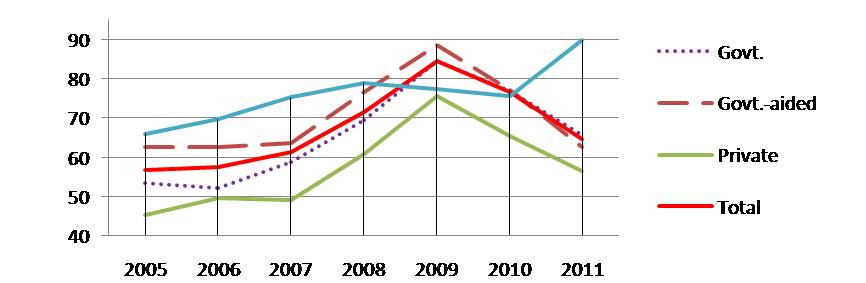

Figure 1. The Pass Percentage of 10th Class during the Years 2005-2011

From a foreign language, English in India has now become a second language (and, of course, the First Language to a considerable people). Many other languages of the world, such as, French, Russian, Portuguese, Italian, etc. are still foreign languages to Indians, but English is not. English is not only taught but also is the medium of instruction in academia. Since it is not the native language, it does not come to the Indians as naturally as it comes to the native speakers. Nor do all have an environment where they can learn English as the native English speakers do. Thus, there are two main points: one, the knowledge of English has become compulsory in the fast changing modern world and second, English, for Indians, is not their native language. It implies that deliberate efforts are needed to develop a command over English language by acquiring skills of reading, writing, listening, and speaking so that Indians can also move with the fast changing world. Present paper is a study of the standard of English language in the schools of Punjab. The statistical analysis and comparisons are based on empirical data, desktop scrutiny of the relevant documents, classroom observations and group and individual interactions. The paper observes the reasons of low standard of English in Punjab and suggests some remedial measures on the basis of the study undertaken.

Over the years, English language has been progressively gaining grounds. Today, it is used as a linking language for wider communication round the globe. It is just “one of the 6912 languages of the world” (Crystal, 2009, p. 58), but it has achieved the status of the queen language of the world, a precious possession. It has become the language of national and international communication. There is no denying the fact, that every person out of four in this world can be reached through English. Today, “there are now something like 250 million people for whom English is the mother tongue or 'first language'. If we add to this, the number of people who have a working knowledge of English as a second or foreign language (many Indians, Africans, Frenchmen, Russians, and so on), we raise the total to about 350 million” (Quick 2), and this number has rapidly increased over the years. In addition to this, English is the official language of nearly 75 countries of the world (Crystal, 2009, p. 54). This importance of English language has been recognized by the Asian countries as well and, thus, it has become the language of administration as well as the medium of instruction in several Asian countries, including India.

English language infiltrated India with the East India Company towards the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth century, where an attempt was made at 'anglicizing' the Indian mind and intellect. In the following years, Lord Macaulay, while implementing his educational policy, made the study of English language compulsory in India. Macaulay was of the opinion that, “English stands pre-eminent among the languages of the West. Whoever knows that the language has ready access to all the vast intellectual wealth which all the wisest nations of the earth have created” (qtd. in Dash & Dash 2007, p. 10). The opinion has an upright relevance even today. Macaulay's educational policy gave Indians not only an easy access to the global world, but also the “encounter between the Eastern and Western thought left a permanent impress on India's cultural history. New movements, religious, social, and cultural also sprang out of this encounter” (Verghese, 1989, p. 3). However, quite late in the 19th century, or probably in 1904, the British government stressed upon the use of mother tongue as a medium of instruction in middle classes and this policy was supported even by the Calcutta University Commission (1917-1919). There was hardly any amendment in the existing educational policies in the second quarter of the twentieth century as this was a period of historical upheavals and many other radical revolutions in India.

During the post-colonial period, English continued to be taught and used in different spheres of life, including education and administration; it even continued to dominate the syllabi of schools, colleges and universities all over India. Various educational commissions and policies though stressed the use of mother tongue and local languages, but the importance of English to the Indian students could not be ignored altogether. In the modern era of science and technology, when English reigns as the language of national and cross-border links, the knowledge of English has become almost a compulsion to be 'the citizen of the 21 century world'.

Any foreign language, including English, is needed for two main purposes – to be able to read the literature available in that language and to be able to communicate with the speakers of that language. There is, however, as Verghese classifies, “a third group of persons, a small minority but perhaps much more important than the other groups that use the English language as a medium of creative exploration and expression of their experience of life” (4). Knowing a ruling language today has become immensely important, especially to enter the global arenas of the world. Probably for this reason, English language has placed itself at the apex of major school and college curriculum across the globe. Therefore, “no one can ignore English, nor globalization, without risking his or her own prospects of growth. If the concept of 'global village' has to have any meaning, the language of communication is bound to be English, at least for now” (Dhanavel, 2012, p. 3).

