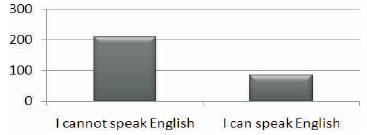

Figure 1. Students' Beliefs About Whether they can or cannot Speak English

The saying 'I can understand English but I can't speak' is so commonly used by Turkish people that it would be fair to state that not being able to speak English has almost become a syndrome in society. This study delves into the causes of this syndrome. In two state high schools, 293 high school students filled out a questionnaire including Likert-type items about the possible causes of this syndrome, and an open-ended question aiming to reveal their suggestions on how they can improve their speaking skills. The analysis of the quantitative data was done by means of Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 23, and the responses to the open-ended question were analyzed through content analysis. According to the results, it is commonly believed that they cannot speak English because of the focus on grammar rules in English lessons, differences between English and Turkish, lack of experience abroad, limited speaking practice opportunities outside the classroom, feeling anxious while speaking English, use of mother tongue by the teacher and the course books which do not include colloquial English. Therefore, some of the participants suggested having communication driven lessons and engaging in out of class speaking practice activities as ways of improving their speaking skills. It is hoped that such studies will help better understand the sources of failure in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) speaking,and begin to solve this problem more effectively.

In Turkey, English is the most commonly studied foreign language used as an instrumental language mainly for international business and tourism; additionally, it symbolizes modernization and elitism (Doğançay- Aktuna, 1998). Although English has no official status in Turkey, the country is under the influence of trends affected by the spread of English as in many other contexts(Arık & Arık, 2014;Doğançay-Aktuna & Kızıltepe, 2005) . In the report 'Turkey National Needs Assessment of State School English Language Teaching' published by the Economic Policy Research Foundation of Turkey (TEPAV) and the British Council (2014), it is also emphasized that English is the major language for international communication in the country and is a necessity for higher salaries and enhanced career opportunities. In addition, the report indicates that knowing English has an influence even on Turkey's long term economic growth potential, and it can lower the transaction costs of gathering information, establishing contacts and carrying out negotiations. Also, it is believed in Turkey that people who can speak English are more educated and thus superior to other people who cannot (Küçük, 2011).

However, as argued by some researchers, an adequate level of English proficiency cannot be attained in the country in spite of all the efforts and investments (Işık, 2008; Kırkgöz, 2008;Aydemir, 2007;Çelebi, 2006). The findings and arguments of these researchers were proven by the statistics provided by EF English Proficiency Index (EF EPI) (2015) which ranks Turkey as the 50th country among 70 countries in the "very low proficiency" category. What is even worse is that Turkish EFL learners generally indicate that they can understand English but cannot express themselves verbally in English(Koşar & Bedir, 2014) . On the other hand, Dinçer and Yeşilyurt (2013) point out that the problem is not unique to Turkey by arguing that the situation is similar in many Asian countries, such as Japan and Thailand. They assert that in such EFL contexts, although plenty of time and effort are spent on the improvement of EFL education standards, language learners cannot speak English fluently.

The EFL teaching programs in Turkey have been revised, and English classes are now compulsory starting from the second grade (Ministry of National Education, 2013). However, according to the comprehensive report of TEPAV and the British Council (2014), even though students have over 1000 hours of English classes by the end of their high school education, the vast majority of students in Turkey still have only rudimentary English. As the title of this paper suggests, the difficulty of speaking English is generally explained by EFL learners in Turkey with the statement 'I can understand English but I can't speak'. This statement is so commonly heard in society that it would be true to use the metaphor "syndrome" to describe this situation. A syndrome is defined as “a type of negative behavior or mental state that is typical of a person in a particular situation” (Cambridge Dictionaries Online).

In spite of the importance attached to improving speaking skills in teaching English as a foreign language (Egan, 1999), revising the methods of teaching speaking skills has not received the attention it deserves, and it has become an almost neglected skill (Scarcella & Oxford, 1992; Brown & Yule, 1983; Ur, 1996). Instead of speaking, the focus has generally been on grammatical accuracy (Blair, 1991; Richards & Rodgers, 1986). Furthermore, Wang (2006) claims that there are many problems in learning and teaching spoken English. Therefore, he suggests that studies dealing with English speaking skills have the potential to provide solutions to the problems encountered by the learners. Understanding the causes of problems in terms of speaking English is deemed essential to be able to organize more effective speaking lessons in such a way that deals with these problematic areas. Considering the importance of such studies, the current study investigates whether there is actually a 'I can understand English but I can't speak' syndrome among high school EFL students in Turkey. By collecting data from high school students who have been studying English for more than five years, the researcher has the objective to reveal whether students perceive themselves as successful or unsuccessful in speaking English. Additionally, the aim of the study is to explore the sources of motivation for learners who indicate that they can speak English and the causes of failure for learners who think that they cannot speak English. Finally, participants' suggestions about how they could improve their English speaking skills were focused.

