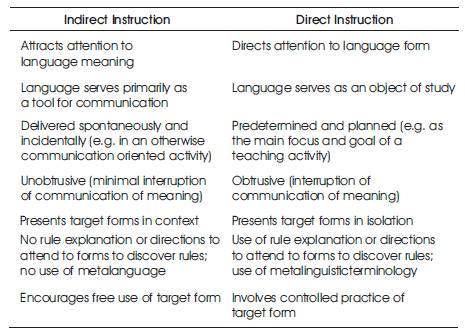

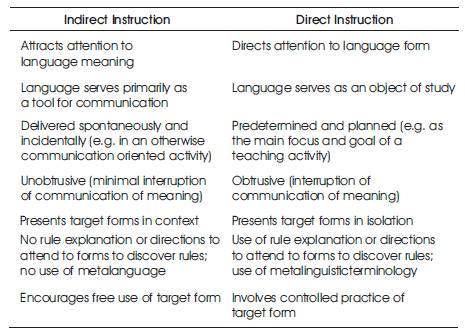

Table 1. Differences between Indirect and Direct Instructions

Second Language Acquisition (SLA), as a sub – discipline in applied linguistics, is rapidly growing and changing (Ellis & Shintani, 2014). As such, it has yielded stirring issues on both naturalistic and instructed settings causing reviews and/or investigations by language researchers. This paper accordingly serves as a humble attempt at critically reviewing the related literature of instructed SLA particularly direct instruction as situated in the landscape of language teaching. Initially, the paper kicks-off with the essentials of direct instruction. It subsequently delves into the importance of such instruction, and this extends to the analysis of notably empirical studies conducted in the 20th century and currently empirical studies in the 21st century. In regards of these, the paper arrives at conclusions, recommendations, and trajectories for future SLA studies.

Second Language Acquisition, henceforth SLA, refers to “the acquisition of a language beyond the native language” (Gass & Selinker, 2008, p.1). It is a complex field of inquiry as it involves interconnected variables (Mendiola, 2016; Ellis, 1985). As this is so, SLA has been faced with never – ending issues and debates since its conception in the late 1950s particularly during the time of Pit Corder in 1967 when he produced his SLA publication entitled, ‘The Significance of Learners' Errors’. Issues in SLA range from the role of the first language (L1), natural route of development, variations in the language learner's contexts, individual learners' differences, role of input, learner processes to the role of formal instruction (Ellis, 1985) which have motivated applied linguists in scrutinizing the world of SLA.

In spite of the above, SLA can be classified only into two: naturalistic and instructed. Naturalistic SLA refers to the acquisition of second language in the actual environment like home where children commonly acquire language while instructed SLA is about acquiring the target language in a classroom setting. Being knowledgeable about the roles of instruction to SLA is valuable for two reasons: First is it assists in developing theoretical understanding as it can shed light on how differences in environmental or naturalistic conditions affect SLA. Second is it aids in developing language pedagogy as it can help to test basic pedagogical assumptions (e.g. whether the orders in which grammatical structures are presented corresponding to the arrangement in which they are learnt) (Ellis, 1985). In this regard, this paper serves as a humble attempt at critically reviewing the related literature of instructed/tutored/classroom SLA particularly direct instruction as situated in the landscape of language teaching. Importantly, this paper primarily aims to:

With these objectives, the author hopes that this critical review of literature will give language teachers, researchers, and practitioners, who are active, enthralled, and even neophyte in the field, a profounder understanding and sense of direct instruction in SLA.

Initially, the paper kicks-off with the essential features of direct instruction. It subsequently delves into the importance of such instruction, and this extends to the analysis of notably empirical studies conducted in the 20th century and currently empirical studies in the 21st century. In regards of these, the paper arrives at conclusions and implications.

As Krashen (2013) explains, “direct or explicit instruction is hypothesized to result in conscious learning, not subconscious acquisition (p.271). Ellis (2010) enlightens that direct instruction has two aims which are to (1) increase learners' implicit knowledge and (2) increase their explicit knowledge of grammar forms. Additionally, it seeks to (3) increase the learner's implicit knowledge of grammar in fluent, but accurate communicative language use. This is believed achievable through increasing first explicit knowledge.

