself, she had to cast her gaze on the strings of crystals draped on white branches by the pews. And yet she was not moved to tears, no need to dab the corners of her eyelids with a lace handkerchief, no need to protect the mascara from smudging. She, after all, had a wedding to attend to, her own, a ridiculous proposition three years back when she thought and knew in her bones that she wasn't the marrying type (she hated children, for one, and that one incident with Marco she could not permit herself to remember) and was resolved to the idea of single-blessedness until Rodel came and changed all that. But not everything, she thought. She was clear on not having children and that for her was a nonnegotiable. She agreed to pretty much everything else, however, including having to leave the Philippines for New Zealand where Rodel would be based for the next ten years. Fevered with something close to loneliness, she took the next step, thinking that the wedding was some kind of a going-away party: She would never see these people again, in this kind of arrangement and demeanor, never mind if most of them were strangers; she would never be a recipient of their generosity in the same way again. If only she could dash to the altar and have the ceremony over and done with but the long, long train of her wedding gown, layer upon layer of tulle, chiffon and organza gliding in her wake pulled her senses awake-a rude reminder. (FF 5)

The principal substep 'describing an action' is likewise found in Move 1- Step 2 (i.e., 'describing a character). Such was manifested in six (or 60%) of the study corpus. In here, the focus is on action rather than exposition, that is, letting the characters' actions speak for themselves. In this case, character becomes a potential action (Galef, 2016). As how Henry James in The Art of Fiction notably averred, “What is character but the determination of incident? What is incident but the illustration of character?” The use of a 'reactive character', in which the text highlights a character's behavior as if he or she is being tested, seems typical in FF, just like what was found in Taha's (2000) study on modern Arabic very short stories. Here are examples of the substep 'describing an action' taken from the corpus.

Extract 18:

As she tightens her hold around the metal bar, and adjusts her seat on her candy-colored horse, he lays a hand on hers. There is an immediate tingle running up her arm, and she stiffens to rid herself of it. (FF 2)

Extract 19:

I fed him, I bathed him. Tibby slept at the foot of my bed. (FF 4)

Extract 20:

With practiced efficiency, she grinds a chiffonade of dythlista into a fine pulp. Wafts of the yellow herb's distinctive aroma fill the room, temporarily displacing the scent of meat and sweat and old wood. The smell makes it easier for her to pretend that she's in a much larger kitchen, in a much more pleasant time. When she looks at the pot simmering with a few cubes of precious meat, she finds it in herself to smile. (FF 8)

Extract 21:

Yna stood at the top of the stairs in their rented apartment, looking down at the extension wires crisscrossing the eight steps. She was carrying a pink plastic basin filled with water, rather heavy for her small hands. (FF 9)

Further, both the principal substeps 'describing the age of the character' and 'describing physical attributes' appeared in five or 50% of the total number of FFs. Here are extracts that illustrate the former substep. It should be noted that in some instances, implicit details would suffice for the description of the characters' age.

Extract 22:

She shakes her head, even as she sees his clean, fair hand upon her dry, brown one. Too veiny. Too withered. Too late. (FF 2)

Extract 23:

A girl, a boy. They sit next to each other on the first day of class. At first they are vaguely annoyed with each other, but the annoyance turns to hostility, then softens into friendship, which blossoms into love. By December, they are a couple. Two years later they are juniors. (FF 3) 3

Extract 24:

I was a young boy, and he was my world—a yapping mass of cuteness that required devotion. (FF 4)

Some instances, however, would show that the description of a character's age is revealed as the story progresses; such a detail is not necessarily indicated in the first part of the FF, which is usually marked as Move 1 (i.e., 'establishing a context'). For example, in FF 9 “Eight Steps,” the main character's (i.e., Yna) age is revealed in Move 2 (i.e., 'indicating a rising action'); and in FF 10 “Spaghetti,” the specific detail about the character's age is mentioned in Move 3 (i.e., 'delineating the climax'), as shown in Extracts 25 and 26, respectively.