In line with the aims of this study, the following research questions were formulated:

Speaking is generally described as “the verbal use of language to communicate with others” (Fulcher, 2003, p.23). It is also known as the primary motivational resource leading many people to learn a foreign language (Kaçar & Zengin, 2009). According to Nunan (1991), being able to speak the language is the most crucial aspect of the foreign language learning process, and knowing a language is often associated with the ability to have a conversation in the target language. In addition to its importance, speaking is also the most challenging skill among four basic language skills (Murphy, 1991; Mauranen, 2006), and thus it is generally mastered last by foreign language learners(Bailey & Savage, 1994; Richards & Renandya, 2002).

Both local studies in Turkey as well as international studies have been carried out to reveal the causes of the challenges of speaking English. For instance, the most frequently cited cause in Turkey is the old-fashioned teacher-centered EFL teaching approach (Gençoğlu, 2011; Güney, 2010; Özsevik, 2010). More specifically, Dinçer and Yeşilyurt (2013) conclude that the factors negatively influencing the speaking proficiency of EFL learners in Turkey are grammar-based teaching pedagogy, the fear of speaking English, lack of motivation to speak English, feeling inferior when speaking English in the classroom, and the lack of exposure outside the classroom. Similarly, Özsevik (2010) claims that although the current English teaching syllabus is based on the principles of the communicative approach, traditional methods (e.g., grammar-translation method) are still dominant in Turkey. Likewise, Karaata (1999) argues that many English teachers in the country think that teaching grammar constitutes the main component of language instruction.

Moreover, drawing attention to course books, Saraç (2007) states that the speaking skills might be neglected in the EFL course books in Turkey. On the other hand, researchers, such as Dil (2009) and Demir (2015) found that speaking anxiety and unwillingness to speak English are the main obstacles hindering the improvement of learners' English speaking skills in the country. On the other hand, as sources of English speaking anxiety for Turkish students, Öztürk and Gürbüz (2014) list the following factors: pronunciation, the fear of making mistakes and being evaluated negatively.

In another study, Gençoğlu (2011) revealed that being successful in speaking English depends on students' motivation, opportunities to practice the language, the atmosphere of the classroom, and the methods used in the classroom. Likewise, Toköz-Göktepe (2014) claims that misdirected methods, inadequate language knowledge, and lack of exposure to English outside the classroom are some of the sources of the English speaking failure in Turkey. In a similar vein, focusing on the causes of Turkish EFL learners' reluctance to speak English, Savaşçı (2014) came to the conclusion that the anxiety, fear of being criticized, and cultural differences are among the various reasons.

In addition to the above mentioned studies dealing with the causes of failure to speak English in Turkey, there have been other studies and arguments that have emerged in different parts of the world. These studies generally conclude that the source of difficulty in speaking English arises from the use of L1 in the classroom, focus on grammatical forms, cultural and phonological differences between L1 and L2, anxiety and limited exposure to English outside the classroom.

Pertaining to the use of L1, as argued byUr (1996) and Harmer (1991), learners often think that speaking the mother tongue is more natural and convenient in the classroom. Similar to students, many teachers also hold to the belief that use of L1 is more favorable to explain word meanings, give instructions, teach complex grammatical structures (Tang, 2002), and for classroom management (Littlewood, 1981). On the contrary, Awang and Begawan (2007) argue that students cannot speak English properly because of the use of L1 in the classroom. From Matsuya's (2003) perspective, the lack of communication skills and the focus on traditional grammar knowledge in English teaching programs are other possible reasons for the failure in terms of speaking English.

Another important cause of difficulty in speaking English is unfamiliarity with English culture (Shumin, 1997). In addition to cultural differences, the phonological differences between the first and the target language might also lead to some linguistic problems for students (Avery & Ehrlich, 1992), which makes it harder to speak English.

In addition, it is stated that the anxiety students feel when speaking the target language is another reason why speaking English is difficult (Liu & Jackson, 2008) . Focusing on the causes of anxiety, some other researchers revealed the following reasons: the lack of self-confidence (Shumin, 1997), shyness, fear of being humiliated, and lack of vocabulary (Urrutia & Vega, 2010).

