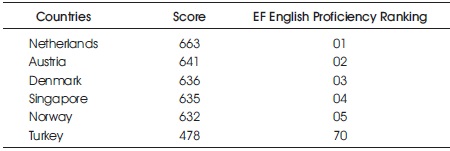

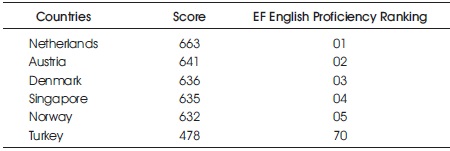

Table 1. Countries in Top 5 and Turkey for EFEP Rankings

As English is widely accepted as a lingua franca in today's world, the importance of the language has been acknowledged globally in the present case. To rank the countries in terms of their English language proficiency, the EF Proficiency Index is prepared each year. In this study, five countries having the highest scores according to the Index (2021) were taken into account together with the English language curricula of the top five ranking EFL countries (Netherlands, Austria, Denmark, Singapore, and Norway). The English language teaching programs of these countries were analysed and compared in terms of the starting age, language assessment, and course content, adding to the comparison list a low-ranking country, Turkey. The data elicited through document analysis propounded the idea that overall, the objectives of English language curricula in these five countries have many common features and similarities. On the other hand, developing positive attitudes towards learning English is emphasised in the Turkish EFL context, and four basic language skills are treated separately in different grades. While other countries give prominence to communicative competence and communication skills together with the cognitive side of the language learning process, the affective components of the language learning process are emphasised in Turkey. Contemporary formative assessment techniques are also recommended in this continuum.

As a well-known fact, English language is accepted as a lingua franca and is commonly employed in science, technology, and business relations on a global scale. The need to incorporate the teaching of English into educational programs has been acknowledged by governments and educational institutes in the last decades and language teaching policies are specified accordingly. The English language, with its position as the international language of trade and media, and ELT are viewed as the cornerstones of the Council of Europe language education policy (Council of Europe, 2001a). In a similar vein, the promotion of the English language in primary and secondary schools is a matter of concern to many European countries. A great number of countries are attentive to the quality of their English language teaching programs and are in favour of orienting their country towards many educational reforms, structural adjustments and alterations in English language teaching and learning programs.

This study analyses the English language teaching policy and practices of five countries ranking very high proficiency in the EF Proficiency Index 2021. EF English Proficiency Index is a ranking of 112 countries and regions by English skills and investigates the places where English proficiency is higher than the rest of the world. According to the EF Proficiency Index edition of 2021, the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark, Singapore, and Norway are the countries that are ranking very highly in proficiency, respectively. In addition to these top five countries, a low-ranking country was added to this comparison and English language education practices in Turkey are also examined in this study. Teaching methodology and materials, the starting age for learning English, the assessment of English education, and number of class hours are analysed within the specific educational contexts of these countries. Table 1 shows the countries in top 5 and turkey for EFEP rankings.

Table 1. Countries in Top 5 and Turkey for EFEP Rankings

The document analysis provided the data for the English teaching programs of these countries and revealed the fact that there are striking similarities in the English language teaching objectives of these five countries.

Together with these similarities, differing practices and the most salient aspects of English language education in these countries with regards to the content, teaching or learning process and assessment were also identified in the study. In a general sense, an interactive heuristic and hands-on approach to language learning was adopted in these countries to exhort students to adopt the idea that English is not a subject to be taught. The effort to meet and specify the evolving educational reforms and st requirements of the 21 century results in higher quality language education and increases the satisfaction gained from current teaching procedures and practices. These programs are responsive to existing contextual variables and constraints and are in alignment with the social, economic, and educational requirements of a given nation (Enever, 2011). On the other hand, current practices generally focus on structural and lexical units of English in the Turkish EFL context. Overloaded syllabuses and the disconnection between beliefs and practices are important factors hindering the success of ELT programs in Turkey.

Additionally, there are some other components affecting the English proficiency level of people in these five countries. Onset age, teaching priorities, and methodology have a great influence on the success of English teaching programs. English has a high status in educational institutions and in society by the same token. Notwithstanding that there is a degree of uncertainty about the optimal starting age for learning English, these countries have a plethora of opportunities outside the classroom setting in order for students to be exposed to authentic language materials, and this milieu compensates for possible deficiencies and hindering factors in the education systems.

Grounding itself in the results of the EF Proficiency Index, this study sets out to analyse the similarities and differences in the English language education systems and contexts of five countries, together with Turkey, and particularly focuses on the onset age, assessment, and teaching methodology in these countries.

Document analysis was carried out for this study after learning the related literature. The trust worthiness and availability of the source are the two basic criteria in the data collection process. Accordingly, data regarding the English language policy of target countries were collected from scholarly studies, Eurydice, OECD resources and the websites of the studied countries' ministries of education in this qualitative study (Alsagoff, L. 2012). As for the selection of countries for the study, the criterion was the Education First Proficiency Index scores of these countries in 2021. Education First English Proficiency is an initiative aiming to rank countries according to adults' proficiency levels of English in many countries through out the world.