Explicit knowledge is about the rules of language that learners are capable of explaining or verbalizing. An example is the knowledge on forming the past tense of irregular verbs. Implicit knowledge, on the other hand, is intuitive knowledge in that it is a representation of being fluent in the mother tongue. When developed into explicit knowledge, it gets verbalizable. It demonstrates itself through authentic language performance.

Direct instruction can be more understood when it is distinguished from indirect instruction (Ellis, 2008) . Thus, it is important articulating the various features that both have. One notable difference of direct instruction from indirect instruction is its focus on form capturing or interesting the L2 learners' attention on the target language structure. Long 1991, (as cited in Ellis, 2005) uses that term to refer to instruction that engages learners' attention to form while they are primarily focused on message content. In the first, learners are stimulated to develop metalinguistic awareness, while the latter is allowing learners to make inferences on rules without metalinguistic awareness and there is no intention to develop understanding of what is being taught (Ellis, 2010). More than these, direct and indirect focus on form instructions have been contrasted by De Graaff and Housen (2009, p. 737). Table 1 shows the differences between indirect and direct instructions.

Table 1. Differences between Indirect and Direct Instructions

Direct instruction is classifiable into dimensions. The first dimension is deductive and inductive dimension (Ellis, 2010; Ellis, 2008).

Deductive dimension requires metalinguistically explanative type of explicit instruction providing the L2 learners’ explicit elaboration about syntactical structure of the target language. Inductive dimension, on the other hand, is giving the L2 learners the assistance and inputs which they need in order to arrive at an understanding of the syntactical feature they receive. This may be performed in three various forms: consciousness – raising tasks or CR, production exercises, and comprehension tasks. Consciousness – raising tasks are “a pedagogic activity where the learners are provided with L2 data in some form and required to perform some operation on or with it, the purpose of which is to arrive at an explicit understanding of some regularity in the data” (Ellis, 1991, p. 239). The second dimension is a proactive and reactive dimension. The former is based on grammatical syllabus containing structural items to be taught and graded. It includes predetermined instructions to avoid the occurrence of errors by the L2 learners. The latter is attending directly to errors. Its foundation of direct instruction lies on either grammatical syllabus or focused – tasks lessons developed for learners to use a linguistic structure in a context which is communicative (Ellis, 2010).

These two sets of dimension are frequently incorporated in one single lesson (Ellis, 2010). The proactive/reactive dimension functions as the form of explicit instruction and the deductive/inductive dimension serves as a means of identifying the effect of instruction. For instance, proactive deductive direct instruction through metalinguistic explanation of a language structure is succeeded by comprehension tasks which are proactive inductive explicit instruction. Another is deductive reactive direct instruction by explicit correction leading to repetition that is inductive reactive direct instruction. Other combinations are reactive/deductive explicit instruction, and reactive/ inductive explicit instruction (Ellis, 2010).

Ellis and Shintani (2014, Chapter 4) have tabulated the merits and demerits of deductive and inductive direct instruction as shown in Table 2. The table indicates the dissimilarities between the two.

While research designs from descriptive to correlational have enlightened instructed SLA, only experimental studies address the impact of instruction in SLA (Ellis, 2005) . Experimental studies provide more credible findings on the effects of direct instruction in language learning (Mendiola, 2016). Empirical studies have, thus, been chosen for critical review. A valuable question is deemed a need to be satisfied; that is whether direct instruction has a positive effect to SLA or effective.

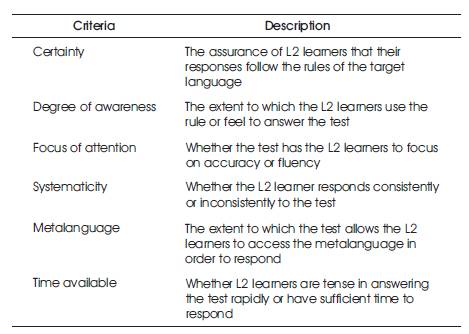

Plenty of research (Ellis, 1985) will reveal the answer to the question in the heading. Measuring the effects of direct instruction should not only refer to the tests that can be appropriately used to measure; however, criteria for opting which measurement tool should be considered as well (Ellis, 2005). They are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Criteria for Selecting an Instrument to Measure Direct Instruction

The effects of direct instruction can be identified through using different instruments as distinguished by Norris and Ortega (2000), and they are if not somehow unlike the ones involved in the dimensions of direct instruction, concrete forms of the dimensions of direct instruction. At the onset, these types of tool to measure the effects of direct instruction are more likely focused on the target form or grammatical structure of the target language. They, however, seem to be indefinite as to which particular language knowledge as explicit or implicit knowledge is being measured. Doughty (2003) asserts that learning is either explicit or implicit.

