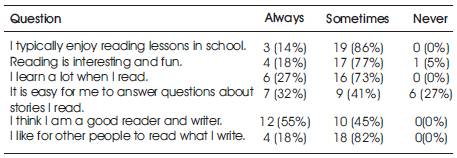

Table 1. Baseline: Number and Percentages of Responses

Literature circles and book clubs have become a popular instructional literacy strategy. In recent years, educators attempt to motivate students to read more in quantity and quality at an early age. A case study design was utilized that required undergraduate education majors to participate in literature circles reading historical fiction and engaging in the literature circle as if they were young children themselves. This engagement included attending weekly meetings with peers, writing in a reflective journal, and partaking in all aspects of a literature circle typically found in intermediate, middle and high school classrooms. A pre and post survey was distributed to one section of an undergraduate course engaged in literature circles, and their journey was documented in a self-reflective journal retained over the semester. Observations were also used to corroborate and triangulate data. Results indicate that literature circles increased university students' engagement with text and commitment to the classroom community.

In an era of diverse classroom settings and standards-based instruction in the U.S., instructors at all levels are searching for strategies that will encourage students to engage with text, develop deeper levels of text comprehension, and stimulate discussion among classmates. Literature circles and other versions of book clubs have been found to increase student enjoyment of and engagement in reading (Fox and Wilkinson, 1997); to expand children's discourse opportunities (Scharer & Peters, 1996); to increase multicultural awareness (Samway & Wang, 1996); to promote other perspectives on social issues (Noll, 1994); to provide social outlets for students (Alvermann, 1996); and to promote gender equity (Evans, Alverman, and Anders, 1998). Additionally, Farris, Nelson and L'Allier (2007) posit the nature of literature circles provides unique opportunities for ELL students to practice and refine their language and literacy skills in authentic situations. The benefits of literature circles are numerous and can be applied across age and grade levels helping to prepare preservice teachers with effective strategies to work with diverse populations.

In Rosenblatt's Reader Response Theory, literature circles are truly a transaction between the text and the reader. Rosenblatt first describe the theory in 1938, the labeled readers as engaging with text and formulating a connection. In 1938 the edition of Literature as Exploration, wrote:

The special meaning and more particularly, the submerged associations that these words and images have for the individual reader will largely determine what the work communicates to him. The reader brings to the work personality traits, memories of past events, present needs and preoccupations, a particular mood of the moment, and a particular physical condition. These and many other elements in a never-to-be-duplicated combination determine his response to the peculiar contribution of the text (pp. 30-31).

Whether educators label engagement with text as literature circles, book clubs, lunch bunch, soup group, or book discussion groups, the reality is that teachers want students to connect with text and bring their experiences, connections, world knowledge, and interpretation to that text. Furthermore, teachers want students to empathize with characters and cultures from varying and diverse backgrounds dissimilar from their own.

Dialog and discussion of text are critical aspects of valuable comprehension instruction (Gambrell & Almasi, 1996). One recommended approach to encourage discussion and dialog in a small group setting is through the implementation of literature circles. Literature circles, popularized by Harvey Daniels (2002), are “small, peer led discussion groups whose members have chosen to read the same story, poem, article or book” (p. 2).When students engage in literature circles, they become reflective and thoughtful readers by developing higher levels of critical thinking and multiple ways to respond to literature while taking part in Grand Conversations (Daniels, 1994; Peterson & Eeds, 1990; Tompkins, 2006; Reutzel & Cooter, 2009). “Grand Conversations about books motivate students to extend, clarify, and elaborate their own interpretations of the text as well as to consider alternative interpretations offered by peers” (Reutzel & Cooter, 2009, p. 191). Furthermore, students express themselves and engage in “an opportunity for enjoyable L2 reading experiences” (Kim, 2004, p. 145), and EFL learners can use English for their own purposes, delving into topics that concern their social worlds (Fredricks, 2012, p. 504). Participation in literature circles is one way to involve, engage and motivate students to read content they may otherwise find difficult or tedious.

Literature circles have great potential to promote reading of historical content because it is an effective strategy that combines cooperative learning environments, shared and independent reading, group discussion, and active participation on many levels. By “engaging students in active reading and writing events, recognizing the collaborative learning offers opportunities to work within students' abilities, engage learning, and provide access to literacy materials and events” (Casey, 2008, p. 284) students take ownership of learning.