Finally, limited exposure to English outside the classroom setting is a serious problem pertaining to speaking English (Lightbown & Spada, 2006). This is especially evident in EFL contexts where students share a common first language but have limited exposure to the target language outside the classroom environment (Bresnihan & Stoops, 1996) ; therefore, the lack of speaking practice opportunities can be regarded as a cause of English speaking failure.

Participants in this study are 293 high school students in two state Anatolian high schools in Bolu, a small city in the Black Sea Region of Turkey. The high schools were selected on the basis of convenience sampling in that the schools were in the city center, and thus easy to reach. Only the students who were available on the day of data collection took part in the study. The researcher confirmed with the school administration regarding the availability of the students. Students studying in the science lab or training in the gym were excluded from the study. Moreover, students who had exams or tight schedules were not recipients of the questionnaire.

All of the participating high school students have been studying English for more than five years starting from the fourth grade in primary school. Their age range was between 14 and 19. While only 10 of the students graduated from private elementary schools, the remaining 283 students were graduates of state elementary schools.

The scale used in this study was developed in Turkish by Hocaoğlu (2015) for university EFL students in Turkey. Based on a comprehensive literature review, Hocaoğlu designed her five-point (i.e., strongly agree, agree, partly agree, disagree, strongly disagree) Likert-type items dealing with the reasons behind the English speaking difficulties of English learners in Turkey. Having maintained the content and construct validity and reliability of the scale, she finalized the scale including 18 items in two sections.

The first section of the scale contains 15 items dealing with the reasons for not being able to speak English. This part has three sub-dimensions as reasons arising from theoretical knowledge and personal issues (e.g., 'I do not have an opportunity to practice my English'), English education (e.g., 'Our English teachers spoke Turkish in the lesson') and culture (e.g., 'I do not know much about English culture'). On the other hand, the second section of the scale described by Hocaoğlu (2015) as the motivation sub-dimension includes three items indicating the motivational factors enabling the participants to speak English (e.g., 'I feel confident while speaking English').

In this study, participants first marked whether they believe that they can or cannot speak English. Those who indicated that they cannot speak English filled out the first section of the scale while students who believed that they can speak English only expressed their opinions about the items in the second section. Only one item aiming to reveal whether university English course books include colloquial language was excluded from Hocaoğlu's (2015) scale as the participants in this study are high school students. Therefore, the scale used in this study has 17 items. Moreover, an open-ended question which sought to reveal participants' suggestions about ways of improving their speaking skills was included at the end of the scale.

The data collected by the Likert-type items were analyzed using SPSS 23 while the data collected via the open-ended question at the end of the scale was subjected to content analysis. The scale was found by Hocaoğlu (2015) to have a Cronbach's alpha coefficient value of .837, which proves that the scale is reliable (Büyüköztürk, 2012). The value was found to be .823 in the present research context.

While analyzing the quantitative data, frequency and percentage calculations were used. In the process of analyzing the qualitative data, the common themes in the participants' suggestions were revealed. All of their suggestions were analyzed, and similar suggestions were grouped according to common themes (Patton, 2002) .

The findings related to each research question (RQ) are presented below in frequencies (f) and percentages (%).

To find an answer to this research question, the frequency and percentage of students' choices of either of the two statements (i.e., 'I can speak English' and 'I cannot speak English') were calculated. The analysis of their responses led to the following bar chart (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Students' Beliefs About Whether they can or cannot Speak English

Looking at the bar chart, it is realized that out of 293 high school students in two high schools, while 209 (71.4%) participants believe that they cannot speak English, only 84 (28.6%) hold the idea that they can speak English.

Tables 1, 2, and 3 illustrate the findings related to the reasons perceived by the participants who marked 'I cannot speak English' (71.4%). On the other hand, Table 4 summarizes the motivational factors perceived by students who indicated 'I can speak English' (28.6%).

Table 1 presents findings related to the causes arising from theoretical knowledge/personal reasons. The item stating that 'The English education in Turkey mostly depends on grammar rules' was agreed upon (’agree’ and ‘strongly agree’) by the vast majority of participants (86.6%). The second most commonly agreed upon (85.6%) item is 'I have not been to an English speaking country for at least a year'. The third most frequently agreed upon item is 'The word order in English is different from the word order in Turkish' (77%). On the other hand, the fourth most widely agreed upon item is the lack of speaking practice opportunities (72.3%). Also, the item 'I feel anxious while speaking English' was agreed upon by more than half of the participants (64.6%).