One is constrained constructed response wherein the L2 learners create the target language form through very controlled linguistic test. Production may be written, such as filling – in the gaps, or correcting sentences containing errors, or oral as recall of isolated sentences. Second is free constructed form, that is, the opposite of the first. Thus, it is not controlled; this is to engage the L2 learners in communicative tasks by which they can produce the target form in meaningful communication. It tests either comprehension of production. Translating an L2 narrative into English, for example, tests comprehension; describing pictures, on the other hand, measures production. Free constructed response is the one which meets the criteria in selecting a test to measure implicit knowledge (Ellis, 2010), while the other three will draw on explicit knowledge. Third are metalinguistic judgments through which the L2 learners analyze the soundness of the target language form being provided. Lastly, selected response is a multiple choice type in which the L2 learners typically select the correct target form in a list of alternatives. Other examples are matching pictures to sentences, choosing from a list of words to complete a sentence, and recognition of words.

It is relatively difficult to create free constructed response tests, whereas it is relatively easy to produce constrained response, metalinguistic, and selected response tests (Ellis, 2010). It is important to note that using these three remaining entails bias towards explicit knowledge of language (Doughty, 2004) on studies which emphasized focus on form direct instruction. Conversely, measuring implicit knowledge is favoured by free – constructed response tests that target meaning not only the form of the target language (Ellis, 2010; Norris & Ortega, 2000). The researcher of this paper contends that using tests that elicit both explicit and implicit knowledge are necessary to overcome biases in treatment and result. Putting more critical attention on this area of measuring direct instruction in SLA is a crevice that requires action.

Notable and classic experimental studies in the 20th century have been considered in this section. They focused on the effects of direction instruction towards the route, rate, and/or success of development in learners' acquisition of the L2. The route of development refers to the general sequence/specific order of acquisition. The rate of development is the speed at which learning takes place, while the success of development is the proficiency level that is achieved. Through morphemes and longitudinal studies on instruction in SLA, they pave ways on increasing theoretical understanding as they can shed light on how differences in naturalistic conditions affect SLA (Ellis, 1985), that is, when the order of language structure instructed to and learned by L2 learners manifested on the results of tests opposed or correspond to the natural order in acquiring linguistic structures.

Lightbrown (1983), Pica (1983) , Sajavaara (1981), Makino (1979), Fathman (1978), and Fathman (1975) (as cited in Ellis, 1985) investigated the acquisition of English morphemes. Their studies focused on the route of development. Lightbrown (1983) had mainly lower intermediate grade 6 pupils, and grade 7 and 8 who were tested through spontaneous speech on picture tasks. Differences from natural order for a number of morphemes such as -ing but disruptions were concluded as only temporary. Pica (1983) had six adults who were native Spanish speakers with mixed ability levels from 18 to 50 years old. They received grammar instruction and communicative language practice, and were tested through hour – long audiotaped conversations. Accordingly, the order of morpheme of instructed group correlated significantly with that of naturalistic group, that of mixed group, and that of natural order by Krashen. Sajavaara (1981) studied adolescents. They received formal direct classroom instruction. Spontaneous elicitation measures were used. In effect, natural morpheme order disturbed – in particular, articles ranked lower. On the other hand, no significant difference between that of morpheme order subjects and the natural order reported by Krashen (1977) was revealed by Makino (1979) who studied mixed-ability-level EFL learners who were 777 adolescents and children receiving formal classroom instruction just like that of Sajavaara (1981). The difference of the result perhaps could be associated with the type of test used. Makino (1979) utilized written short answer test, while Sajavaara (1981) used spontaneous elicitation. The effects vary and they seem dependent on the type of test measuring the language acquisition. Another case in point is the study of Fathman (1978) who also used adolescents with mixed ability levels. They received grammar lessons, drills, and controlled dialogues. Through oral production test, the L2 learners resulted into 'difficulty order' of morphemes which significantly correlated with the order evident in speech of adolescent ESL learners who were not receiving instruction in United States. Similarly, Fathman (1975) used oral production test to 260 children ESL learners (elementary and intermediate) aged 6-15 years old with mixed first language backgrounds. Findings showed different result, that is, the morpheme orders of pupils who received instructions significantly correlated with those pupils who did not receive instruction. It may be valid to claim that this result differs from that of Pica (1983), Sajavaara (1981), and Fathman (1978) since younger participants became the subjects of study of Fathman (1975). Thus, age aside from the type of test appears to affect the findings.