English, once a foreign language, has now acquired the status of the second language. Other languages like French, Russian, Portuguese, Italian, etc. are still Greek to many. English has become the second language not without a reason, for it is now the medium of instructions not only in academia, but also in politics, law, trade, administration, etc. Since, English is not a native language, it does not come to Indians as naturally as it comes to the native speakers, nor are they the originators of this language as to become well-versed in a jiffy. It could be discerned that, where on one hand, India cannot do away without English, it is not a native language on the other hand. Deliberate efforts are needed to develop a command over English language by acquiring skills of reading, writing, listening, and speaking so as to place Indians in the middle of the changing globe.

As mentioned earlier, during the pre-independence India, English occupied a prominent place in school curriculum. After independence, the University Education Commission (1948) stressed the continuation of English teaching in India at school level. Soon after, the Secondary Education Commission (1952-53) also recognized its importance and advocated in favour of English teaching. The question that still stood, however, was – at what stage should English be introduced in school curriculum? The problem was, nevertheless, solved to a great extent by the Education Commission (1964-66) which introduced the three language formula. The same formula, later on, was also accepted by the National Education Policy (1986) and the Ramamurti Committee (1990) also retained the same. The formula is as follows:

Class I to IV The study of only one language, say regional language or mother tongue, should be compulsory.

Class V to VII The study of two languages (one regional language or mother tongue and Hindi or English) should be compulsory.

Class VIII to X The study of three languages should be compulsory,i.e. Mother Tongue, Hindi and English for non Hindi speakers and the mother tongue, English and any one regional language for Hindi speaking people.

Today, English Language Teaching is being demanded by everyone at the very initial stage of learning. Though almost all commissions, policies, educationists and teaching professionals have recommended a comparatively late introduction of English to the children, there has always been an inclination towards the introduction of English at an early stage by the privately-run English medium public schools. There have been several time to time changes in the curriculum of different state and U.T. Education Boards. At present, most of the state and U.T. boards as well as Central Board of Secondary Education have introduced English from class I itself. In Punjab, the state under study in this paper, English is taught right from the very first class.

Schools in Punjab can be categorized broadly into three types:

All these three types of schools in Punjab are either the government or government-aided schools or run privately by individuals or societies. The Punjab Education Department is in charge of the educational system of the state. Government, Government-Aided, and Private – all types of schools operate in the state. All government schools are affiliated to the Punjab School Education Board (PSEB), Mohali. Both, the government-aided and private schools, are free to get affiliation from any of the three education boards – PSEB, Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE), New Delhi and Council for the Indian School Certificate Examination (CISCE), New Delhi. Among all issues in the sphere of education in Punjab, the standard of English language has received much public attention in the past few years. It has constantly been felt that the average candidates from Punjab lack proficiency in English and generally fail to make it through the interview. They find English as a major stumbling block in their career. It has also been identified that many Punjabis fail to communicate, when they go abroad and hence, an inferiority complex overpowers their will and determination. The gravity of the problem is often highlighted by various privately-run institutions where they teach communication skills in English and help the candidate acquire skills of English language. This is really a strange situation when the Central and State Governments are providing enough funds to maintain and to raise the standard of English at school level. If the educational policies of the government, specifically in English Language Teaching, have not been able to achieve the desired result, there must be some reasons behind it. The present paper is a study and analysis of the standard of English language in Punjab at school level and also an attempt to sort out various reasons for the low standard of English. It also provides suggestions to raise the standard of English in the schools of Punjab.

In this study, investigation was made using a questionnaire containing 30 objective type questions, prepared to study an overall standard of English of school-going students. The questionnaire included all sort of questions relating to various skills of language acquisition. Most of the questions were from the syllabi of English as prescribed by Punjab School Education Board. Some questions were set from English of everyday use (Functional English), which the students of 10th class must be very much familiar with after studying English grammar and composition, as prescribed by the state board, in previous classes. Each question contained one mark and the time allotted was one period (35-40 minutes). The pass marks (score) in each case was kept 10, i.e. 33% of the total marks. The papers were carefully checked, marked and the data was recorded accordingly.

Some information, such as the board results of the previous years was obtained from various sources and was scrutinized for relevant information. Classrooms were observed to get an overall assessment of the target students, more particularly of their psychological state and body language during the test. Interaction was made with the students after the test. During this, the teachers and the heads of the schools were also interacted.