The research questions leading to this study are given as follows.

The documents were analysed in accordance with the research questions of the study. Additionally, data analysis was conducted in the domains of starting level of English lessons, language teaching objectives, approaches, and methods in the learning-teaching process, assessment, and evaluation of course content in public schools.

As a country geographically surrounded by larger European countries, the Netherlands is a small country (17 million people) with significant international orientations (Michel et al., 2021). Dutch and Frisian are their national languages. However, Frisian is spoken by a smaller portion of its inhabitants who are living in the Northern Province of Friesland (approximately 400,000 people). As stated in the European Commission report, 90% of the Dutch are proficient enough to have a conversation in English. The English language and its influence are so ubiquitous that it is no longer regarded as a foreign language by a group of people in the society (Edwards, 2016). Inline with this fact, English spoken films and TV programmes are not dubbed in a general sense.

As for the Dutch educational system, most children start school at the age of four (compulsory from age five), and primary education consists of eight consecutive years. English at primary schools was made compulsory in 1986, and as of this date, English lessons have been offered in the last two years of primary school (students aged between 10 and 12). Despite a lack of guidance regarding the implementation process, tests, or course books, the Dutch system promises to provide 80 hours of early English in the last two years of primary education. The most striking general feature to be found is a focus on oral interaction with other speakers of English and understanding simple written information (Fasoglio et al., 2015). On the other hand, some schools (1000 out of 7000 schools) chose to adopt an earlier start in English language education for children aged 6-10. 16% of the primary schools in the Netherlands are offering early English as a Foreign Language learning program at the present situation.

As of 2016, the government permitted a maximum of 15% English in primary schools, either for English lessons or other subjects taught in English. The Dutch education system offers drip-feed English practice in primary schools, generally one 45-minute lesson per week. This situation results in limited exposure to English with this small amount of classroom time. However, out-of-class exposure and out-of-class English media consumption play a significant role in students' English language learning process. In addition to all these factors, the socioeconomic status of students plays a key role in English learning at primary schools. Accordingly, children from more affluent house holds possibly attend bilingual schools in primary education.

As of 2014, EFL has become compulsory for all secondary school students (vocational, general, and pre-university level) in the Netherlands. When the children reach the age of 11 or 12 and graduate from primary school, they attend one of three types of secondary schools depending on their school grades, national examination results, and scholastic aptitudes, pre-vocational, pre - professional and pre-academic. Additionally, there are more than 130 schools providing bilingual secondary education in these three scholastic tracks (Nuffic, 2019). In this process, teachers undergo training in the Content and Language Integrated Learning Approach (CLIL) together with bilingual pedagogy (Coyle, Hood, & Marsh 2010). However, the negative wash back effect of national central exams (determining 50 % of the final grade) is another crucial issue in as much as these exams focus on reading comprehension with a multiple-choice format rather than target language society, culture, literature, and related oral skills in the target language (van Dée et al., 2017).

Additionally, language teachers generally employ target language for social talk while other instructions are provided in Dutch ( Haijma, 2013).The current curriculum reform adopts a bottom-up approach and includes a wide range of stakeholders from the field.

Accordingly, core objectives and attainment levels of students will be reformulated.

In 1993, the Dutch government executed a plan to revise junior secondary education, which is for children aged 12 to 15. These reforms paved the way for a diversity of languages on offer, and the focus was on a communicative approach. With this reform, English was also accepted as a core subject in addition to Dutch and Mathematics ( Fasoglio et al., 2015). With the establishment of the CEFR ( Common European Framework, 2001), necessary regulations were decided in pursuit of the integration of CEFR attainment levels into the Dutch education system and exam syllabus from 2009 to 2011. In general, higher levels of proficiency are expected for receptive skills. For instance, the proficiency levels of students in English reading and listening need to be at B1, while they are only at A2 for speaking and writing. Interestingly, students do not reach target attainment levels in writing while they reach or exceed these levels in speaking skills ( Fasoglio & Tuin, 2018).

Austria is known for its shorter span of comprehensive schooling among European countries, and after Grade 4 in primary school, students attend either general academic secondary schools or middle schools that equip them with the necessary knowledge regarding professional life ( BMBWF, n.d.). They can also move on to upper secondary levels of education after middle schools. However, some disadvantages accompany this dual-track education system. Middle schools generally accept students whose families are from a lower socioeconomic background or a migration background and who speak languages other than German at home ( Statistik Austria, 2021).