As demonstrated in Table 2, as for the reasons related to English education in Turkey, more than half of the participants associated their lack of speaking skills with learning English via Turkish (57.4%) and with the high school English course books which do not include colloquial English (57%). It is also noteworthy that nearly half of the participants (46.4%) agreed that they fail to speak English because their English teachers speak Turkish rather than English in the lesson.

Table 3 illustrates participants' perspectives about the role of culture in their failure to speak English. According to the majority of participants (66.1%), their lack of knowledge about English culture hinders them from speaking English. Moreover, the item 'I do not sufficiently listen to English (songs, radio, films)' was agreed upon by 40.7% of the participants while it was disagreed by more participants (43%).

Table 4 illustrates the reasons indicated by the participants who hold to the belief that they can speak English (28.6%). This part of the scale constitutes the motivation subdimension.

As can be realized from Table 4, out of 84 students who believed that they can speak English, the vast majority of the participants (89.3%) indicated that they are eager to speak English. Also, many students (85.7%) stated that they know a sufficient number of words to express themselves in English.

At the end of the scale, participants were asked to list what should be done to improve their speaking skills. Their responses were subjected to content analysis which led to two themes as suggestions for school and suggestions for outside the school.

The frequencies (N) of these responses under each theme are given in Table 5 as indirect statements. Only the responses given commonly by at least two participants were included on the table.

The analysis of the qualitative data presented in Table 5 revealed that students think that there are certain issues to be considered both by their schools and by themselves. On one hand, for instance, it was recommended by the participants that schools should replace the grammar-based lessons with conversation-based lessons (N:8), and the lessons should be designed in a more enjoyable manner (N:6).

It was also suggested that native English speakers should teach conversation lessons at school (N:5), and more emphasis should be placed on vocabulary teaching (N:3) as well as on daily English speaking (N:2). Moreover, it was suggested that there is a need for greater focus on the importance of speaking English at school (N:2). In addition, bringing back the preparatory English programs to high schools was considered advisable by a few students (N:2) (i.e., There used to be an initial one-year intensive English preparatory program at high schools in Turkey before the 2005-2006 academic year).

On the other hand, as for out-of-class learning as a means of improving their speaking skills themselves, students suggested that the following activities should be carried out: playing computer games (N:11) (e.g., CS:GO, GTA 5), watching English films or videos (N:7), going abroad/attending students exchange programs (N:6), attending a private course (N:5) and chatting with friends (N:3).

The aim of this study was to find out whether high school students believe that they can or cannot speak English. Also, the reasons for their failure or success in speaking English and their suggestions to improve their English speaking skills were investigated. This study set out to help accumulate the body of knowledge about the causes of English speaking failure in Turkey and to enable teachers, course book writers and authorities to take necessary actions to deal with this failure.

Out of 293 high school students enrolled in two state Anatolian high schools, while only 84 hold the idea that they can speak English, 209 participants believe that they cannot speak English. This finding concurs with the metaphor used in the title of the present paper (i.e., 'I can understand English but I can't speak Syndrome'). It would be fair to claim that the inability or the difficulty of speaking English in Turkey has almost become a syndrome requiring treatment. This study showed that despite 1000+ hours of English classes until the end of 12th Grade (TEPAV & British Council, 2014), this syndrome is still common among high school EFL learners in the context of the study. Moreover, being able to understand English without being able to speak is a problem not only in Turkey (Koşar & Bedir, 2014; Dinçer & Yeşilyurt, 2013) but also in other countries(Tatham & Morton, 2006).

Many empirical studies have focused on the causes why EFL learners in Turkey are not very successful in speaking English (Dinçer & Yeşilyurt, 2013; Tercanlıoğlu, 2004; Özsevik, 2010; Karaata, 1999; Saraç, 2007; Gençoğlu, 2011;Toköz-Göktepe, 2014; Savaşçı, 2014; Dil, 2009; Demir, 2015; Öztürk & Gürbüz, 2014). In addition to these empirical studies, the problem of English speaking among Turkish students has always been at the forefront in Turkish press (British Council, 2015-2016). This has been exemplified in some newspaper columns with titles such as 'Why can't Turks speak English yet?' which were purposefully written to attract attention to the problem of speaking English in the country (Sak, 2012).