For this study, only the 10 class students were tested. For this test, different Government, Government-aided, and Private schools in different parts of Punjab were randomly selected. The detail of the students tested for their standard of English is as follows:

Total no. of students : 1263

Rural : 513, Urban : 750

Boys : 802, Girls : 461

Government : 421,

Government-aided : 615, Private : 227

Before we go for the results of the analyzed data, it is important to have a look at the overall results of PSEB during last few years. The result of English, in particular, is also equally important in this case. Figure 1 shows the details provided by the Punjab School Education Board, Mohali, which all the targeted schools are affiliated to.

Figure 1. The Pass Percentage of 10th Class during the Years 2005-2011

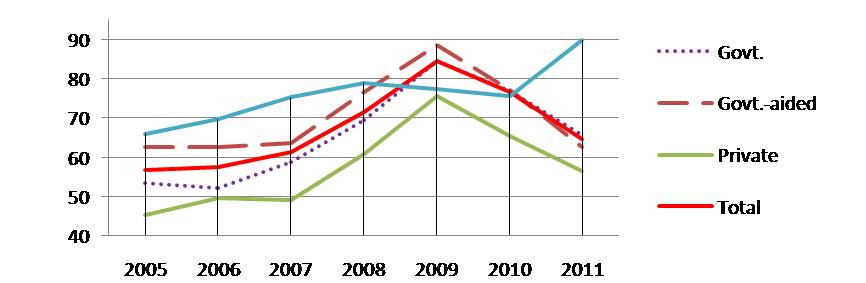

A comparison of the board results during these years with those of English in respective years is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Comparison of PSEB Results (during the Years 2005-2011)

The result of English every year is higher than that of overall board result (except in 2010). The present study, however, has found astonishing results and when compared with the board results, it was found that the standard of English in all types of schools is far below than what it should be according to the pass percentage in the board exams.