As reflected in the Austrian Constitution (Art 8, Section I), German is accepted as Staatssprache der Republik (state language of the republic), however English is the most widely learnt foreign language in the country given its unique status as main global and European lingua franca. The language policy in Austria can be viewed as globalized bilingualism ( Smit, 2004, p.82) in which German is the default language of schooling while English is the sole additional language that all the Austrian students have to learn in their formal training process. According to the results of the Euro barometer survey conducted in 2012, 73 percent of all Austrians claim that they regard themselves proficient enough to strike up a conversation in English ( European Commission 2012, 21). A key indicator of the role of English in Austria is the linguistic landscape, referring to "the language of public road signs, advertising billboards, street names, place names, commercial shop signs, and public signs on government buildings' ( Landry & Bourhis, 1997, p. 25). As Spolsky (2004) indicated, all these components are the hallmarks of language policy in a country, especially topdown language policy decisions rather than de jure policy action. Schlick's Studies (2002, 2003) indicated the relatively strong presence of English in Austria's linguistic landscape. Apart from this usage, English is partially positioned as an element of Austrian public life through theatre productions, newspaper articles, exhibitions, and online services. Given that the growing internalization has had a great impact on the country, English has a semiofficial role in some contexts in Austria. Additionally, Schwartz's study (2016) focused on the close connection between exposure to extramural English and language gains in an Austrian context. All in all, English is the most prominent language on display after German and the most frequently used additional language in the public sphere in Austria ( Hickey, 2019).

English is the first foreign language for almost 99 percent of learners ( Nagel et al., 2012, p. 86), while it is also highly visible as the medium of instruction in the form of CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning), especially at a specific type of upper-secondary technical college called "Hohe Technische Lehranstalten" (HTL). English was made mandatory for grades 3 and 4 at the primary level in 1975, and then the duration was then prolonged for four years in 2002.

However, the success of English education at the primary level is evaluated as disappointing because of "overambitious policy making together with unrealistic educational planning" ( Dalton-Puffer et al., 2011, p. 193). Although language policies have been recently amended to serve the purpose of "globalized bilingualism," some important problems and weaknesses are neglected in this process.

Between 2006 and 2008, the Language Education Policy Profile procedure was established after the visit of experts from the Council of Europe ( Extra, G., & Yagmur, K. 2012). It is regarded as a self-evaluation report of a country's language education policy and precautionary measures are taken after the end of the process is reported by extern experts appointed by the Council of Europe. The report also addresses the role of bilingual schools for autochthonous minorities. The Council of Europe promoted some significant aspects in language teaching and the most outstanding ones are notional functional language teaching, threshold levels of the CEFR, the European Language Portfolio(ELP), and the establishment of the European Centre for Modern Languages in Graz in 1995.

Denmark has been a member of European Union since 1973 as a Northern Europe country (EU, 2016). Lifelong learning, education for all, self-governance, and projects are among the specific and most salient features of Danish education system ( Eurydice, n.d.). The Danish linguist Paul Christophersen's article delineates the 'special' position of English in Denmark referring to a guide for Danish teachers dated 1976. The aim mentioned in this guide is to form a bilingual society with English as the second most significant language having a weighty influence in many fields of the society. The same author also claimed that “Indue course, no doubt, Denmark will become a fertile field for the study of the characteristics of a bilingual society. Everybody will know some English, but there will be differences in competence and preference” (Christophersen, 1991, p.9). In line with this strategy, English, as the language of international research, is the dominant language in popular entertainment, higher education, and business world in Denmark.

However, in the last two decades there are some strategies and studies aiming to preserve the domains (school, higher education, and research) that Danish is losing while trying to keep the development of English at a steady pace ( Dansk Sprognævn, 2012). In other words, this strategy aims to reach “balanced domain-specific bilingualism ( Harder, 2008).

As for the place of English in Danish education system, English language teaching starts at first grade and th students attend these courses until the end of 12 grade level.

Rather than centrally developed curricula, schools implement their own ELT programs with in a general framework. Four language skills are not treated separately in the Danish education system, especially written and oral communication skills are accentuated in the whole process of English language education ( SIL, 2016b). The topics of the lessons are not determined before hand, and they are chosen by language teachers based on their own teaching experience provided that the topics serve for the development for a land written communication skills in English. In general, studentcentred activities, drama, role-plays, and the use of the target language for communicative purposes are emphasized in governmental documents. As for the evaluation in teaching English in Denmark, teacher analyses, interviews, and observations in specific reference to learning goals are main techniques which are employed in this process (SIL, 2016).

The duration of primary school is 6years in Denmark. The educational structure in Denmark is organized as 6+3+3, and the compulsory education lasts for 10 years ( Danish Ministry for Children, Education and Gender [DMCEG], 2016). After the introduction of the 1994 folkeskolere form, English became compulsory in Grade 4. However, as of 2018, English instruction starts in Grade 1 and many students continue until the end of post secondary studies. By the end of upper secondary schooling (gymnasium), most students graduate with B2 competences in English (CEFR, 2001; European Commission, 2017). Students attend different type of gymnasiums, and the focus varies accordingly. While STX is more traditional, HTX has a technical orientation. EUX is vocational and HHX is business oriented, but English is compulsory in all these different types of gymnasiums. On the other hand, the clusters of courses together with class time requirements change depending on the upper secondary schools they enrol in.