Extract 25:

Eight steps for her eight years was one of her thoughts. First year with her mom and dad, second year without Mom, third year with quarrelling Mom and Dad, fourth year without Dad, four more years without Dad. Why, four times two equals eight years old, plus one new little brother, and new whatever-wife of Dad, with pending whatever-husband of Mom, God forbid. (FF 9)

Extract 26:

For an eight year old, the conversation was too much for him. The truth is, he hadn't interacted with Bert except maybe for the time he came over their house to hand over a freshly-baked chicken pie his parents made. (FF 10)

The following extracts, on the other hand, show the use of the principal substep 'describing physical attributes' under Move 1-Step 2 (i.e., 'describing a character'):

Extract 27:

Ahead, waving his sando, was lanky Vic, followed by dark, brawny Aning, and trailing behind, Inday, Vic's sister, who had dimples on both cheeks, and her friend Bettina, whose laughter Noli thought he could sometimes hear in his sleep, ringing softly like wind chimes. (FF 1)

Extract 28:

I once cared about a dog named Tibby. It was a white Pomeranian—one of those frivolous types of dogs that are easy to love. The busy brilliance of their thick hair reduces even adults to squealing children. (FF 4)

FF 5 “Tulle, Chiffon, Organza,” however, presents a different case in terms of describing the physical attributes of a character. Such details in the said FF are found in Move 4 (i.e., indicating a falling action), as shown in this extract:

Extract 29:

She had a glimpse of Rodel, her husband-to-be, waiting for her, shifting his weight from one foot to another, his palms solemnly meeting in front of him. How earnest and expectant his face was, how handsome and utterly honest, struck with an understanding of ever y possible hope and disappointment that would fill the near compartment of their days. (FF 5)

It is likewise interesting to note that two other possible substeps may be included under Move 1-Step 2 (i.e., 'describing a character'), namely, 'describing relationship among characters' and 'describing a character's work or profession,' as exemplified in Extracts 30 and 31, respectively.

Extract 30:

Toward sundown, Noli and his brother Ibs scoured the seashore for prize finds in the sand or among rocks strangled by kelp. In Dumanjug, their house was only a short run to the beach, and soon their friends came running, shouting their names from a coconut grove. Ahead, waving his sando, was lanky Vic, followed by dark, brawny Aning, and trailing behind, Inday, Vic's sister, who had dimples on both cheeks, and her friend Bettina, whose laughter Noli thought he could sometimes hear in his sleep, ringing softly like wind chimes. (FF 1)

Extract 31:

It was addressed to Hannah, who, for almost two years, rented the spare room in my off-campus apartment as she was finishing her master's degree. (FF 8)

For some disproportionate sense of duty to the University—where I teach—to locate its missing property, I feel bound to search for the overdue book instead of simply assuming that it was gone along with Hannah. (FF 8)

[It should be noted that the underlined detail is found in Move 2 (i.e., indicating a rising action').]

Earlier, based on the figures relating to the significance of rhetorical steps found in the corpus, it was found that in Move 2 (i.e., 'indicating a rising action'), Step 3 (i.e., 'describing a complicating event) seems to be obligatory. Under such a step, only the substep '(i) referring to a difficult/surprising situation' is obligatory. On the other hand, the substep '(ii) foreshadowing an unexpected event' only appeared in one FF (or 10% of the corpus); thus, it is marked as quasi-peripheral. As a move in the story structure, the rising action exists to unravel the story, that is, developing the conflict and deepening the relationships between, among, or within characters. Simply put, this obligatory element in a narrative, also called 'complication,' provides a sequence of events that creates a problem for the character(s) (Butt, Fahey, Feez, Spinks, & Yallop, 2003). Any great fictive work, regardless of length, demands both tension and conflict to direct the motions of the characters and the plot. The following extract from FF 2 “Earth-bound” presents details that show how a May-December affair or romance [between the age-gapped characters] can spark doubts or struggle within the main character, a sort of internal conflict. Such details under Move 2- Step 3 (i.e., 'describing a complicating event') are marked under the substep 'referring to a difficult/surprising situation.'