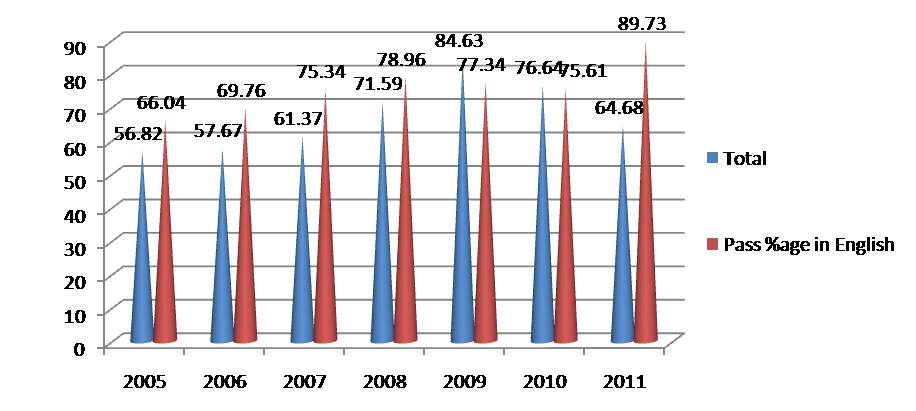

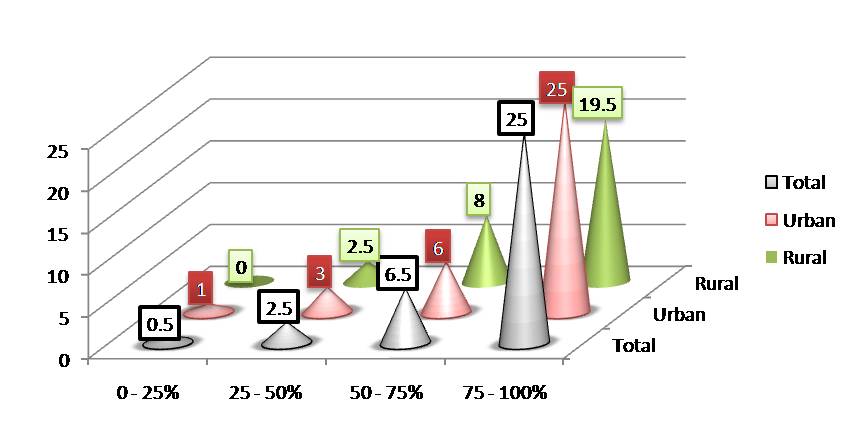

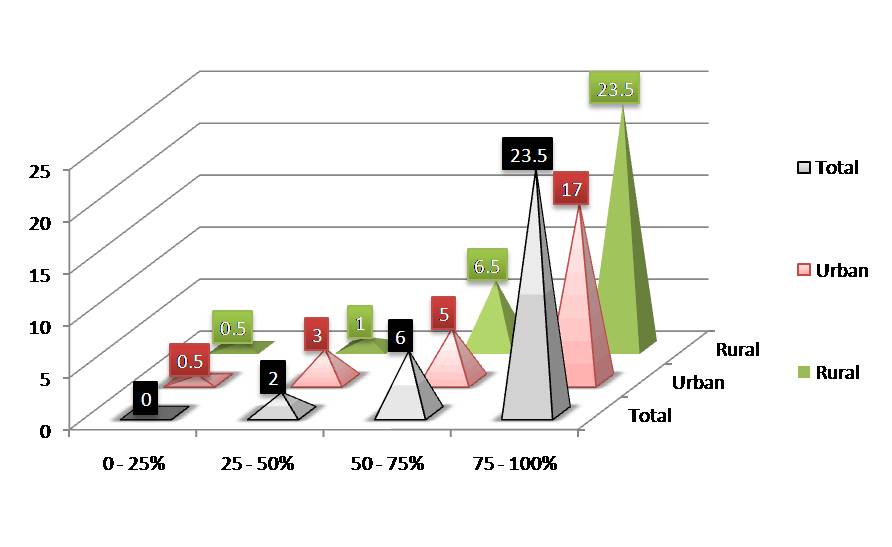

After an analysis of the collected data, a comparison of the standard of English language between different groups of schoolboys is as shown in the following figures: The following bar chart (Figure 3) highlights that a half of the students in rural areas could score only up to 2.5 and in urban their score was just 3. Two third of the students could not get score above 6 in urban and 8 in rural areas. Maximum number of students obtained 0 only. This indicates that there lies a significant difference between the standard of English among the boys in rural and urban areas, but in both the cases, the standard is very low and more than 75% of the students could not even secure pass percentage.

Figure 3. Bar Chart Comparison of all Boys, Rural Boys and Urban Boys

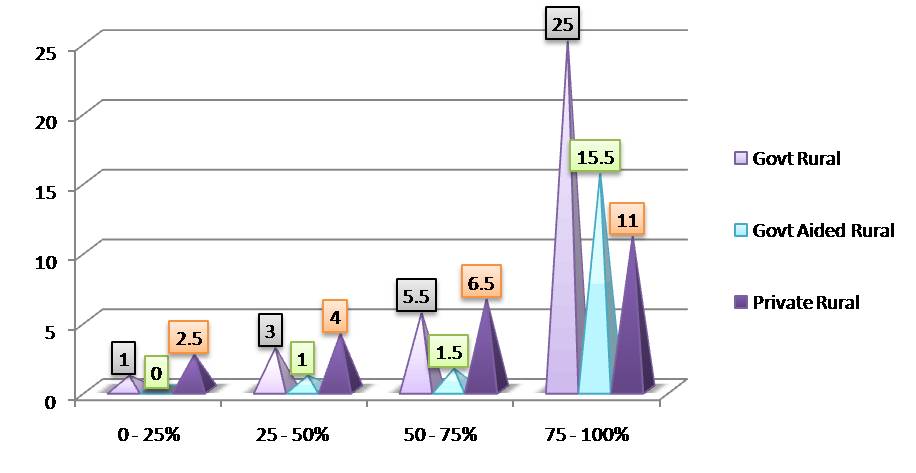

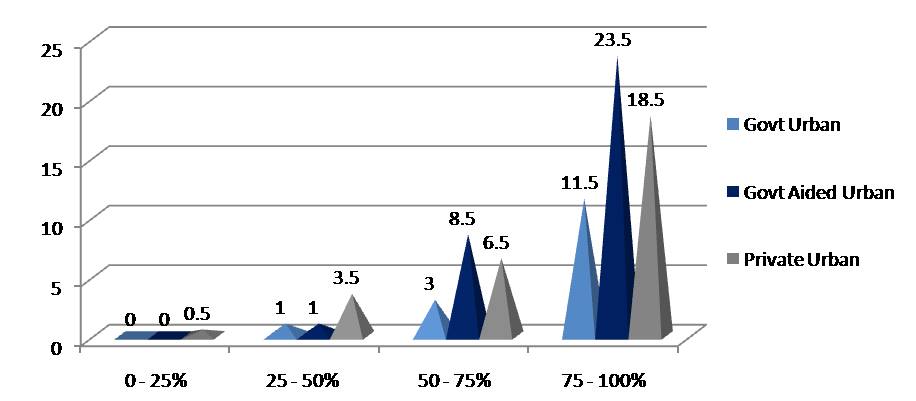

A comparative analysis and its graphic representation of the rural and urban boys from three different types of schools on the basis of their scores is as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Bar Chart Comparison of the Government Rural, Government Aided Rural and Private Rural Schoolboys

Among all groups, more than 75% of the boys could not secure pass percentage. The standard of Governmentaided rural boys was very poor, where more than 75% of them could not get even 2 marks out of 30. A very few boys in Government rural schools secured good marks. The score obtained by maximum number of boys in Government rural and Government-aided rural schools was 0, whereas in Private rural schools it was 3.5. Overall, the performance of the Private rural schoolboys was comparatively better than the others.