The first key ingredients of literature circles is the powerful element of cooperative learning environments. Zemelman, Daniels, and Hyde (1993) consider cooperative learning as an effective educational practice since it has the high probability of engaging students on many different levels. Cooperative learning instruction “encourage(s) students to discuss, debate, disagree, and ultimately teach one another” (Slavin, 1995, p. 7). The combination of cooperative learning with literature circles promotes collaboration, active participation, and responsibility because students are encouraged to collaborate and work with peers to assign reading and group roles in addition to completing assignments related to the text. Active and engaged participation is unavoidable as students discuss portions of text, share passages and vocabulary, question the author, make connections, and reflect on text. Finally, literature circles require all students to take responsibility for their own learning, and the small group size encourages accountability for all students to perform their part and serve as a member of a collaborative learning environment.

A second key ingredient of literature circles is the promotion of independent reading, which research indicates the single factor most strongly associated with reading achievement (Anderson, Wilson & Fielding, 1988). Literature circles gives students the freedom to read self-selected material at their own pace, which is an essential component to encourage and promote sustained silent reading and independent reading. By giving students their choice of reading, the likelihood that students will read the text is greater. Literature circles also engages readers for many different reasons and on various levels. Students engage with text because they have the opportunity to make choices, participate, and take ownership of their own learning while sharing responsibility for that learning with peers (Casey, 2008; Guthrie& Cox , 2001). “Engaged readers are those who are motivated by the material, use multiple strategies to ensure comprehension, and are able to construct new knowledge” (Casey, 2008, p. 286).

The third key ingredient of literature circles is the opportunity for group discussion. Vygotsky (1978) theorized that environments that are social in nature provide students with the opportunity to observe higher levels of cognitive processing. With that said, literature circles serve as social and academic settings where students actively constructed knowledge through oral discourse. This oral discourse provides students with opportunities to learn through observation of others and engagement with others. These social environments allow students to interact naturally in a small group that provide comfort and confidentiality. These meetings afford readers a chance to respond to literature in cognitive and affective ways and ultimately promote life-long learning. The classroom climate had the potential to improve greatly because students were given the opportunity to work in decision making in accordance with their needs and interests (Burns, 1998). Kong & Fitch (2003) note that literature circles teach readers how to respond to reading and engage in conversation about text. The students who may not know how to talk about text can learn this valuable skill through peer modeling and collaborative discussion. Furthermore, Vygotsky (1978) theorize that effective learning takes place when learners recognize their own needs and are in charge of their own leaning in collaboration with peers. Literature circles naturally allow ownership and collaboration to occur.

The final factor affecting students' literacy skills is the concept of self-efficacy. An element of Bandura's cognitive theory is the idea of howan individual views performance on a certain task. Bandura identified self-efficacy as one of the critical factors motivating people to engage in pursuing their goals.

The purpose of the semester-long project was to create a “new context where discussion among members becomes the event within which the transactional sharing and listening of multiple ideas continually shapes and reshapes meaning” (Certo, Moxley, Reffitt, & Miller, 2010, p. 244). Meaning-making occurs in two interdependent venues; the reader interprets with the first interaction with the text, and then meaning may morph and change when the engagement and discussion with co-readers occurs (Gee, 2001; Lave & Wenger, 1991; Rosenblatt, 1938). In this study, literature circles were used with preservice teachers enrolled in a small, private university as they prepared to become elementary classroom teachers. The goals of the university literature circles were to encourage social interaction, help students connect with text, increase preservice teachers' historical content knowledge, and improve students' reading self-efficacy.

The research designed utilized the case of study pre/post surveys, observations, and reflective journals. Qualitative data allows for researchers to gain insight into the problems teachers face in their classrooms (Creswell, 2005). Case study design is derived from the paradigm of constructivism that recognizes the importance of the participants' and researcher's subjective interpretive lens. Additionally, case study research emphasizing the 'case' that is not too broad in scope. Miles and Huberman (1994) define a case as, “a phenomenon of some sort occurring in a bounded context, in effect, your unit of analysis” (p. 25).

Participants consists of 22 preservice teachers (20 female, 2 male) enrolled in a 15 week education course from a small, private university in western Pennsylvania. Participants ranged in age from 20-35. Participants selected an adolescent historical fiction book to read based on interest.

Data was triangulated by collecting data from three data sources; a self-constructed Reading Attitude Survey, weekly observations, and participants' weekly reflective journals. Participants completed a Reading Attitude Survey developed by the instructor before and after the implementation of literature circles. The survey was a Likert Scale consisting of three levels; always, sometimes and never. Additionally, the instructor observed students as they met weekly in their literature circles. Participants were also required to write in a reflective weekly journal about their participation in the literature circle.

