Figure 1. Model of Intercultural Communicative Competence (Byram, 1997)

It is undeniable that the existence of internationalization has given a great deal of influences within various fields of worldwide nations, namely science, technology, economics, politics, and even education. One of its obvious results is the emergence of intercultural communication and English language has then become as a bridge for cross-cultural communication, thanks to its worldwide lingua franca. For these reasons, Intercultural Communication Competence (ICC) should be more concerned in English Language Teaching (ELT) tertiary contexts. Although ICC in ELT has been long discussed in the previous studies of Vietnamese tertiary contexts, its investigations are revealed differently and separately with regard to its theoretical analysis in this context or its practices in English classrooms. This study aims to gain an indepth understanding on this issue by investigating English teachers' perceptions and practices on ICC in ELT in the context of Vietnamese southern tertiary institutions. The study uses a mixed method, namely a survey questionnaire and interviews to English lecturers from six southern universities in Vietnam. The findings of the study reveal the positive attitudes of English lecturers on ICC in ELT, but certain challenges confronted by their implementations have been highlighted. As a result, some possible measures to enhance ICC engagement in ELT in this context are proposed.

Along with the mainstream of global integration among Southeast Asian countries with worldwide countries, it cannot be denied that Vietnam has constantly undergone considerable changes in education generally and English language teaching particularly, especially the improvement of English teaching and learning, textbooks, as well as evaluation. One noticeable concern discussed recently in this context is integrating culture in English language teaching (Ho, 2011; Ho, 2014; Nguyen, 2007; Nguyen, 2013; Tran & Seepho, 2014). As Byram and Risager (1999, p.58) mention, the role of language teacher has been considered as a “professional mediator between foreign languages and culture” since language and culture is intricately interwoven so that one cannot separate the two without losing the significance of either language or culture (Brown, 1994). Therefore, it is important for language instructors to equip students acquiring intercultural communicative competence (Lázár et al., 2007; Liton & Qaid, 2016; Newton, 2014; Neff & Rucynski, 2013). For these reasons, the role of intercultural communicative competence in English language curriculum cannot be denied.

However, intercultural communication competence has been implied to play a less predominant role in Vietnamese ELT curriculum (Ho, 2011; Ho, 2014; Nguyen 2007; Nguyen, 2013; Tran & Seepho, 2014). This partially leads to the fact that Vietnamese students of English may master English in terms of its grammar and linguistics (Nguyen, 2013), but concentrate less on intercultural communication. Also, many Vietnamese teachers believe in “teaching language first, and introducing culture later” approach discussed by Omaggio (1993). Although this perspective has been gradually changed since Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) has been more concerned in this context, teaching culture, and teaching English language skills has not been integratedly introduced (Tran & Duong, 2015). Further, lacking adequate knowledge and skills in intercultural communication may cause Vietnamese English learners' intercultural communication failure resulted from culture shock and intercultural maladjustment. It is therefore necessary for teachers of English to pay attention to intercultural knowledge and awareness of cultural knowledge to overcome their students' unbiased attitudes towards their own culture and the cultures they learn about.

Some recent research related to ICC in ELT in Vietnam by Ho (2014), Nguyen (2007), and Nguyen (2013) share common points of raising learners' intercultural awareness successfully. While Nguyen (2007) generally suggests a variety of learning and teaching activities integrated in English learning and teaching, to improve Vietnamese current situation of English learning and teaching, Ho (2014) particularly addresses intercultural language learning in English textbooks. Sharing the same concern, Nguyen (2013) examines the extent to which Vietnamese teachers of English in the North of Vietnam integrate in English language teaching, and the results implicate that cultural knowledge is more prioritized than the integration of intercultural competence components. In the context of the South of Vietnam, however, there has been little documentation on intercultural issues. Given the above reasons, the researcher of this paper was motivated to explore an in-depth understanding of English lecturers' perceptions and practices of integrating intercultural communication competence in English language teaching in the Vietnamese southern tertiary contexts, which addresses the following research questions:

The concept of Intercultural Communication Competence (ICC) is acknowledged as the introduction or the revision by different authors of other models of competence. Developed from Chomsky's language competence, it is initially mentioned by Hymes (1972) as communicative competence with regard to grammatical competence and sociolinguistic competence. It is then composed by Canale and Swain (1980) in terms of grammatical, sociolinguistic, and strategic competence. These concepts of competence are grouped into linguistic competence, sociolinguistic competence, and discourse competence by Byram (1997). As mentioned by Byram (1997), ICC is formulated by Intercultural Competence (IC) and Communicative Competence (CC) which are then proposed as five components as presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Model of Intercultural Communicative Competence (Byram, 1997)