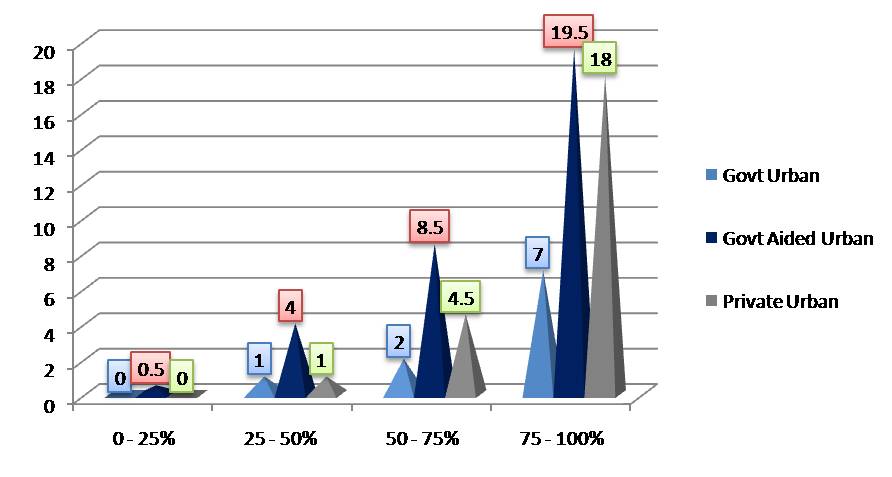

The graph in Figure 5 highlights that among all three groups of boys, maximum boys could obtain 0 only. More than 25% of boys in each group could not secure even 1 mark. Once again, more than 75% of the boys in urban areas too could not pass in the test. The condition in the Government schools was the worst where no student could secure pass marks. A majority of the boys in every group could secure one mark only. The standard of the Government-aided school boys was comparatively higher than the other two categories.

Figure 5. Bar Chart Comparison of the Government Urban, Government Aided Urban and Private Urban Schoolboys

After an analysis of the collected data, a comparison of the standard of English language between different groups of school girls is as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Bar Chart Comparison of all Schoolgirls, Rural Schoolgirls and Urban Schoolgirls

From the graph in Figure 6, this is clear that more than 25% of the girls in urban and more than 50% in rural areas could not secure even 1 mark. More than 75% of the girls in both the cases failed to secure pass marks. Some girls from each group performed well, but their number was countable. The score obtained by maximum number of girls in each group was 0 only. Overall, the standard of English of the girls is very poor both in rural and urban areas.

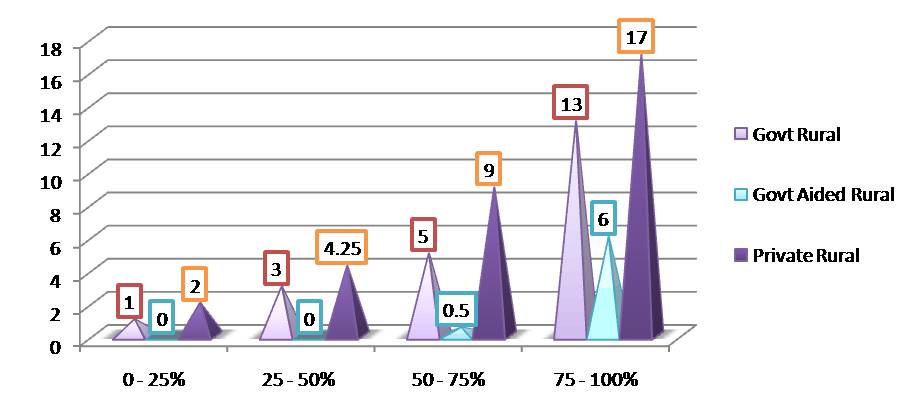

The graph in Figure 7 shows, that more than 75% of the rural girls in all three types of schools failed to score pass marks. The standard of the Government-aided rural school girls was very poor among whom, more than 75% could not even score 1 mark. None of the girl, from Government and Government-aided rural schools could get 50% marks and only a very few girls from the private schools could get above 50% marks. The score obtained by maximum number of girls of Government and Government-aided rural schools was 0, however, in private rural schools it was 2. A comparative analysis and its graphic representation of the rural and urban girls from three different types of schools on the basis of their scores is as in the following graphs.