This learning milieu fosters students' broad exposure to English out side the school and additionally English language is generally regarded as a second language rather than a foreign language by most prominent scholars (Færch et al., 1984).

Cartoons, news, and movies are also shown in their original form, in other form without being dubbed. Accordingly, children are exposed to oral English from an early age. This situation is defined by the term extramural English coined by Sundqvist (2009, p. 1) in order to refer to English language input that students are exposed to outside the classroom. It is also directly related with the notion of incidental learning defined by Laufer and Hulstijn (2001, p. 66) as “learning without an intent to learn, or as the learning of one thing, e.g., vocabulary, when the learner's primary objective is to communicate.” All these factors motivate students to under stand the language input provided by outer sources and provide opportunities for students to engage in heuristic learning activities.

As Singapore became a British colony in 1819, English had a dominant position in the political administrative system (Dixon, L. Q. 2005). Since the independence from Malaysia in 1965, English has been accepted as a resource to contribute the country's economic and social development (Lim, 2004) and the country is one of the leading financial centres in the world together with London, New York, and Hong Kong. When the role of English in the interaction between internationalization and globalization is considered, English is regarded and functions as a global language (Crystal,2003). Moreover, English, as a neutral linguafranca, functioned as a cultural unifier for inter-ethnic communication (Bokhorst-Heng 1998, cited in Deterding 2007: 86). In a similar vein, English language functions as a tool facilitating the state's strategic cosmo polit an ambitions.

English language education is accepted as a major conduit between the local people and the globalized world while serving for capital needs of the country at the global market place (Silver, 2005).

However, there is a distinction between Singapore Standard English (SSE)and Singapore Colloquial English (SCE) or Singlish in scholarly studies. Although Singlish causes tension with official language policy on Standard Singapore English, it is accepted as a badge of identity (Stroud & Wee, 2007) since most of Singaporeans shift easily between Singlish and Standard English. The English Program in the country aims to prepare students to become internationally intelligible and to have functional clarity in international encounters.

English, Chinese, Malay and Tamil are four official languages in the country. English is taught as the first language in schools and accepted as the main medium of instruction in national education. The other three languages are the mother tongue languages of major ethnic groups in the country. The Ministry of Education Singapore (n.d) states that “pre-school children will learn in two languages: English as the first language and Chinese, Malayor Tamil as a mother language”.

Bilingual English language teaching policy in Singapore, adopted since 1966, enables the students to nurture their English and mother tongue language skills synchronously. In the1980s, the country adopted a Communicative Language Teaching Approach (CLT) and provided opportunities for students to practice using English with the help of authentic language materials rather than just focusing on rote vocabulary exercises and abstract grammar rules. In addition to these developments, English language, with its long history of institutionalized functions in the state, has been the primary medium of instruction at all levels since1987.

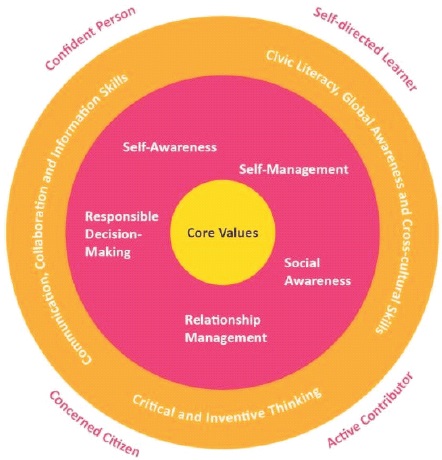

The Ministry of Education of Singapore has adapted its language education programs to ensure that they are responsive to the changing needs of the time. After the review of the English language teaching program in 2006, the latest reform of the English language syllabus was completed in 2010. The most important feature of this latest reform is the adoption of a systematic approach to teach language skills with authentic and meaningful language resources. English language education starts early, and kindergarten and child care centres offer a three- year education for children between 3 to 6 years of age. The English Language Institute of Singapore, proving instrumental in providing a centre of academic excellence in English language teaching, was also founded by Prime Minister Lee and Chuain 2012. The Whole School Approach to effective communication has been espoused with the contributions of the English Language Institute. Figure 1 shows the framework for 21st century competencies and student outcomes.

Figure 1. Framework for 21st Century Competencies and Student Outcomes © Ministry of Education, 2014

The Strategies for English Language Learning and Reading ("STELLAR") programme is also employed at the primary level and English is delivered with the help of short stories and texts together with explicit grammar instruction. Apart from STELLAR Programme, the Learning Support Programme ("LSP") has been conducted in all primary schools since 1998 and aims to provide support for students having weak English language literacy skills.

In addition to all these developments, the language environment in Singapore is conducive to nurturing students' English language literacy at all levels. A growing population of students has the opportunity to speak English at home (32 % in 2010). It rose to 48,3 % in 2020 (Singapore Department of Statistics, p. 23). In a similar vein, a range of English media outside school and English medium instruction help them to practice and use English in different milieu and occasions. Apart from all these factors, mutually reinforcing relationship between globalization and English language paved the way for the role of English in Singapore. All in all, the studies coalesce into three main overlapping themes in this context and these are the linguistic ecology of Singapore, the status and use of English in this multilingual society, and lastly the effect of globalization on educational practice and school contexts ( Lo Bianco et al., 2021).