The components of ICC can be specifically explained as intercultural attitudes which is explained as curiosity, openness, or readiness to suspend disbelief about other cultures and belief about one's own; intercultural knowledge which shows learning about social groups, products, practices, and processes of interaction; skills of interpreting and relating which are understood as the abilities to identify and explain cultural perspectives and mediate between and function in new cultural contexts; skills of discovering and interacting which are the abilities to acquire new knowledge of a culture and cultural practices and to operate knowledge attitudes and skills under the constraints of real-time communication; and critical cultural awareness which indicates the ability to evaluate critically the perspectives and practices in one's own and other cultures. In other words, intercultural communication competence in English language teaching aims to achieve such components.

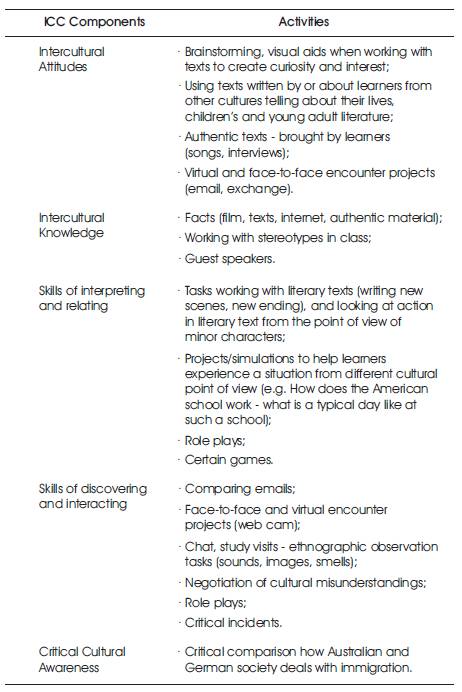

Based on the model of ICC developed by Byram (1997) , Hartmann and Ditfurth (2007) further develop ICC activities in English langauge classrooms. In other words, each particular component of the ICC model is correspondingly developed with specific activities for English language classrooms as summarised in Table 1. Such suggested activities are considered in the practices of the lecturer participants in the current studies combined with those in the empirical studies in the same context.

Table 1. Activities Developing ICC in English Language Classroom

A number of empirical studies have examined integrating intercultural competence through lecturers' perceptions. These studies focused on lecturers in EFL contexts (Eken, 2015; Han & Song, 2011; Ho, 2011; Osman, 2015). In particular, Han and Song's (2011) study employs a questionnaire survey to examine lecturers' cognition of Intercultural Communicative Competence (ICC) in Northeastern Chinese university. The results show that these Chinese lecturers can distinguish between the intercultural approach and the communicative approach to English teaching, but they feel doubtful about the possibility of achieving intercultural skills and integrating foreign language teaching with cultures. Additionally, the results reveal certain challenges faced by these lecturers in terms of limited teaching content of intercultural education, teachers' unfamiliarity with specific target culture aspects, inadequacy of intercultural elements in their teaching materials although these teachers are willing to promote students' ICC in the classroom.

Another significant study on this concern is conducted by Ho (2011) in a tertiary context of Vietnam. The study investigates the presence and status of cultural content in EFL teaching and the effect of intercultural language learning on learners' EFL learning. Being different from the study by Han and Song (2011) with regard to the practice of teaching and learning cultures, the study analyses the underlying assumptions about culture in current EFL textbook units used in this context. The author focuses on the cultural components of the units by using a set of standards for intercultural language learning with regard to raising learners' cultural awareness and engaging the process of learning cultures cognitively, behaviorally, and affectively. The findings reveal lecturers' positive perspectives to fact-oriented approach to cultural teaching. On the other hand, certain limitations to integrating cultural approach to English teaching are revealed as the lecturers' cultural knowledge, the availability of native English speakers, time allowance for culture teaching, as well as the system of education which is not of intercultural education.

Regarding intercultural communication competence from both beliefs and practices, the study by Eken (2015) is carried out with university teachers working at a university in Turkey via a semi-structured interview. The findings indicate that these Turkish lecturers are knowledgeable about ICC, and ready to put their knowledge into practice to raise students' cultural awareness, but certain challenges to their implementation on ICC are shown, namely crowded classes and uninterested students.