Conversely, longitudinal experimental studies of Ellis (1984), and Felix (1981) (as cited in Ellis, 1985) prove the route of second language acquisition is not affected by direct instruction. Overall, the results showed that the instruction did not impact the route of development of subjects as experimental and control groups were compared and analysed. Ellis (1984) had British ESL beginners as subjects aged 10 to 13 years of age with Punjabi and Portuguese as their L1. Communicative classroom speech which focused on meaning served as the source of measurement. As a result, the overall developmental route was found the same as naturalistic SLA, and minor differences were a result of distorted input. Felix (1981) had recorded classroom speech audio with German EFL beginners. These L2 learners either selected any structure randomly from repertoire either or produced utterances following same rules as naturalistic SLA.

Ellis has resisted through closed examination of different studies on morphemes that formal grammar instruction does not affect the natural route of development or the order of development of grammatical features (Ellis, 2005). Similarly, longitudinal researches on instructed SLA do not prove a great role to play in the route of development among L2 learners.

What may be questioned on these empirical undertakings may have been the type of knowledge being measured. Lightbrown (1983), Pica (1983), Sajavaara (1981), Makino (1979), Fathman (1978), and Fathman (1975) may have failed to specify or classify whether explicit or implicit knowledge on the target language structure did the L2 learners acquire. The balance between the two may be absent as both types of language knowledge are subjects of ambiguities; so, this suggests that there had been an existing dearth of unbiased empirical studies on the area of route of development which needed gap – filling. If this is not so, is balance between explicit and implicit knowledge applicable only for the rate and/or success of development?

Most of the studies found on the rate and success of development stressed relative utility, that is, the overall effect of formal instruction in ESL and EFL classes. It further means that the effects relate with direct instruction. These studies show positive effect of instruction, uncertain findings, and no effects of instruction. Tests used for measuring acquisition were discrete-point and integrative. One may analyze that discrete-point tests are metalinguistic judgment, constrained constructed response, and selected response tests, while integrative tests are free constructed response tests. Carroll (1967), Chihara and Oller (1978), Briere (1978), Krashen, et al. (1978) (as cited in Ellis, 1985) reported the positive effects of instruction with exposure. Carroll (1967) examined adults from all proficiency levels and whose L1 was English. Based on the result of integrative test, both instruction and exposure help, but exposure helps most. Chihara and Oller (1978) also studied students from all proficiency levels but Japanese adult learners. Through discrete point test and integrative test, results revealed that instruction helps, but exposure does not. Briere (1978) and Krashen with his colleagues have the same result. Briere (1978) had children whose L1 was Indian learning Spanish as a second language in Mexico. Consequently, both instruction and exposure help, but exposure helps most. Krashen, et al. (1978) had adults with mixed first languages having all proficiency levels. Using discrete-point and integrative tests, both instruction and exposure help, but exposure helps most. Both studies, however, differ in terms of the types of subjects. The study of Krashen, Seliger, and Hartnett (1974), Krashen and Seliger (1976), and Fathman (1976) provide results that instruction is helpful, but the evidences are insufficient or ambiguous. All the first three used adult learners with mixed first languages with all proficiency backgrounds, but only Fathman (1976) had children. There must be other factors that affected the results such as the length of exposure to direct instruction in the classroom. It is surprising to find out that the study of Upshur (1968) and Mason (1971) report that there is no advantage of instruction and exposure. Upshur (1968) had adults with mixed first languages and from intermediate and advanced levels, whereas Fathman (1975) had children with mixed first languages also and from all proficiency levels. The first took discrete – point test while the latter took integrative test. One possible cause may be the variety of L1 where the subjects were possessing. This could be an area that needs investigation. As there are probably studies that have been conducted on this void, further researchers may be deemed necessary.