With the role of English as a linguafranca in global arena, English language education gained great prominence in the last two decades. In a similar vein, a certain level of English language proficiency is a prerequisite necessary to engage in active participation in different realms of society. The present national conjuncture is also the same in Norway in terms of the effects of English language on public domains and digital arena and English has a high status in the country (Vattøy, 2017). Although English does not have an official status in Norway, a great number of Norwegian students learn and acquire English as a second language rather than a foreign language. In a similar vein, Rindal (2014) acknowledges the status of English in Norway as close to that of an official second language, mirroring the situation in Sweden (Bardel et al., 2019) and Denmark (Fernández & Andersen,2019).

Norwegian students have a higher level of English proficiency compared with other students in other countries (Bonnet,2004; Education First, n.d.). On the other hand, Hellekjær (2010) drew attention to the fact that Norwegian students are better at Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills (BICS) in English rather than academic English and they have limited Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) in English (Cummins, 1984). The overarching approach to English language education is communicative in national policy documents.

The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe, 2001) embodies the English Language teaching program in the country and the positive effects of practical language use and communicative competence are accentuated in related documents (Ministry of Education and Research, 2004; Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2020).

As for the use of target language in EFL classes, there is not a direct statement in the Norwegian curriculum for the subject of English referring to it as the sole medium of instruction in educational institutes in spite of scholar's recommendations regarding the maximal use of target language in these classes (Krulatz et al., 2016). These scholarly works from Norway also indicated that TL is used more extensively in secondary school L2 English classrooms (Brevik & Rindal, 2020) when compared with the use of English in primary schools (Krulatz et al., 2016).

The Common European Framework of References for Languages (CEFR) plays a decisive role in determining the Norwegian national English language curriculum, especially with its can-do statements. Children start primary school at the age of six in Norway and they have access to instruction in English beginning from the first year of primary school. Compulsory education lasts for 10 years, and it consists of two stages, the first of which is primary school (1-7) to be succeeded by lower secondary school (8-10). They have 588 hours of English language training throughout the primary school and teaching hour duration is 60 minutes in the education system.

Additionally, teachers have a heuristic 'hands-on' or interactive heuristic approach to learning, albeit students' higher degrees of receptive skills than productive skills. Some important national initiatives, e.g., Assessment For Learning (AFL) and Classroom Interaction for Enhanced Student Learning (CIESL) (Both funded by the Norwegian Research Council), were purposed to improve the quality of English language teaching in the country.

As for exposure to English in undertaking leisure activities, any of the English media is not dubbed in the country and Norwegian students handily make access to English media with the help of latest advances in technology. All these foster broad exposure to English language. British English is generally accepted more prestigious and is favoured by community with reference to the norms in English pronunciation (Rindal, 2010). Not withstanding, Norwegian learners are better at American pronunciation.

Learning a language is valued by Turkish people since the time of the Ottoman Empire and especially foundation of the Turkish Republic by Gazi Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1923. As a matter of fact, different foreign languages were popular in different stages of history. The Turkish proverb which says 'One who speaks one language is one person, but one who speaks two languages is two people' underlines the value and importance placed on foreign languages by Turkish people. Accordingly, English language instruction is included in all stages of Turkish education system.

In his book titled 50 Soruda Dil Öğrenme (Language Learning in 50 Questions), Balçıkanlı (2021) provides significant information regarding the historical development of foreign language education in Turkey. One of the most significant developments in the 21st century is the introduction of compulsory foreign language courses in 1924. Department of Foreign Languages of Gazi Institute of Education was also opened in 1933 after the establishment of the Turkish Republic. Georgetown Project is another important development in the Turkish EFL context, and it was conducted between 1953-1965. Maarif Colleges, the first of which opened in 1955, set a very successful example in foreign language education and teachers and students were selected by exams (Balçıkanlı, 2021). In 1975, Maarif Colleges were replaced by Anatolian high schools. When high school education was increased to 4 years in 2005, the preparatory class of many Anatolian high schools, which provided a successful teaching of English, was abolished. With the termination of effective practices in Anatolian high schools, the desired and expected success in foreign language education was not achieved in this period.