The first day of the semester, the instructor introduced the concept of literature circles and introduced each book selection by giving a book talk to the participants. The book talks highlighted information about the author, characters, plot, and time period. Students whom previously read the books also offered their opinions about the books. Additionally, students were encouraged to conduct additional research about the book and/or time period. The titles included: Elijah of Buxton by Christopher Paul Curtis, Copper Sun by Sharon Draper, Fallen Angels by Walter Dean Myers, and The Boy in the Striped Pajamas by John Boyne. The titles were chosen for a myriad of reasons. First, three titles were Coretta Scott King Award winners making them likely texts used in today's classrooms as well as quality literature written by African American authors. Second, all texts possess strong historical lessons that are part of U.S. curriculums. Furthermore, the use of these historical novels could be easily tied to standards at the state and national levels as well as the Common Core Standards. Finally, the characters in the books are ones with which the instructor was certain students would connect on some level. Literature discussion groups were scheduled to meet seven times over the course of the semester. Each meeting/session students were required to perform a job. The job titles, based on the work of Daniels (1994),included: Discussion Starter, Illustrator/Visual Literacy, Word Wizard/Vocabulary Enhancer/Passage Picker, Summarizer, and Connector.

The members of the literature circle were responsible for setting the pace of the reading, assigning jobs/roles, completing pre-discussion and post discussion logs, and a final project, which included a curriculum map, extension project and applicable assessment tools. Additionally, a reflective journal was kept by students where they were required to document their feelings and attitudes about their participation in the literature circle.

Overall, the assignment demonstrated that literature circles are successful in engaging students in discussion, dialog, and historical content while promoting a positive reading attitude that improves students' reading self-efficacy. One student wrote,

There is no way I would have read a book about the Vietnam War (Fallen Angels by Walter Dean Myers) on my own. Now, not only do I seek to read more in quantity, I strive to read more often. The literature discussion group made me realize that a teacher's love of literacy can and does transfer to students, no matter the age of the students (Brian).

Table 1 indicates the survey responses before literature circles (Baseline) were implemented, and Table 2 indicates the survey responses after literature circles (Post Treatment) were implemented.

Table 1. Baseline: Number and Percentages of Responses

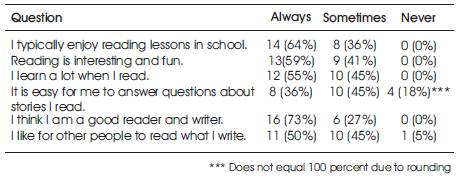

Table 2. Post Treatment: Number and Percentages of Responses

Post data indicates that students improved in their attitude toward reading, found reading to be more interesting, took ownership of their learning, improved in their writing attitudes, and improved their reading self-efficacy. According to May (1998) literature circles offer students inspiration, aesthetic experiences and social cohesion. Students were provided with a text and a situation, the rest was their responsibility. Students created a climate of acceptability, responsibility, and interaction. Small group discussion and engagement could attribute to the reason students found reading more interesting after the implementation of literature circles. Barnes and Todd (1977) found great value in small group interactions and discussion because it essentially supports participants' abilities to negotiate meaning and come to a new way of understanding. Equal participation occurs when participants are provided with opportunities to enact collaborative responsibilities (Cazden, 2001). For students enrolled in a teacher education program, participation in literature circles provided a concrete, practical example of how to effectively integrate trade books into the content area while meeting state and national standards across the curriculum. The use of literature circles also provided students with a model for content area reading pedagogy. By requiring preservice teachers to participate in assignments in which their future students may also engage, the authenticity of the assignment had the potential to resonate more deeply with candidates as opposed to a required reading without applicability. One student remarked in her reflective journal,

I've never been so involved in a book before in my life. Young adult literature has opened my eyes to so much allowing me to make connections on so many levels, both literature-based and content-based. I never thought I'd be changed by Copper Sun. (Stacey)

Students responded that ownership and accountability played a significant role in the improvement in their reading attitudes. One student wrote, “I'm amazed at how much I've learned from my reading. I think this is because I picked the book that I knew I would be most interested in reading while being responsible to my group members.” Additionally, literature circles required students to engage in extensive preparation for, and involvement in, discussion. This emphasis on oral language and preparation for discussion may have helped students better answer questions about text which in turn may have contributed to increased comprehension. Consequently, students may have found that the small-group dynamic provided the opportunity to listen to others more intently and thus added to their understanding of the text. For many students, the necessary scaffolding, intentional and strategic support (Vygotsky, 1978; Wood, Bruner, & Ross, 1976) for this unfamiliar task was necessary. To scaffold appropriately, teachers determine what kind and how much help or information is needed for each learner to assist as they internalize skills needed for independent performance later (Ukrainetz, 2006). The group dynamic and collaboration with both instructor and peers may have filled this void.

Students were also very receptive to the self-selection of texts. Gambrell and Almasi (1996) suggest students should be given choice when selecting books for independent reading. “The research related to self-selection of reading materials supports the notion that the books and stories that children find 'most interesting' are those they have selected for their own reasons and purposes” (p. 21). A college senior agreed that the power of choice was important for this assignment.