Furthermore, the doctoral research project by Osman (2015) is carried out to examine English lecturers' perceptions and implementation of ICC in the preparatory year program at King Saudi University, in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The researcher employed a mixed-method study adapted from the work of Byram (1997). The results indicate a gap between English lecturers' perceptions of ICC objectives and their current practices in the classroom. This gap is arisen from the lack of ICC objectives in the current curriculum.

These previous studies shed light on how English lecturers perceive integrating ICC in EFL tertiary contexts regarding perceptions and implementation. This can be taken as the background into consideration in this study.

The aim of this study is to investigate English lecturers' perceptions of ICC in ELT in tertiary contexts of Vietnam. University teachers were chosen randomly from six Vietnamese southern universities, comprising a hundred and eight lecturer participants. Their teaching experience varied from less than five years to over fifteen years (i.e. 20% for less than five years of teaching, 21% of them teaching from six to ten years, 29% of them teaching between eleven and fourteen years, and 30% of them teaching over 15 years). Most of them have obtained higher education degrees (77% with Masters' degrees and 6% with Doctoral degrees). The majority of these lecturers teach English-major courses, followed by 36% of them teaching both English for major and non-major courses. However, only 10% of them teach cultural-related courses.

To collect data of the participant lecturers' views, an online survey questionnaire and interviews were employed in this study. In particular, the survey questionnaire comprises two main parts, namely English lecturers' perceptions of intercultural communication competence in English language teaching, and English lecturers' perceptions of engaging intercultural communication competence in English language teaching. The study used the researcher-developed questionnaire with both closed and open sections which are based on the discussed literatures because questionnaires are considered as useful tools for collecting data from a large number of respondents (Hinds, 2000). The closed section of the questionnaire follows a five-point Likert scale (Scale 5- strongly agree, 4- agree, 3- moderately agree, 2-disagree, and 1-strongly disagree). The data was gathered and analyzed by the frequency test with SPSS 20.0. Additionally, the interviews was carried out to 10% of lecturer participants, comprising 10 lecturers who are teaching at such six higher institutions. The interviews are formed as semistructured individual interviews. The main advantage of these interviews is to create the opportunity to gain access to what is explained as “inside a person's head” (Cohen & Manion, 1994, p.272). The interview questions asked of the lecturer participants are designed with regard to the lecturers' views and practices of intercultural communication competence in English language teaching in their actual contexts. The answers are then analyzed one by one with regard to the research questions discussed earlier.

English lecturers' perceptions of ICC in ELT of the current study comprises of two parts: (1) English lecturers' perceptions of knowledge of ICC, and (2) English lecturers' perceptions of how ICC can be engaged in English language teaching. In particular, the first part of perceptions show that most of the English lecturer participants (both survey respondents and interviews) claim to hear about the concept intercultural competence (80.4% of survey responses). Additionally, nearly all of these participants agree with ICC as the ability to link one's understanding of other cultures to his communication effectively (96.30%), the ability to acquire new knowledge of other cultures and operate knowledge attitudes and skills under the constraints of different cultures (82.20%) (see Table 2).

Table 2. English Lecturers' Perceptions of Knowledge of ICC

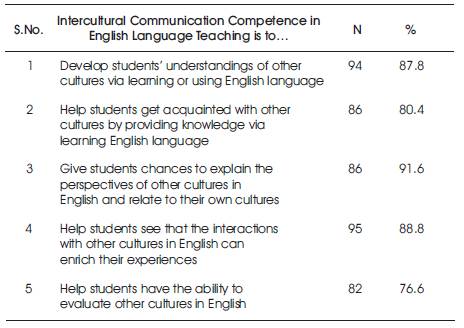

Regarding the second part of perceptions, it is disclosed that most lecturer participants show their highly agreed views on how ICC can be developed in ELT. In particular, nearly all of them agree with developing ICC through developing their understandings of other cultures via learning or using English language (94%), helping students see that the interactions with other cultures in English can enrich their experiences (95%). The same number of respondents (86%) also share their agreement with helping students get acquainted with other cultures by providing knowledge via learning English language, and giving them chances to explain the perspectives of other cultures in English and relate to their own cultures. Although the number of agreed views on developing intercultural communication competence by helping students have ability to evaluate other cultures in English classes is not as high as others' views, this number is not low (82%) (see Table 3).