Extract 32:

She had wanted to hide away in the crowd, but instead here she is, shining a spectacle of herself.

What does everyone else see? A mother with her teenage boy? What do they think? A depraved woman clawing at lost youth. She clenches her hands and shoves them into her sweater pockets, even as he wraps his arm around her. He probably thinks she is cold. He probably thinks she likes this.

She does.

They stop among the food carts, and line up for cheese-flavored fries. Because she has hidden away her hands, he finds the excuse to feed her. She feels her face burning, but tries not to look around her, to see if anyone is watching. (FF 2)

In FF 4 “There Are Other Things Beside Brightness And Light,” the rising action (i.e., 'referring to a difficult/surprising situation') is presented with a series of details that create suspense and tension among the characters. In the story, the conflict seemed to develop as soon as the father of the main character suddenly shot Tibby (i.e., a Pomeranian, the main character's pet) in a boring drunken episode, as illustrated in this extract:

Extract 33:

… Once, in a boring drunken episode, my father shot Tibby with his gun. He said the dog barked too loudly, it made him spill his beer on his wifebeaters, which barely contained his swollen gut.

Mother told me not to cry. “It would make your father angrier,” she said.

So I didn't cry. I dammed whatever it was that threatened to overwhelm. When father stared at me, as if to taunt me, I held his eyes. I could not be moved. I did not cry. (FF 4)

Also worth noting in Table 7 are the obligatory substep '(ii) 'describing the effect on a character' under Move 3- Step 1 (i.e., 'describing effects of a complicating event'), which appeared in all the ten FFs; and the principal step under Move 3, i.e., 'stressing uncertainty over a situation.' Delineating the climax means establishing the decisive moment or point in the narrative, where a conflict or crisis reaches its peak. In FF 1 “Bettina,” the use of the substep 'describing the effect on a character' seems clear when Noli thought he could show off Bettina his prowess, hence, trying to hold his breath the longest and shouting her name as he plunged (i.e., “taking the plunge” into his feelings, so to speak). But he failed to do so, for he bumped his head against the bamboo. Here is the extract from the said FF piece to prove this point.

Extract 34:

But his head bumped against bamboo he kicked away in panic, but the raft seemed to follow. Must soon draw air! kicking away, kicking . . . (FF 1)

FF 2 “Earth-bound,” on the other hand, offers a different case in delineating the climax; that is, it describes the effects of a complicating event, particularly on a character, and at the same time, stresses uncertainty over a situation. The details in Extract 35 show how the main character, in a single moment, would attempt to resolve the conflict, that is, her being involved in a May-December relationship.

Extract 35:

She stands rooted to the spot, unable to move, unable to breathe without him. She opens her bag and rummages through it, but she doesn't know what she is looking for. She feels the urge to throw it down, to empty it, to run away. (FF 2)

Furthermore, as reflected in the data, both steps in Move 4 (i.e., 'indicating a solution to a complicating event' and 'describing the immediate results of a decision') are marked with a considerable level of prominence or significance in the corpus. This move, which comes after the climax, usually occurs when the conflict or main problem of a story is resolved. For example, Extract 36 from FF 4 “There Are Other Things Beside Brightness And Light,” suggests a falling action that seems to describe the results of the decision made by the main character after witnessing the sudden death of his dog and bravely confronting his father who intentionally shot his pet with his [father's] gun. It likewise highlights the main character who evaluates, at the very least, the significance of such a complicated event.

Extract 36:

I had a hard-on. I remembered that most of all. At nine, I had a fucking hard-on.