As for the reasons for failure in speaking English, the most commonly indicated causes in this study are as follows: grammar rules dominating the EFL education in Turkey, not being able to go to an English speaking country, feeling anxious while speaking English, lack of speaking practice opportunities, lack of knowledge about English culture, learning English via Turkish and the course books which do not include colloquial English.

As far as the focus on grammar is concerned, many students stated that the grammar-driven English education in Turkey prevents them from speaking English. Some students even suggested replacing grammar-based lessons with conversation-based lessons, and having conversation classes with native English speakers. As many researchers also claim, despite the government-initiated meaning-oriented reform movements, English teachers in Turkey are not very familiar with CLT and follow a teachercentered traditional grammar teaching method (Uysal & Bardakçı, 2014; Özsevik, 2010; Kırkgöz, 2007; Gençoğlu, 2011; Güney, 2010; Tercanlıoğlu, 2004). Similarly, Dinçer and Yeşilyurt (2013) argue that grammar-based classroom practice is one of the causes hindering English speaking proficiency in Turkey. Furthermore, this problem is not only limited to the Turkish EFL context. For example, Matsuya (2003) observed that the main cause of the poor speaking skills of Japanese students is the traditional emphasis on grammar and the lack of focus on communication.

Also, it was indicated by some participants in this study that the high school English course books do not include colloquial English. Saraç (2007) regards the course books as the cause of English speaking failure by stating that speaking activities and practices are not given enough attention in the English course books in Turkey. Similarly, Toköz-Göktepe (2014) maintains that the materials used in the classroom are other sources of the problem.

Other commonly marked reasons for the problem are the lack of travel opportunities to countries where students can practice their English and the lack of speaking practice chances outside the classroom. This finding also echoes the results of the previous studies revealing the lack of outof- class speaking opportunities (Toköz-Göktepe, 2014; Gençoğlu, 2011). In countries such as Turkey, where English is spoken as a foreign language, the classroom is the only place in which learners can get exposure to the language. As students only rely on classroom instruction in EFL contexts, lack of exposure to English outside is a serious issue in the development of their communication skills (Xiao & Luo, 2009).

The relevant literature also provides supportive evidence for the importance of out-of-class foreign language learning for the development of foreign language skills (Hyland, 2004; Sundqvist, 2009; Richards, 2015). The analysis of thequalitative data in this study also revealed some suggestions in line with the importance of out-of-class English speaking opportunities. For instance, some students recommended that the following activities can be carried out to continue their English learning process out of the classroom walls to improve their speaking skills: playing computer games, watching English films or videos, going abroad, attending student exchange programs, attending a language course and chatting with foreign friends.

From the participants' perspective, another important source of the failure to speak English is anxiety. This finding corroborates the results of studies carried out both in Turkey (Dil, 2009; Demir, 2015; Öztürk & Gürbüz, 2014; Savaşçı, 2014) and in other contexts (Liu & Jackson, 2008). Moreover, this study revealed that the lack of knowledge about English culture and pronunciation are other sources of the problem. Cultural unfamiliarity was also mentioned as a source of linguistic problems in the relevant literature (Shumin, 1997). Not only cultural differences but also phonological differences negatively influence the English speaking progress of the learners. The fact that phonological differences between the two languages might cause deficits in terms of speaking English was also underlined in the literature (Avery & Ehrlich, 1992).

Finally, other issues indicated by the majority of participants as sources of the inability to speak English are learning English via Turkish and teachers' speaking the mother tongue in the lesson rather than the target language. Related to the use of L1, it is asserted that both learners and teachers have the tendency to use L1 in the classroom (Ur, 1996; Harmer, 1991; Littlewood, 1981), and the use of L1 in the classroom are likely to negatively affect learners' English speaking progress (Awang & Begawan, 2007).

The reasons discussed above as well as the supporting literature led to the following implications for the context of the study:

In conclusion, the problem as far as speaking English is concerned in Turkey is described in this paper by using the metaphor 'I can understand English but I can't speak' syndrome. It is believed that understanding the causes of this syndrome can help prevent its occurrence by organizing our classes in such a way to cope with the problematic areas as perceived by students in such studies. Therefore, further research studies involving more participants at different education levels in Turkey should be carried out. Considering that the problem with speaking skills is also valid for other EFL contexts such as China, Thailand and Japan (Dinçer & Yeşilyurt, 2013), similar studies exploring the reasons for English speaking failure should be conducted in these countries. Also, as the data was collected only via a Likert-type scale in this study, future researchers can carry out longitudinal studies in which both qualitative and quantitative data collection instruments are used.