Table 3. English Lecturers' Perceptions of how ICC can be developed in ELT Teaching

The findings of the current study are in line with the studies by Eken (2015), Ho (2011), and Osman (2015). In particular, English lecturers are knowledgeable about components of intercultural competence in English language teaching. It is clear that the lecturers, by expressing their opinions toward intercultural competence development in English classrooms, show their positive attitudes to students' assistance to achieve ICC. These findings also resemble the conclusion in Eken's (2015) study concerning lecturers' readiness to adapt intercultural competence in their English classrooms.

The second part of the current study investigate English lecturers' engaging ICC in ELT practices. This part include:

In general, nearly all of the lecturer participants (94.4%) are aware of the importance of ICC in ELT. Their views are further explained regarding its strong mutual support to effective language communicative competence, deeper understanding of various aspects of worldwide countries, and limiting cultural aspects' misunderstandings. For example, the interview respondents specifically explained as follows:

“ICC will help learners to be aware of why and how language is used and developed differently and dynamically in order to know what to say and how to say that language appropriately in various contexts.”

“It helps to avoid misunderstanding caused by cultural differences in order to communicate with people from other countries more effectively, as well as have deeper understandings of how people use language in literature.”

“It helps to avoid cultural shock when interacting with people from different countries.”

“It is good for learners' language acquisition…to limit misunderstandings, inappropriate behaviors in different cultural contexts.”

“Students use their new knowledge to identify, explain, and justify different cultural perspectives and to compare and contrast these with clear-cut views from the individual's own culture and other cultures.”

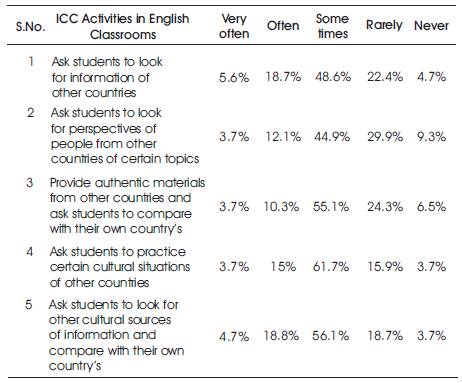

Additionally, the participants of the current study share the frequency of their ICC activities practiced in English classroom. Table 4 indicates that most respondents 'sometimes' and 'rarely' engage so-called ICC activities in English classroom, accounting for from nearly 50% for the former and up to 30% for the latter. However, there is a very small number of lecturer participants who 'very often' (around 5%) and 'often' (between 10% and 19%) implement the listed ICC activities in their classroom. The study results indicate that the current participants experience their insignificant implementation of ICC activities in their English classrooms (See Table 4).

Table 4. Frequency of ICC Activities in English Classrooms (N= 108)

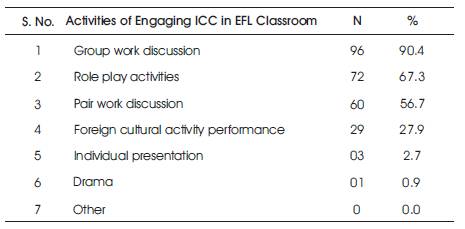

More specifically, the lecturer participants reveal their agreement with the ICC activities engaged in English classrooms, including group-work discussion (90.4%), roleplay activities (67.3%), and pair-work discussion (56.7%).

Other culture-related activities that are not highly agreed, include foreign cultural activity performance (27.9%), individual presentation (2.7%), and drama (0.9%) (See Table 5).

Table 5. Activities of Raising Intercultural Competence in English Classrooms

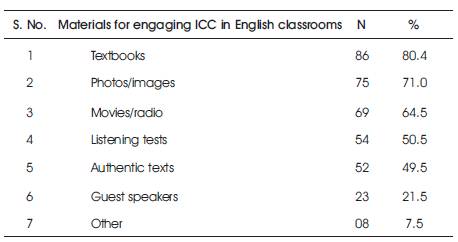

Furthermore, the findings of the current study indicate the lecturer's use of various materials to engage ICC in English classrooms with highly supporting views to textbooks (80.4%), photos/images (71%), and movies/radio (64.5%). The lower number of responses are for listening texts (50.5%), authentic texts (49.5%), guest speakers (21.5%), and others (7.5%) like guest speakers (See Table 6).