Figure 7. Bar Chart Comparison of the Government Rural, Government Aided Rural and Private Rural Schoolgirls

On the other hand, as displayed in Figure 8, the standard of girls in Government-aided urban schools was better than that of the other two groups though, here too, half of them failed to secure 1 mark only. More than 25% of the urban girls in each group scored 0 only. More than 75% of them in each group failed to score pass marks. The score obtained by maximum number of girls in all three categories was 0 and no girl, with an exception of a few girls from Government-aided urban schools, could score 50% marks which clearly shows the low standard of English among the urban schoolgirls.

Figure 8. Bar Chart Comparison of the Government Urban, Government Aided Urban and Private Urban Schoolgirls

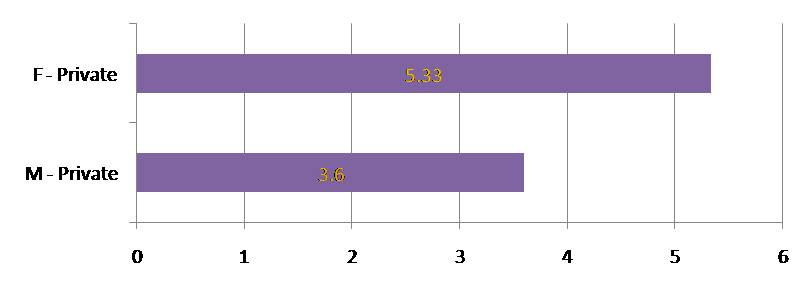

Statistically, there was found no significant difference between the standard of all boys and all girls (p=0.497>0.05), between rural boys and rural girls (p=0.153>0.05), between urban boys and urban girls (p=0.960>0.05), between all Government school boys and all Government school girls (p=0.797>0.05), and between all Government-aided boys and all Governmentaided schoolgirls (p=0.067>0.05). There was, however, a notable difference in the standard of English between all private school boys and all private school girls (p=0.039<0.05). This is shown Figure 9.

Figure 9. Bar Chart Comparison of all Private Schoolboys and all Private Schoolgirls

Below listed are some important observations, which were made during the visits to different schools in different parts of Punjab, from interaction with the students, teachers and heads of the schools, and from the collected data, and its analysis:

The very first reason of the low standard of English in schools of Punjab is the lack of competent teachers. Language teaching, as Neena Dash and M. Dash put in, “is a very difficult task as it involves two aspects, the content element and the skill element. There are not enough competent teachers of English. … the lack of proficiency in English of the teachers at the school stage has added a further dimension to the problem. While, there are specialist teachers in Science. Sanskrit, Hindi, Mathematics, and Social Sciences. English is more often taught by nonspecialist teachers whose own competence in English is questionable” (Dash & Dash, et al., 2007, p. 29). Quite surprisingly, in PSEB affiliated schools in Punjab, the English teachers are not basically the English teachers. Earlier, there was no provision of English Teachers in the recruitment of teachers in Government and Government-aided schools. There was no post for the English teacher. The Social Studies Teachers (S.St. Masters) continued to teach English. It was not weighted at all if the teacher himself/herself had studied English as an elective subject or not. The person who had not studied English was forced to teach English up to matric level. It is only during the last five years or so that the post of English Teachers has been generated in some schools and the recruitments have been made accordingly. In these recruitments, only those candidates who have studied English as an elective subject up to graduation level have been appointed as English Teachers. Their number, however, is very small. In a majority of the schools I visited for this project work, there was no English teacher as such and the S.St. Masters were teaching English.

This new recruitment of English teachers can produce better results in English teaching in future. The selection process on the part of Punjab Government is fairly well, but there are doubts for it to be fine exactly. Before the compulsion of qualifying Teacher's Eligibility Test (TET) exam, several English teachers were recruited in the education department under various schemes. There was no recruitment test and the selections were made purely on merit basis. These were the fair selections – a very good step by the Government – but the selections were not fair. The real potential of the candidates was not evaluated. In the selection of English teachers, there was neither any language based test nor was there any interview to assess their language skills and competency. Consequently, the Education Department could not get efficient English teachers. Moreover, the candidates who are M.A. in English with B.Ed., but without English as an elective subject in their B.A., are also appointed as English teachers. Such candidates are undoubtedly masters of English literature but the basic fundamentals of English language are not very clear to many of them. As a result of this, they fail to teach the same to the high schools students. In the recruitment of teachers in CBSE affiliated schools, English as an elective subject up to graduation remains compulsory. The English teachers, who were interacted with, were far less than to expectations. Many of them showed faulty language skills. Their own pronunciation and the use of language were not up to the mark. In private schools, comparatively a better atmosphere was being provided by the teachers by teaching in English. But the standard of their own English was no more than that of Government school English teachers. It was also observed that this stress on English in private schools was just to attract the parents to get their children admitted to these schools and not to the Government schools. It is perhaps for this reason, that the standard of English, in both the types of schools, remains the same. As far as the use of correct English (among the teachers) is concerned, the condition of private rural schools is worse than the Government rural schools. The reason is that the private schools recruit the teachers not on the basis of their efficiency and fluency rather on that of the salary which they can afford to their teachers. In this case too, the student remains the sufferer.