More SLA studies on direct instruction had different foci. Pienemann (1985, 1989) had teachability hypothesis that effective instruction needs to target features that lie within the developmental stage next to that which the learner has already reached. L2 learners were exposed to an input flood of question forms at Stages 4 and 5. It was predicted that learners at Stage 3 would be better placed to benefit from this than learners at Stage 2. By advancing to Stage 3, learners benefited most from the instruction. This proves Ellis' conclusion that direct instruction does not alter the natural route of acquisition, but it enables learners to progress more rapidly along the natural route. Fotos (1993, 1994) had grammar discovery tasks aimed at developing metalinguistic knowledge of L2 learners. Instruction was measured by the following: learners' ability to judge the grammaticality of sentences; learners' ability to subsequently notice the grammatical features in input; and the magnitude of the effect of instruction when assessed through meta-linguistic judgment (Norris & Ortega, 2000). Tests were less selected response or constrained constructed response, but more free constructed response. Findings showed ambiguity that the extent to which instruction can help learners to an explicit understanding of grammatical structures remains uncertain as indeed does the value of instruction directed at this type of L2 knowledge. On the other hand, Fotos and Ellis (1991) utilized didactic and discovery based approaches. They found that both were effective in promoting understanding of a grammatical rule as measured by a grammaticality judgment test. This might be so because the students in this study were unfamiliar with working in groups, as was required by the discovery option by Fotos and Ellis (1991). Ellis (1991) used consciousness-raising tasks. CR tasks were found to have their limitations as they do not demonstrate empirical results. But through it, explicit knowledge of the L2 facilitates the acquisition of implicit knowledge. VanPatten (1996) investigated on the relative effectiveness of structured input and production practice. Learners who received input-processing instruction outperformed those receiving traditional instruction on comprehension post-tests. However, this may be owed more to the structured input component than to the explicit instruction as VanPatten (1996) claims. On the other hand, Harley (1989) , Lyster and Ranta (1997), and Muranoi (2000) testify the effectiveness of functional grammar teaching. The success of the instruction was derived from both test-like and more communicative performance; however, it does not appear to be dependent on the choice of target form. Hawkins and Towell (1996) used form-focused instruction. It was revealed likely to be more effective if the targeted feature is simple and easily-explained. Lastly, Truscott (1999) had corrective feedback as mode of direct instruction. Negatively, correcting learners' errors revealed no effect on learners' acquisition of new L2 forms.

Observably, these empirical studies have different results depending on the type of direct instruction used. The question now is which is the best way to prove the effect of direct instruction to SLA?

The 21st century offers more experimental studies. It has become apparent that explicit instruction for almost or more than 20 years has a positive effect on second language learning and performance (Ricketts, & Ehrensberger – Dow, 2007). These SLA studies focused on presentation of rules, exposure to relevant input, metalinguistic awareness, feedback, and opportunities for practice among others. The studies in this section are so far conducted with most L2 learners who were learning English as a foreign language.

Macaro and Masterman (2006) probed the effect of intensive direct grammar instruction (focus on form) on grammatical knowledge and writing competence among freshman students of French as L2. A group of learners received explicit instruction in French as L2 while another group did not receive any intervention. Discrete-point grammar test was used to measure their acquisition of French relative pronouns, verbs/tenses/aspect, relative clauses, agreement and prepositions. The learners took a pre-test (for both groups), interim test taken one week after the instruction (for the experimental group only), and post test on the 12th week (for both groups). The tests were in four styles: grammar judgement, error correction with rule explanation, translation that are discrete – point tests, and narrative composition that is a production task. Accordingly, the experimental group improved significantly between interim and post-tests and not between pre and interim tests in terms of spotting and correcting errors, and explaining their corrections. The control group did not attain significant improvement. Both groups improved significantly in their narrative compositions, but the experimental group did not gain development in terms of grammar accuracy between pre and interim tests. The number of participants did not really affect the results. Moreover, the first group did not outperform the second group in terms of translations tasks. In effect, the intensive grammar direct instruction was found as insufficient variable to bring about a significant improvement in the learners' grammatical knowledge since there was no extent to which overall judgments can be made between the two groups.

Relating with the last statement, the result of the study cannot be generalized as effective in developing L2 learners' interlanguage. One may suspect that the number of subjects affected the findings while the nature of using direct instruction is actually grammar intervention. Another might be Macaro and Masterman's lack of control over the quality and quantity of direct instruction for the learners. Their individual differences could also be a factor.