Table 6. Use of Materials for Engaging Intercultural Communication Competence in English Classrooms

The current study also reveals the lecturers' actual time distribution for teaching language and culture. Specifically, the lecturer participants indicate that the engagement of teaching cultures in English language teaching is not highly agreed (3.7%). The figures also show that most of the participants agree with 80% of their time distributed to teaching English language compared to 20% of that to cultural teaching. The results, therefore, indicate the disparity with the views of intercultural competence in ELT discussed by previous scholars (e.g. Brown, 1994; Byram & Risager, 1999; Ho, 2011) regarding the intertwined nature of the concept of intercultural communication competence.

Relating to the lecturer participants' evaluation of ICC knowledge, over two thirds (78.6%) of agreed respondents share that evaluating of ICC knowledge account for up to 20% in their English teaching practice, followed by 13.1% of them responding 21-30% of ICC knowledge evaluated, and only 1.9% choosing 31-40% as their ICC knowledge evaluation. The results show that the evaluation of ICC knowledge in ELT is not very focused.

Concerning the lecturer participants' practice of engaging intercultural competence in English classroom, the current study further explores the challenges perceived by these lecturers to helping their students' intercultural competence development. With regard to external challenges, these English lecturers claim limited time to integrate intercultural competence (82.2%), limited teaching resources of cultures (55.1%), limited foreigner environments for communication (55.1%), and limited content of cultures in teaching curriculum (54.2%). Concerning internal factors, although the lower number of responses is for limited knowledge of teaching cultures in English classrooms (42.1%), or lack of training on this area (36.40%), these figures are still higher than the rest. (See Figure 2).

Further challenges to the lecturer participants of the current study explicitly share in the interviews regarding to their time of English language teaching, their current teaching curriculum, their experience of ICC teaching, as well as their students' readiness. The constraints to the implementation of ICC in ELT are explained by some lecturer interview participants as follows:

“I want to engage many intercultural activities in English teaching, but I do not have enough time”.

“The objective of the curriculum clearly mention ICC as the outcome achieved by students, but we do not have many courses on it or it is not included in English course syllabuses.”

“I really want to implement, but I do not know how to engage together with English teaching”.

“I think I often face challenges with my students who are not interested in such ICC activities”.

“My students are really interested in cultural activities, but I cannot spend much time on those activities due to limited time”.

The current study reveals some similar results with the challenges concluded in Ho's (2011) study with regard to time allowance, lecturers' cultural knowledge, and English speaking environment. This could result from the two studies that are in the same nation. Thus, it is understandable why Ho prioritized fact-oriented approach to teaching cultures in English classrooms in Vietnam. Second, like the lecturers in Han and Song's (2011) study, the English lecturers in the current study face challenges from limited teaching content of intercultural education. The third similarity between this study and Osman's (2015) is the limitations of intercultural content in the English teaching curriculum in both contexts.

The current survey with the English lecturers in Vietnamese southern tertiary institutions shows that they are well aware of intercultural communication competence in English language teaching. It can be concluded that the English lecturers in the current study show their readiness to engage intercultural communication competence in their teaching practice in accordance with the current educational reforms to adapt to global integration discussed earlier. The English lecturers in the current study,however, confront certain inhibiting factors to engaging ICC in ELT practices. From the challenges figured out in the current study, several possible suggestions to enhance intercultural competence in EFL teaching are proposed as follows.

First and foremost, it is recommended that, the university administrators should create more favorable conditions to encourage English lecturers to engage intercultural competence in EFL teaching. First, more training workshops in the fields of intercultural communication competence for lecturers should be delivered. Second, redesigning the current teaching curriculum with more integrated content of intercultural communication competence should be taken into consideration. Third, more international standard training programs should be developed properly to attract international students as an effective measure setting English speaking communities for the development of intercultural communication competence. Once these suggestions can be implemented, it is strongly believed that the perceptions and practices of English lecturers' engagement of intercultural communication competence will change positively.

Secondly, the intervention plan for engaging intercultural communication competence in English classrooms should be developed in fact-orientated approaches in association with other forms of intercultural competence integration, namely virtual encounter projects, or ethnographic observation tasks as recommended by Hartmann and Ditfurth (2007) to properly achieve the components of Byram's (1997) ICC model suggested earlier.

Last but not least, further studies in the current context also need to be undertaken to combine with other research instruments, namely classroom obervation, documentation analysis to obtain deeper understanding of the engagement of ICC in EFL teaching. In addition, further comparative studies among various tertiary contexts in Vietnam are strongly recommended to gain deeper insights into the effectiveness of ICC engagement in EFL curriculum.