Later on, in my quiet days, my imagination tries to spring on me the sound of a dog yelping, in that frightened drawn-out cadence that signals knowledge of pain. But I have learned to drown that out with the white noise of nothingness—a gathering blob of pure vacuum that settles in my head and sits in it like a strange dark dream. (FF 4)

In FF 8 “Dinner For Two,” the main character, who seems to be stuck between reality and imagination, struggles with the untimely death of a loved one, whom she imagines having dinner with. After raising a toast to the empty chair in front of her, a compelling realization sets in. At that point, the story proceeds with the decision made by the character on that situation, as shown in this extract:

Extract 37:

A feeling of dread comes like a bolt of lightning, so unexpected and so very certain, that she blinks. When her vision clears, she sees only that the bowl is chipped, that the basket of bread is small, that the glasses are filled with water and not wine, that the swans look lifeless with their unstarched cloth wings.

But Triktikaran calms her down. The aroma coupled with the perfectly cooked meat barely visible beneath the murky broth helps keep the fear at bay. (FF 9)

Seemingly confused about her disposition having been engaged in a May-December affair, the main character in FF 2 “Earth-bound,” who is trapped between staying and letting go, chooses the former, as revealed by the details in Move 4-Step 1 (i.e., 'indicating a solution to a complicating event') of the story:

Extract 38:

But he comes back. Each time, she thinks, he won't, and then he does. He offers her the cup. As she takes it, he holds her other hand and squeezes. She blinks and points to the Ferris Wheel.

It takes forever to get to the top. He speaks animatedly of the work he has found, that will take him half a continent away. She nods, half-listening, then looks over the tents, the low buildings, the tops of trees, to the dark expanse that is the sea. There are some lights dotting the water, the few boats that are out to sail to that one star in the distance.

He sighs at the star. “It is too far.”

She smiles as it. “It is beautiful in itself”. (FF2)

Lastly, it can be assumed that in Move 5 (i.e., 'providing a resolution'), Filipino FF writers would tend to place more emphasis on suggesting an implicit moral element. The last part of the FF “Bettina” illustrates details that suggest an implied moral element:

Extract 39:

He thought of the shy mollusk dragging its shell across his open palms. Surely it has slithered out of his pocket among their clothes on the beach and found a warm, protective hollow in the sand. (FF 1)

The above extract shows the mollusk surfacing again yet still finding a hiding place, that is, it “found a warm, protective hollow in the sand.” Noli, like the mollusk, had his attempt to show his true feelings for Bettina, but it ended up still hidden. Such is a case of an internal struggle; Noli seems to face the complexity of the adult world and to journey the distant mature self-awareness. As an important message in the story, the “mollusk” will surface once more, and Noli will have his time.

The FF “There Are Other Things Beside Brightness And Light” likewise presents an implied moral element in its Move 5 (i.e., 'providing a resolution), which conveys the main character's epiphany; that is, he must learn how to face the harsh and “dark” realities of life after experiencing trauma and pain the first time. Here is the extract from the said FF.

Extract 40:

And all I will ever learn to see from then on is the dark side to everything. (FF 4)

Table 6. Significance of Moves Found in the Filipino Flash Fiction

The findings of the present study may prove the assumption that Filipino flash fiction follows or reaffirms the structure of a regular short story; and with its brevity, it still shows the necessary story details to convey a dominant impression of life. In fact, in their edited book Flash Fiction Forward, James Thomas and Robert Shapard (2006) affirm that flash fiction fulfills the readers, for it incorporates the same, fundamental elements in standard fiction. They argue that, “The essence of the story exists not in the amount of ink on the page—the length—but in the writer's mind, and subsequently the reader's” (p. 13). As how Pulitzer Prizewinner Robert Olen Butler (2009), a novelist who likewise writes FF, puts it, “Fiction is the art form of human yearning, no matter how long or short that work of fiction is” (p. 102).