A similar result supports Macaro and Masterman's (2006) experimental inquiry. Nazari (2013) investigated the effects of both direct and indirect instruction on learners' ability to learn grammar and apply it in their writing. Unlike the study of Macaro and Masterman, Nazari focused on English as L2. Two intact classes with 30 students, that is, 60 female Iranian adult learners were used for teaching the present perfect by various methods of instruction. Through direct instruction, learners got exposed on direct explanation of the rule on the part of the teacher, having students work individually or in pairs composing sentences, using the sentences in order to extract and explain the use of rules, having the learners do the related exercises taken from Grammar in use, and translation. Indirect instruction included schema building (showing the grammar in use, not talking about it) by making examples, having students watch a related film answering the questions in such a way that they would have to use the targeted, and providing a text with highlighted forms of the intended grammatical structure. This lasted for 10 sessions. Given a teacher – made grammar test to check the learners' achievement, the group that received direct instruction outperformed the group that had indirect instruction. Direct instruction had a better effect in enhancing the L2 learners' grammatical knowledge (Nazari, 2013).

At a similar note, Finger and Vasquez's (2010) study had 17 Brazilians learning English in a university received direct instruction on present perfect and simple past as well. They were tested twice through comprehension and production tests as pre and post-tests during a three –week interval. The experimental group was actually tested in terms of form and function. This group performed better than the control group as the first group got higher scores in the comprehension test on present perfect and simple past. This is understood as attributed to the fact that explicit instruction is direct and affects a learner's perception of the target linguistic item in the sense that they used it frequently. Thus, the positive result linked with direct grammar instruction. The control group that did not receive direct instruction, however, showed significant improvement as a result of the production test in simple past only and not present perfect. This is not necessarily based on direct instruction, but on first language interference (Finger & Vasquez, 2010). Results indicated that through direct instruction, the learners gained an overall improvement.

Given this positive result, can one declare that the findings have been conclusive to the extent that no further inquiries on direct instruction in SLA are to be explored? The amount of target input may be tested in order to obtain more comprehensive results. More testing may be deemed necessary to reveal whether the L2 learners achieved long –term improvement.

On the other hand, Gardaoui and Farouk (2015) compared the relative effectiveness of direct instruction before input enhancement on English tense and aspect, and input enhancement alone with 38 Algerian young adult ELF learners in the tertiary level. All participants participated in a pre-test and post-test that was varied in formats: (1) a grammaticality judgment task, (2) a written gap-filling task; and (3) a picture description task.

The instruction for the experimental group included form – focused macro options: (i) input flood, (ii) textual enhancement operationalized by combination of bold and color, and (iii) rule – oriented. The control group comprised of activities where learners engaged with language receptively, that is, language input in the form of listening and reading tasks. Results showed that the group which received direct instruction prior to the input enhancement exceeded the performance of the other group which did not receive direct instruction. The first though did not reveal statistically significant learning improvements. As measured by the grammaticality judgment post-test, input-based L2 instruction alone does not lead to improved performance on tasks involving the comprehension of English tense and aspect. A direct instruction incorporating input-based-instructional treatment cannot be held responsible for enabling L2 learners to comprehend and to produce the target structure more effectively than inputonly. The result, then, implies that coalescing direct and indirect grammar instructions is a better option (Gardaoui & Farouk, 2015).

Results according to Nazari (2013), and Gardaoui and Farouk (2015) could be attributed to several reasons: learners being habituated to direct instruction or direct instruction without implicit conditions; the type of grammar test used (multiple choice, contextualized, and sentence making); the aims of the university's syllabus enabling the students to identify the grammatical rules, and to use them correctly, and focusing on grammatical forms and the usage of grammatical features without emphasizing grammatical features in meaning–based contexts (Gardaoui & Farouk, 2015). Moreover, L2 learners' individual differences are a factor. The participants' characteristics, such as motivation, positive attitude, and perseverance to learn affected their success. Considering these factors in mind could make another SLA research more carefully planned and thoroughly done.