As a country neighbouring Europe, Turkey applied for the membership of European Union in 1987 and negotiations began in 2005. Accordingly, some educational reforms in language teaching were introduced in 2005 and 2013. A constructivist language teaching was adopted in these reforms. As for the most salient features of this teaching philosophy, constructivism is highly student-centred and it is a requirement for teachers to facilitate engagement, active learning, cooperation, and reflection in their classes (Pardamean & Susanto, 2012). The onset of English language teaching was lowered to 2nd grade from 4th grade in primary schools. The main aim in 2nd, 3rd and 4th grades is to help students develop positive attitudes towards learning English. In other words, the affective side of language learning process is emphasized in these programs. As for 5th, 6th, 7th, and 8th grades' ELT programs, the aim is to increase interests in learning a language and th th th using it in real life contexts (MONE, 2013). For 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th grades, students are to be provided with a motivating and entertaining learning environment so that they could speak English fluently, effectively, and accurately (MONE,2014). As for targeted skills in teaching English, listening, and speaking skills are the focus of the program for 2nd, 3th, and 4th grades and they have a limited level of reading and writing activities. However, the focus is on the integration of four skills in the 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th grades (MONE, 2014).

Compulsory education is twelve years and students start school at the age of five and a half. The English teaching program follows the principles and descriptors of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, Learning, Teaching and Assessment (CEFR). In the first stage of education system, namely 2nd, 3nd, and th 4th grades, English is taught for two hours a week while it is three hours a week for 5th and 6th graders. Between 7th grade and 12th grade, English is taught for four hours a week. In grades 2nd, 3rd, and 4th of primary school, there is a skills-based program focusing mainly on listening and speaking skills. The use of language in an authentic and communicative environment is stressed in the program by the Turkish Ministry of National Education (TMNE) and additionally the English language is evaluated a same communication rather than a subject to be taught (ELT Program of TMNE, 2017). However, the problems encountered in the application of the program hinder the students from reaching a certain level of English proficiency throughout the whole education life.

As of 2013, the students began learning English in the second grade in primary school. Before that time, primary school students started English at fourth grade (MONE, 2013). Speaking, writing, listening, and reading skills are addressed as separate entities in these programs and affective state of students and their positive attitude towards English learning process are regarded as superior to cognitive goals when compared with other European countries. Top five countries in EF Proficiency Index centre on communicative competence and communication skills of students rather than evaluating language as a mechanical tool.

Not withstanding that a communicative approach to English language teaching was introduced some years ago in Turkey, it has not taken root in all grades of school system or hasn't been pursued with conviction. The fundamental purpose for teaching English is to foster intercultural and global competency inorder to emulate the success of high proficiency countries in EF Proficiency Index.

As of 2014, the starting age for learning English matter was predetermined in Denmark and it was lowered from third to the first grade. As for the English language teaching program in Singapore, there is a definition of bilingualism peculiar to Singapore and is defined by the government as proficiency in English and one other official language and the policy is named as English knowing bilingualism (Pakir, 1994, p.159).

Accordingly, the influence of English-medium instruction is so ubiquitous in Singapore that students learn all the subjects in English when they start primary school except for the mother tongue subject. As for the situation in the Netherlands, English is introduced at the primary level for the first time, however, the actual starting age was lowered from 12 to 10 in1986.

Three important events in history paved the way for the development of language education in Austria and these are the fall of the Iron Curtainin 1989, accession process to the European Union in 1995, and the accession of neighboring states to the European Union in 2004. Besides, the teaching of German plays a central role in the development of a coherent language education policy. As a result of all these developments in its history, Austria is one of the pioneering countries in accepting and introducing nation-wide Modern Foreign Language (MFL) learning at primary stage as of the school year 1983 or 1984, and language education was one period perweek, starting from year 3 of primary schools. As of the academic year of 1998 or 1999, MFL learning was determined to start from the first grade of primary school and the transition process was laid down to extend to (and including) 2003 or 2004.

Norway, with its low unemployment rates, high labor market participation –particularly for women- and welfare model, is a full member of amongst others EU's education program through the Agreement on the European Economic Area although it is not a member of the European Union.

Municipalities retain a considerable degree of autonomy in the allocation of resources for primary and lower secondary education.

Compulsory education is for children aged between 6-16 and they attend primary and lower secondary schools in this period. They start learning English systematically at the age of 6. However, an early start in a foreign language does not automatically guarantee higher proficiency levels of English and success in the pupils' attained competence (Muñoz, 2006). Students' exposure to extramural English has a great influence on their higher proficiency levels of English. The topper forming countries in the EF Proficiency Index 2021 provide the opportunity for a large amount of out-of-school contact with English from a young age onwards rather than just an early start for English in school (Peters, 2022).

In addition to these aspects, linguistically closely related languages spoken in these countries facilitates the process of English language learning for students attending compulsory education. In other words, cognate comprehension is the reason of students' improved performance in English in as much as the representations of the mental lexicon are partly overlapping in these languages. All in all, the relationship between an earlier start to language education and language acquisition is not straightforward despite the advantages of young starting ages for language acquisition (Dahl & Vulchanova, 2014). Many studies also draw attention to the fact that the earlier one starts learning a language, the better chances he or she would have in attaining native like target language competence (De Keyser, 2000; Hyltens tam & Abrahamsson, 2003).

In Austrian education system, different forms of assessment are embedded in the education process including pupils' active participation and contributions in class oral assessments, written assessments (tests, written check-ups in the shape of short tests ordictations) and practical assessments. These assessment types indicate that assessment process is extended over a period of time.