The first suggestion on the basis of aforementioned observations and reasons is to bring a change in the mode of selection of English teachers in PSEB affiliated schools in Punjab. No doubt, Elective English up to graduation has been made an essential requirement to be an English teacher, but the process of selection needs consideration for a change. A written test should be made compulsory to evaluate the candidates' working knowledge of English. This merit-based selection system should be abolished and selections should be made on the basis of the performance in the written test; at the same time, credits can be given to their academic qualification and their performance in the academia, particularly in English. It should be followed by an interview to check the language proficiency of the candidate. This option, however, is removed by arguing that, it gives a chance for making favour to certain candidates, but this is the only way of checking the language proficiency of would-be teachers. This pattern is followed in the recruitment of teachers in Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) schools and the same can be followed by the Education Department of Punjab Government also. Only good teachers with good communication skills and knowledge of correct English can produce better results.

Secondly, for those in-service teachers who are basically not the English teachers, but teaching English because there is no post of English teacher so far, the department should organize workshops and seminars and personality development programs to train them accordingly. This personality development “should be driven by an analysis of teachers' goals and students' performance; it should involve teachers in the identification of what they need to learn; it should be school based; it should be organized around collaborative problem solving; it should be continuous and adequately supported; it should be information rich; and it should be part of a comprehensive change process” (Clair, 2000). The basic problem is that the English teachers themselves struggle with knowing how to teach English effectively. Their language proficiency and their ways of teaching English at various levels should be assessed. The department should re-shuffle/change the English teachers wherever necessary. New posts should be created and inefficient teachers should be replaced by making new recruitments. Refresher courses in ELT should also be made compulsory for the English teachers.

It was observed that a majority of the students going to PSEB affiliated schools had a weaker social background. The parents who are socially aware prefer to send their children to CBSE or Indian Certificate of Secondary Education (ICSE). At those places where there is no option of CBSE or ICSE, these socially aware people like to send their children to English medium private schools and not to the Government schools. Economic condition of the people, both in rural and urban areas, is equally responsible. The families which are well to do in their financial condition prefer good English medium schools. A majority of the students in Government and Government-aided schools come from lower strata of life. Children from the slum areas are mostly seen in the Government and Governmentaided schools only. They fail to afford the high fees of private schools. A large group of students in PSEB affiliated schools consists of the children from very weak social background who have no environment of English at their homes. This is a considerable reason for the poor standard of English in these schools. The important point, here, however, is that the school-going children of this weaker section of the society cannot be ignored altogether by pointing out to their social and family backgrounds.

According to M. Barrera: “There is a need to examine methods that can be used early in the process of identifying these learners and to provide their teachers with instructionally relevant assessments that can lead to successful remediation of learning problems”. For this, the Government, the Education Board and the Teachers will have to take collective initiatives. A proper research is required in this direction and accordingly should be the syllabi framed, and teaching methods and approaches evolved. For example, as Kunjaban Patel suggests discourse analysis approach when she writes: “… English teaching, in order to be really effective in the Indian setting, must also incorporate in its linguistic content the insights provided by cross-cultural and cross-linguistic discourse analyses” (Patel, 2005, p.149).

In most of the Government and Government-aided schools, there is no suitable environment for teaching English. In such schools, more stress is laid on the regional language and even English is taught through the mother tongue. The language of communication between the teachers and the students even during the period of English is their mother tongue. In private schools, there is considerably better environment of communicating in English, but still the standard is the same, perhaps because of the aforementioned reasons. In all PSEB affiliated schools, even the Government stresses on the use of regional language in all official work which was observed as an excuse by many teachers that Punjabi is thus given more importance and becomes the general language of communication. According to Sharma: “The school must epitomize the culture and foster the natural conditions under which children normally expand into it. The school must be, then, an ideal environment – richer in things, activities, people, and converse – richer than the home, even, or the unselected environment can ordinarily be” (Sharma, 2004, pp. 37-38), and in the case of a suitable environment for English teaching, this is possible only when there are competent teachers to teach English language.