Tavakoli, Dastjerdi, and Esteki, (2011) determined the effects of direct strategy instruction on L2 oral production with regard to accuracy, fluency, and complexity of 40 male intermediate EFL learners. Being an experimental study, communication strategy instruction was the independent variable. Learners were taught of four communication strategies: circumlocution, approximation, all-purpose words, and lexicalized fillers. Learner's oral proficiency, that was the dependent variable, was assessed using analytic measures of accuracy, fluency, and complexity. Twenty each in number, the experimental group and control group had eight sessions. The first was made aware of the various strategies to compensate certain communication difficulties through the teacher's direct instructions, whereas the latter received no special treatment. It only underwent normal routine class procedure. Using interview as post-test that was transcribed, examined, and coded in terms of accuracy, fluency, and complexity the study revealed that direct strategy instruction aids oral performance and the experimental group achieved a higher level of accuracy, fluency, and complexity. Explicit teaching of communication strategies may have a positive effect on the learners' strategic competence.

If Tavakoli, Dastjerdi, and Esteki's (2011) conclusion is so, incorporating communication strategies into the English language curricula, then, is important. Some may contend though that communication strategies have been observed if never taught, implicitly to ESL/ELF learners for example in the Philippines, Singapore, Japan, Korea, China, and so on. A similar study focusing on the effects of direct instruction to the oral communication skills of Sudanese high school EFL learners was that of Nasr (2015). He used teacher's questionnaire and learner's questionnaire. Contrary to the positive result that Tavakoli, Dastjerdi, and Esteki (2011) had reported, direct grammar instruction made a negative effect on the learners' communication skills and it exposed them to the least possible amount of linguistic structures to acquire. Coming from the words of Nasr, (2015, p. 155) , “Explicit grammar instruction impedes fluency and oral communication in general, on the other hand, it exposes EFL learners' to a little amount of language that presented by the teacher”.

One question to arise in scrutinizing why it had a negative effect towards the L2 learners perhaps is the amount of time the English language teacher(s) devoted for each opportunity of providing direct instruction. The time and the days of teaching the Sudanese learners, however, were not mentioned in their experimental study. If the amount of direct instruction covers the entire class time of the L2 learners, acquiring the target structures may suffer; thus, leading to less chance of acquiring the language. Or should the learners be exposed more on grammar exercises and communicative activities that these activities should play more amount of time instead of direct instruction.

On the oral grammatical performance of teacher candidates, Wu's (2007) dissertation that employed a pretest- post-test experimental design reports that the randomly assigned teacher participants (average age of 19 years old) who were directly taught on English conditionals for five sessions via EEGI (i.e. Explicit Experienced Grammar Instruction) improved their oral accuracy. The test used was pre-test-post-test oral interview. Using statistical regression, the degree of accuracy was around 37% after direct instruction that Wu (2007) related with the experimental group being immersed in several communicative meaning – based activities to practice English conditionals. On the other hand, 60% development was linked with EEGI. The remaining 40% might be based on explanatory variables different from EEGI: learner's psychological aspects, namely aptitude, cognition, learning styles, and motivation, and social elements such as learning environment that both represent learner differences (Wu, 2007). Another was the error of measurement which is unavoidable in all type of research inquiry. These variables were not explored whether valid or invalid indicators carrying the puzzling 40%. Explicit grammar instruction in English conditional sentences can explain the reasons why the experimental group outperformed the control group.

Direct instruction also affects the implicit and explicit knowledge of L2 learners (Nezakat – Alhossaini, Youhanaee, & Moinzadeh, 2014). The study of Nezakat – Alhossaini, Youhanaee, and Moinzadeh (2014) explored the impact of direct instruction on the acquisition of English passive objective relative clauses. Their experimental group underwent four sessions of direct instruction while the other group remained on its common routine in the writing class. Two separate tests of explicit and implicit knowledge used varied: an offline test of metalinguistic knowledge (an error correction task) and two online speed tests of implicit knowledge (a self-paced-reading task and a stop-making sense task). Randomly divided into experimental and control groups, intermediate EFL learners, male and female, participated as the first group. The second and control group consisted of PhD students of TEFL with an average of 10 years studying English as a foreign language, but never lived in an English speaking country. A pre-test, a post-test, and a delayed post-test were administered to both. Considering the effect of direct instruction to explicit knowledge, both groups accordingly made similar performances in the pre-test; however, the experimental group outperformed the other group in the immediate post-test by producing the accurate form of relative clauses after direct instruction. In the offline posttest, there was no significant difference found between the two groups' performance. Direct instruction also improved the learners' implicit knowledge. The experimental group decreased reading time that was indicated by the similar performances of the control group. The experimental group showed a faster automaticity in their delayed posttest than the other group. The rate of progress of the L2 learners can speed in acquiring complex grammatical structures through direct instruction. However, one may view that this finding is no longer new. What more can direct instruction bring about to the EFL learners? What about online direct instruction in acquiring a second or foreign language?