Although teachers apply some tests in these courses, they are not standardized and prepared by the language teachers at a certain school.

In the Netherlands, students are not formally tested with a CITO test in the mother tongue and in math's. However, they are not tested in English at the end of the primary level (Drew et al., 2007). As for the assessment of ELT in Singaporean education system, a responsive assessment policy helps language teachers shape reflection, instructional planning, and adaptations to instruction. Additionally, the aim is to help students become selfdirected learners in this process. These responsive learnercentred assessment processes also help teachers differentiate instruction and cater to students' different levels of learning readiness, profiles, and needs (The Ministry of Education, Singapore, 2020). Responsive assessment system is employed to provide evidence of student learning and progress, and shape reflection for instructional planning while helping language learners to become self-directed learners and fostering learner autonomy in this continuum. Formative and summative assessment is not viewed as separate constructs and teachers are urged to use both of them to inform and support the teaching and learning process.

In the Norwegian education system, English language learners have one over all achievement grade for written work and one overall achievement grade for oral th performance in the 10 grade. These oral examinations are generally prepared and assessed locally while the written exam is conducted centrally. It is clear that students' oral communication skills are emphasized rather than solely focusing on the grammatical and syntactic units of language. Students are assessed both formally and informally at a frequency decided by the school and additionally different modes of assessment are employed to serve for formative and summative assessment practices. The documents analyzed in this study indicate that specifications to guide assessment at different year levels aims at aligning assessment with teaching process. All in all, a wide range of assessment modes and tasks are used in these five countries to appropriately match learner needs and this process is designed to address to their readiness levels, interests and learning profiles.

However, in the Turkish EFL context, tensions between the curriculum and assessment practices leads on to a gap between the language teaching policies and actual teaching practices in the classroom.

Additionally, the high stakes tests put pressure on students and these centralized examinations put too much emphasis on reading comprehension and grammar knowledge, which interfere with the process and impede the development of communicative competence. As these tests are crucial in determining students' high school and college enrolment, language teachers feel the need to teach in line with this grammar-based assessment forms. Basok (2017) draw attention to external pressure language teacher's face from administration and the pressure they feel as a result of students' test scores. In the same study, Basok (2017) indicates that elementary school language teachers feel more free to incorporate communicative activities and employ authentic language materials in their courses.

Primary schools are designed to apply the Strategies for English Language Learning and Reading (STELLAR) curriculum in Singapore. STELLAR is an interactive literacy programme that aims at promoting confidence in learning English using children's literature. In the Singapore's EL Syllabus 2020, the integration of skills across all areas of language is promoted in order to achieve coherence and multiple contexts for making and creating meaning in the target language. Students learn English in the multilingual milieu of Singapore. Hence, teachers try to strike a balance between contextualized and holistic approach to English language teaching.

However, in Norway, the number of teaching hours is low, normally less than one per week (Utdanningsdirektoratet, 2006, 2007). As for the role of target language in the curriculum and teaching materials, it is accepted as the object of this process, not as the medium of instruction. The total number of English education hours during compulsory education in Norway is 527 hours. In Netherlands, the total number of hours is 400 hours in this continuum. The common feature of these ELT programs is the importance attributed to the role of multiliteracies and metacognitive strategies in helping students achieve 21st century competencies across all areas of language learning.

As for the English language teaching program is Austria, students generally acquire the language with the help of pervasive English language input in international media and in escapable cultural context in which they live. Additionally, there is a growing tendency to adopt immersion and content-based instruction at the primary level. Austria is a prolific country in developing European Language Portfolio (ELP) models and these models were accredited by the Council of Europe. In line with the necessities of these models, foreign language learning and teaching are accepted as verb in dlicheÜbung, that is, as a compulsory subject without assessment in primary school programs. The number of these courses is the 32 lessons per year at primary stage I (pre-school and primary years 1 and 2). In the other grades, English is taught as an optional subject with no assessment (though it is as an obligatory subject in Vienna) in years 5 to 8, with a total of 80 lessons per year or in some cases, to the extent of one lesson per week. Austrian curricula for foreign language teaching explicitly refer to the recommendation of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe, No. R (98: 6) as regards the levels of competence lay down by CEFR and accordingly language teaching aims at equipping students with an action-oriented foreign language competence. Table 2 shows the starting year of teaching English and English course hours in the countries.

The most noticeable differences between the programs of top-five countries and Turkey are centralized vs. decentralized structures, basic goals of teaching English and perception of language teaching motives. In addition to these points, the inconsistency between the policy and practice stems from language tests and high stakes central exams which have a significant role in the Turkish EFL context. These tests put too much pressure on teachers and language learners in Turkey, and by the same token, language teachers are dissatisfied with the current language assessment practices in Turkish EFL context since these practices hinder teacher and learner autonomy. At this point, it is of great importance to note the term washback effect in testing, and it is defined as the effects of language testing on teaching and learning process (Alderson & Wall, 1993). Özmen (2011) draws attention to the washback effects of these high-stakes tests in his study and reveals that these tests have a negative micro impacton individuals together with a macro impact on a group of test-takers. In a similar study, Yıldırım (2010) concludes that reading, grammar, and vocabulary are overemphasized in English classes of high schools since English Component of the Foreign Language University Entrance Exam attributes a great deal of weight on these three aspects of language. As a result, three of four basic skills are overlooked, and this situation is especially a disadvantage for high school students whose major is English.