Following Wong and Lim's (2014) schematic structure of short stories, it has been found that in general, Filipino FF is comprised of five major rhetorical moves: three of which are obligatory (i.e., Move 1: Establishing a context, Move 2: Indicating a rising action, and Move 3: Delineating the climax), and two were principal or quasi-obligatory (i.e., Move 4: Indicating a falling action, and Move 5: Providing a resolution). Such results also bear similarities with some proposed models of narrative structure of short stories (Butt et al., 2003; Labov, 1972, as cited in Simpson, 2004; McCabe & Bliss, 2003; Nunan, 1999). Likewise, the use of Wong and Lim's move-step analytical framework proved the significance of the occurrence of rhetorical steps in the FF structure, which were mostly obligatory and principal.

Therefore, when reading FF, readers can identify the setting and characters; they can sense the conflict, brace themselves for the climax, and marvel at the denouement and resolution. In FF, a single sentence or two can be sufficient to provide all relevant information about the setting; in most cases, active sentences that incorporate stereotypes and schemas are utilized to vividly detail FF settings and arrest the reader's attention (Thomas & Shapard, 2006). Just like any other fictive writing, at least one character is required in an FF piece. While a regular story plays out character development by showing the reactions of characters to repeated challenges, FF is only limited to capturing a moment or a series of moments; hence, it lacks substantial character development. Some critics would argue that character development is an essential element in a short story or a novel, but not of FF (Ferguson, 2010). Likewise, in FF, conflict or crisis can be deciphered through explicit or, in most cases, subtly implied details. Tension can be built or enacted between two dissimilar characters or even by two opposing worldviews or perspectives (Al-Sharqi & Abbasi, 2015). The ending or resolution of an FF also needs special attention. What makes FF popular is linked to the element of surprise endings, and generally, readers want to be surprised at the ending (Batchelor, 2012). While a traditional story usually proffers its readers with a complete resolution and gives a little room for speculation, FF, in a uniquely profound way, tend to provide suggestive implications that offer variegated answers. In most successful FF, readers tend to hardly guess the closure until after reading the last sentence or the last word; in some instances, however, the ending remains ambiguous. In this case, readers can both feel surprised and disappointed (a delightful mix) with their inability to anticipate the FF writer's resolution, and this unpredictability makes the reading of FF a rewarding experience (Ferguson, 2010; Popek, 2015).

Flash fiction as a literary genre is brief or condensed, yet it is deft and expansive. Barr (2010) argues, “… the point of microfiction [flash fiction] is to have a plot, setting, and a denouement all within the briefest narration. They are not jokes nor extended plays on words … the stories should be able to stand alone” (p. 216). It can be safe to assume then that FF, in a compressed fashion, provides a complete story with a beginning, middle, and end, incorporating a basic setting, a minimal plot, and at least one character; thus, a fragmented story cannot qualify as a flash fiction piece (Batchelor & King, 2014; Gurley, 2015; Ferguson, 2010).

This paper examined the generic structure of flash fiction written by Filipino authors in terms of moves and steps and how such a structure reaffirms or detracts from that of a regular story. It likewise determined the possible rhetorical functions reflected in these communicative moves and steps, and the salient lexical and syntactic features used to perform the said rhetorical functions. In regard to this first objective of the present study, it was found that generally, the FF pieces under consideration incorporate the five communicative moves based on Wong and Lim's (2014) schematic structure of short stories: Move 1- Establishing a context, Move 2- Indicating a rising action, Move 3- Delineating the climax, Move 4-Indicating a falling action, and Move 5- Providing a resolution. A few FF pieces though do not manifest the complete set of these moves in their respective structure, and this can be attributed to the assumption that word limit in flash fiction would tend to suggest only some or a few implicit elements in its storyline. In this case, just like what usually takes place when reading a story, readers have to fill in gaps through inference. Likewise, based on the findings of this study, it is possible that a flash fiction may adapt an unconventional story structure, e.g., it can begin with Move 5 (i.e., 'providing a resolution'), or it can incorporate an additional move such as an 'opener,' which is a short summarizing statement prior to Move 1 (i.e., 'establishing a context').