The faulty system of evaluation is another major reason of the low standard of English at school level. English is a compulsory subject in which pass marks are mandatory as failure in English results in withholding the pass certificate. Consequently, the whole attention of the English teachers, as well as of the students, remains focused on getting pass marks and obtaining a pass certificate. This has resulted in a low standard of students' proficiency in English. The marks obtained in English do not clearly indicate the students' achievements in learning language skills. The examination and the evaluation, thus, remain more knowledgeoriented than skill-oriented. On the basis of research and reports, there have been considerable changes in the syllabi of English from time to time, but the system of examination and that of the evaluation has not changed so far. Dash confirms this: “There generally appears a considerable degree of mismatch between stated objectives, prescribed text materials and the systems and techniques of evaluation. In most cases, while syllabi and textbooks have been changed, examinations have remained rigid and unrealistic, thus promising rote learning at the expense of the development of the language skills” (Dash & Dash, 2007, p. 30). The 'English Reader' series, the textbooks of English as prescribed by PSEB, are very good books for the students to learn English. They are well equipped with an ample exercise in applied grammar and composition. These books contain a lot of activities on the part of the students. The problem, however, is that the teachers hardly go with these prescribed exercises at the end of each section. The paper pattern remains the focus of teaching-learning process. The examinations do not evaluate the students on the basis of these exercises and as a result of this, the students as well as the teachers rely more upon the help-books which provide the study material only from the examination point of view. This is quite sure that if the prescribed syllabus and the prescribed exercises in the respective books are sufficient to help the student learn English well, but in most of the cases, it is the incapacity of the teachers to work with the textbooks.

According to Noel: “It can take anywhere from a matter of weeks to six years for a student in a bilingual program to acquire a basic proficiency in English. This depends largely on whether English is introduced slowly or quickly” (Epstein, 1977, p. 25). Today, English is introduced in the very first class, but as the results of this study show, the students are not able to acquire that proficiency in English which they should have after studying this language for about ten years as a compulsory part of their syllabi. Interaction with the teachers revealed some other reasons of the poor standard of English in PSEB schools. Some teachers complain that the quietness and the shyness of the students in English class is a major problem. They argue that most of the students in PSEB schools come from the rural background and belong to the poor section of the society, where (at their homes and in their societies) they have no adequate atmosphere for English speaking. This results in a lack of oral communicative activities in class as well. The teachers say that they are left with no other option than working with the prescribed text and syllabi. This problem, however, is not region specific, but a universal problem for the English teachers. The students' or the learners' anxieties, include “fear of losing face, insecurity, and lack of confidence, all of which slow down progress and impede success in foreign language teaching” (Nimmannit, 1998, p. 37). Some teachers also maintain that the syllabus is too vast for such students. Many teachers blame the primary school teachers for the poor standard of English by stating that they cannot do anything if the base of a student in English is very weak. Most of the teachers also complain that the school teachers, nowadays, have become busier in other activities, ranging from keeping the record of midday meal to working for various other calls on the behalf of the Government from time to time; this has resulted in a decrease in the teaching hours of a teacher. In some schools, the teachers also complained about the problem of controlling and communicating a class comprising of a large number of students. Such problems, however, are not big problems and can easily be resolved, if paid little attention. First requirement for this is an interesting syllabus based on the functional purposes of English and real life interests with cultural representation. This focal point will encourage the students to gain more language competency. “A product-oriented syllabus,” as Geetha Nagaraj describes, “focuses on the skills and knowledge a learner has to get in order to communicate in the language” (Nagaraj, 2002, p. 158). Second, the classroom interaction in English should be encouraged. Creating interest and confidence among the students is the responsibility of the teacher. Interaction in the class should not become a one-way traffic. Teacher-oriented language teaching modes offer little space for students' involvement. They must be avoided by the teacher. Teaching strategies, such as “showing down, enunciating words properly and restating as necessary; providing context clues in the form of gestures, actions, graphs, graphic organizers, and other visuals; drawing on prior knowledge; arranging opportunities for group-work and activity-based learning; and making careful observations of in-class behaviors and accommodating as needed” (Whitsett & Hubbard, 2009, p. 43) should be followed. On the basis of different studies, Whitsett and Hubbard have summarized in the following points as 'Things to Remember':

The education department will have to work in this direction and provide some modern facilities, such as the language labs or other modern audio-visual aids to raise the standard of English in Government and Government-aided schools. The department will also have to keep a rigid check on the working, efficiency and the results, in context of English language of private schools.

The queen's language definitely is the ruling language in the 21st century and is the language of national and international communications now. The South Asian subcontinent is well-apprised with the growing marketability of English language and hence the language is being validated as administrative language too. In India, even the remotest of the areas are scuffling to embrace English as second language. In Punjab, for instance, PSEB affiliated schools are instigating the study of English language in the very first year of their schooling. This region (Punjab) of typical regional accent (Punjab