English is the primary foreign language to be taught in primary and secondary schools in these five countries and ELT has been prioritized in the last decades with the principles of the Common European Framework of Reference. The possibilities of encountering English outside school are rich in these countries and there are manifold ways and opportunities for language learners to learn and practice English outside the formal educational system. For example, young learners in Denmark are exposed to authentic English language input outside the classroom hours and they generally learn English through their contact with Extramural English although they receive little formal English instruction, two lessons per week for one year. People acknowledge the role of out-ofclass English as a “tool” for learning English, also known as extramural English (Sundqvist, 2009), since many people have access to English daily.

As can be seen from the comparisons made in terms of general educational systems, aims and goals, content, teaching and learning process, and assessment, the integration of four basic language skills is emphasized in Turkey while top-ranking countries in EF Proficiency Index focus on the communicative value and aspect of language. One of the useful ways to understand set backs in our foreign language education system is to analyse the language teaching programs and contexts of countries which are successful in their ELT programs. With this aim in mind, this study canvassed view points and gathered data from the websites of these countries' ministries of education and governments, curriculums, Eurydice and OECD reports, and scholarly studies with regard to language policies and classroom implementations in the setop-ranking five countries. th Turkey, with its ranking as 70 country among 112 countries, has low proficiency in EF Index 2021. Curriculums are prepared centrally by the Ministry of Education in Turkeys of the effects of a centralist structure can be seen in the education system, too. The education systems of these countries are similar in a general sense despite differing aspects and contextual factors.

The centralist system in Turkey creates an obstacle in determining local needs, priorities, problems, and solutions (Kurt, 2006). A partial localization may help to solve problems in ELT and pave the way for improvement and success in English language education. Additionally, micro-level implementation perspectives need to be monitored and assessed effectively to overcome the problems encountered after the completion of macrolevel policy decisions.

As the hybridity and fluidity of English settles the background for variations and linguistic changes, people who use English as a second orlater language are progressively intensifying the stress on the changing status of English in the world rather than its native speakers (Graddol, 2006; Kirkpatrick, 2010). As for unique attributes and strengths that drive these five countries forward in the area of English language proficiency, coherence and stability in English language education are dominant ontological model characteristics in these countries together with their epistemological realism. With the development of English as the foremost global language of communication, educational authorities in these countries made the status of English visible in the national subject curriculum and in the English language practices among language learners. Social constructionist perspectives and these countries' concentrating focus on communicative competence of students are other significant factors contributing to their English proficiency levels. Besides, language learners experience massive exposure to English through audio-visual media, namely with the help of extramural English outside the school settings.

Educational authorities' local beliefs and practices about English language and global circumstances related to the status and place of English in these countries have a reciprocal relationship. Accordingly, these factors have practical long-term implications for the success and future of English language education. ELT stakeholders' knowledge about language beliefs invarious contexts is crucial in preparing appropriate language teaching curricula addressing to the changing needs of time and society. Kramsch (2009), drawing attention to the role of culture and power attributed to higher proficiency levels of English, claims those learners' experiences with learning a new language should be viewed as a subjective experience rather than an instrumental activity to solely get things done. However, the pressure of high stakes tests impede the success of English language learners in Turkey while forming the process into an instrumental activity.

Apart from these aspects, scholarly studies provide evidence of incremental improvements in ELT programs of top-five countries. Frameworks and language learning milieu are the outstanding features of language teaching programs, and these are the points helping students learn to communicate in English and then use English in appropriate contexts.

Despite having a non-official status that is close to second language, English as a school subject has received considerable attention in post-colonial countries like Singapore together with these European countries. Accordingly, learning English and having e certain level of proficiency are considered as a vital life-long skill in these top-ranking countries. English language as a socio –historically situated phenomenon paved the way for the improvement and success in the English language proficiency levels of these countries.

Although this study has shed light on the comparison of high-ranking countries according to the EF Proficiency Index results of 2021, there are some limitations that should be considered in designing further research studies on this topic. As the EF Proficiency Index ranks both low- and high-ranking countries, lower ranking countries can also be analysed in another study. In other words, lowranking countries are beyond the scope of this study, and it could have been another research study to look at the countries that have a lower ranking. To overcome these limitations and provide a broader perspective on the comparison of these countries, further studies can be conducted to compare both low- and high-ranking countries in this context. In another study, the opinions of academics in these countries can also be elicited in order to address the points and English language policy actions mentioned in this study.