Furthermore, four steps have been identified as obligatory: 'describing a setting,' 'describing a character,' 'describing a complicating event,' and 'describing effects of a complicating event.' The Filipino FF writers generally prefer to begin a “short” short story by establishing a context, specifically through a description of the place setting, with less emphasis on describing time and weather condition. In some FFs, however, pertinent details describing the place setting are disclosed in other parts of the narrative, not in Move 1. In most of the FFs, 'describing a character' comprises a pivotal constituent step given that the character's name, age, mood, physical attributes, and actions enable writers in conveying background information about a story. Similar to the description of the place setting, important details describing a character, particularly name, age, mood, and physical attributes, would tend to be situated in other parts of the narrative. Worth noting, too, are the two other possible substeps that could be incorporated in Move 1-Step 2 (i.e., 'describing a character'): describing relationship among characters and describing a character's work or profession.

Likewise, based on the analysis of the story structure of FFs, it was revealed that Move 2, which indicates a rising action, is generally articulated in the form of descriptions of complicating events in which difficult or surprising situations are referred. When delineating the climax, the FF writers would less likely stress uncertainty over a situation, but rather, they tend to describe the effects of a complicating event on the character. Consequently, in indicating a falling action, the FFs under study demonstrate a tendency to depict both the immediate results of a decision and the solutions to a complicating event. Lastly, in providing a resolution to a flash fiction, the writers show an inclination to provide a general idea or commentary that accentuates an implicit noble value rather than specifying an explicit moral element.

The move-step analysis conducted in the corpus would prove that Filipino FF adheres to the traditional or regular short story structure. The generic structure of Filipino FF provides a complete story with a beginning, middle, and end; thus, it has the story elements of context, which includes the setting and the character(s); rising action; climax; falling action or denouement; and resolution. With brevity as its unique feature, FF provides minimal yet relevant information about the story's setting; lacks character development, for it just captures a moment or a series of moments, or a sense impression so to speak; often presents the conflict in subtle ways; and offers suggestive implications as regards the story's resolution.

The present study also offers specific pedagogical implications of analyzing the generic structure of flash fiction or “short” short stories. Particularly, teachers can assist students in acquainting themselves with the notably obligatory and principal moves and steps before considering those that are merely optional. It seems crucial then that based on the findings of the study, second language learners should be familiar with the three obligatory moves, namely, Move 1, i.e., 'establishing a context,' Move 2, i.e., 'indicating a rising action,' and Move 3, i.e., 'delineating the climax' and with the two principal moves, namely, Move 4, i.e., 'indicating a falling action' and Move 5, i.e., 'providing a resolution' that are prominent and should be incorporated in all flash fiction. However, the learners should also be aware that some FF pieces may not manifest the complete set of moves in their narrative structure and that other FF works may adapt an unconventional story structure. Based upon the results of the present study, it also seems justifiable to instruct the learners as regards the important role of obligatory and principal rhetorical steps in the generic structure of FF. The obligatory steps include Move 1- Step 1 (i.e., 'describing a setting'), Move 1- Step 2 (i.e., 'describing a character'), Move 2- Step 3 (i.e., 'describing a complicating event'), and Move 3- Step 1 (i.e., 'describing effects of a complicating event'); whereas, the principal steps include Move 3- Step 2 (i.e., 'stressing uncertainty over a situation'), both steps in Move 4 (i.e., 'indicating a solution to a complicating event' and 'describing the immediate results of a decision'), and Move 5- Step 2 (i.e., 'suggesting an implicit moral element').

Future research undertakings may consider exploring other FF works written by Filipino authors in order to validate the findings of the present study. Likewise, future research may build upon the salient findings of the study to determine the degrees of similarities or differences of prominent rhetorical moves and steps across FF pieces in various socio-cultural settings. The present study also recommends than an investigation be done to ascertain how a content-related generic structure analysis of FF pieces can be substantially linked to specific rhetorical functions and their corresponding language resources.

The author wishes to thank Prof. Remedios Z. Miciano, Ph.D. for her informative and constructive comments that substantially helped in the development of this article, and the Philippine Social Science Council (PSSC) and the University of Santo Tomas for the financial assistance.