Tamayo (2010) analyzed the role and effect of explicit English grammar instruction focusing on form. Grammar instruction took five hours every week, one hour per day. Randomly selected, ten 17 to18 year old L2 learners (advanced level) who were Spanish, participated in an oral interview. Then, they identified the correct sentence they had previously produced in the oral interview in studentspecific tests that consist of ten pairs of sentences. Each pair had a correct sentence and an incorrect option added. The learners analyzed their choices by providing either explicit or implicit explanations. Accordingly, most of the learners selected the correct sentence and explained their correct choice in the student-specific tests. They preferred explaining most of the structures through explicit knowledge. They used implicit knowledge only when they lacked the technical terms to explain the phenomenon. Tamayo (2010) claims that direct grammar instruction that is gradually developed through practice in the process of learning has an effect in SLA. Moreover, it could aid the learners in making them feel more certain and self - confident on the utterances that they produced. Form – focused direct instruction raises awareness about language accuracy.

What may be missing in Tamayo's study is the fact, the language also has other dimensions such as meaning and function. While this may be rare in tutored SLA settings, meaning – based direct grammar instruction may offer the chance for learners to use the target language which in turn may be viewed as a void that needs research.

Explored on the qualitative effect of direct instruction as intervention on Korean learners' perceptions on writing and editing skills at the sentence level (i.e. Complete Sentence, Verb Tense, Simple Sentence, Compound Sentence, and Complex Sentence), Wang G.H. and Wang S. (2014) had intermediate-level freshman English learners accomplish a pre-intervention writing assignment before receiving sentence grammar instruction, and a similar but slightly different post-intervention assignment after receiving the instruction. A set of workbooks which the students read and studied for homework over five days was provided as a form of grammar instruction to the learners. This alone was the grammar instruction provided. After submitting the post-intervention writing assignment, the learners answered an online survey anonymously to reflect on their experience of the overall task. The results of the survey point to a positive impact of the direct instruction on their perceptions of their writing and editing abilities. This entails that it is actually likely to deliver direct grammar instruction in written mode without interventions coming from the teacher's involvement.

While Wang G.H. and Wang S., (2014) conclude such positive effect, they themselves admitted that generalizability of their findings was weak given that it lacked a control group. The dearth of participants and scope may be needed to investigate more on the connection between direct instruction and writing performance. In addition, they might have missed that perceptions just like reflections serve as data for triangulating other primary data. Perceptions are also difficult to measure. This study is significant for raising the issue that direct grammar instruction delivered in the form of workbooks could have a beneficial role in foreign language writing pedagogy. This may be a good area for research as a little amount of studies are being conducted in second language writing.

As stated earlier, the field of SLA is dynamic and growing and doubtlessly there is still a continuing need for an updated survey. This statement may sound motherly and conventional, but the author of this literature review sees no other insightful way but views SLA as a field of research that has not yet reached its final conclusiveness. Results from various researches in the 20th and 21st century vary because it is given that SLA is a complex process, involving many interrelated factors (Ellis, 1985). These factors as explicitly and implicitly described in the two sections above ranging from the types of tests used, types of L2 learners, proficiency levels, L1 backgrounds, grammatical structure being instructed, the amount of exposure, the type of direct instruction used, etc. Other factors which might have affected SLA may be more that what have been analyzed. To re-emphasize, no SLA research is perfect as far as searching for the final day to be conclusive on the effects of direct instruction to SLA; therefore, more research is required to come to the point of certainty (Nazari, 2013). To prove that these studies conform to the qualities of empirical research, researchers of today may conduct related studies. They should focus more on pronunciation, vocabulary, discourse structure, and functions in any of the four language skills. Overall, it is thus essential to note that these studies on directed instruction in SLA regardless of their procedure and results offer applied linguists and language specialists alike sound insights in investigating more on SLA, and in teaching and learning languages.

The author would like to thank, first the Lord Almighty, for his wisdom and guidance, second his family, for their love and support, third his professor, Dr. Cecilia M. Mendiola of PNU, for her guidance in writing this critical review.