It was refreshing to be able to pick a book I wanted to read for a college class that never happens. After the book talk, I became very interested in reading Fallen Angels by Walter Dean Myers since my father and uncle were in Vietnam. I thought I could better understand their experience by reading this book

Reading and writing self-efficacy improved slightly at the conclusion of the literature discussion groups. Because “human beings derive satisfaction from using both their innate and acquired abilities” (Bigge & Shermis, 1999, p. 2), students who believe they are poor readers often report being unable to read or comprehend class material. In this study, students were able to learn from their peers, discuss confusing parts of the text, and engage with texts in new and different ways. These interactions helped support students, and their attitudes toward their own learning improved. One student wrote,

I totally hate to read. I would never pick up a book and read for pleasure.

Usually I would buy the Spark notes for a class. In this situation, I knew I was responsible and had to read or my group members would be upset. I feel better about my ability to read because my peers helped me better understand the material. Talking about what I read helped me understand it. (Angel)

McCarthy, Meier, Rinderer (1985) report that self-efficacy, which is expressed as a situation and subject-specific personal confidence in one's ability to successfully perform tasks at a given level, is a strong predictor of ability. The demands of participation in the literature circle community may have assisted in the increase in students' reading self-efficacy.

Classroom community may be the one element students enjoyed most. Shaffer and Anunden (1993) define classroom community as "a dynamic whole that emerges when a group: (a) participates in common practices; (b) depends upon one another; (c) makes decisions together; (d) identifies themselves as part of something larger than the sum of their individual relationships; and (e) commits themselves to their own, one another's and the groups' well being" (p.3). The literature circle provided students with the group dynamic commonly missing in college classrooms. Students were required, by design, to depend on one another, make decisions as a group, and finally, commit to the literature circle's well being. Without an individual's participation, the group could not flourish or succeed in meeting the outcomes and expectations of the course. Christina wrote:

We became really close over the semester. I found myself with new friends, but in an educational setting. It was refreshing to come to class and talk with peers about what we read. Usually, you come to class to talk about things you do outside of class. This was a blast for me and gave me a chance to learn from my classmates. We rarely get to do that in college.(Christina)

Although students involved in this particular study were adults and considered competent and strategic readers, implementation of literature circles with elementary, middle or high school students may pose obstacles that should be carefully considered. Allowing children to decide which book they want to read may not be feasible due to ability and/or reading levels, group dynamics, availability of materials, and time management. The solution may be to offer second titles from a particular time period on varying reading levels. Working with college students afforded the instructor some flexibility in that regard. Time management proved to be one obstacle during this particular study when students were engrossed in frank discussion. Giving students a warning signal could potentially lessen this burden.

One challenge of literature circles with younger students may be accountability and attendance. At the university level, students were aware of the gravity of missing class or not fulfilling their required task. Teachers of younger children may find that students missing class, not completing the required reading or lack of participation could potentially detract from the intention of literature circles. To alleviate this difficulty with younger children, constant and consistent group monitoring is essential as an informal assessment tool as well as communication with parents about the importance of their child's participation.

As with any instructional strategy, modeling by instructors and classroom teachers is an essential component of literature circles. Demonstrating how to actively engage in conversation and serve as a contributing member of the group can go a long way in avoiding potential problems. Mastery of all the skills necessary to participate in a literature circle is not the ultimate goal; the goal is to illustrate for students that comprehension of text is social and talking about text is an acceptable means to gain a deeper appreciation for literature of many genres.

The instructor required students to participate in literature circles and write in a reflective journal per course requirements. Although surveys were anonymous, students may have felt obligated to respond in a certain way. Additionally, since all students were required to take the course for certification, students may have been highly motivated to succeed and thus contributed to the overall success. Finally, the instructor was an active participant in all literature circles as often as possible. Students' optimism could be conceived as a teacher pleasing behavior.

Students found multiple ways to connect with the text as evidenced by their reflective journal entries. Students' exceptionalities and differences can be celebrated because differentiated instruction is naturally built into the system. Students are permitted to use their strengths to succeed in ways that fit their learning styles. A student who is artistic finds comfort in performing a job that allows to interpret the text through pictures. Moreover, Dryer and Horowitz (1997) found that learners are more satisfied with their interactions when their group members have similar goals. A literature circle provides the goal, but the learners decide how that goal will be accomplished. The common goal of the group contributes to all members feeling successful at the task completion. The commonality of learning and reading together gives all members a sense of “togetherness” or “community” and a sense of responsibility to a group. Overall, the literature circle can teach tolerance, responsibility, and problem solving; life skills that will help future educators survive in the work place. Moreover, literature circles can aid in comprehension of text, improve reading self-efficacy, and potentially help withdrawn students or reluctant readers open up and engage in conversation and share their work.

As future educators, pre-service teachers must see the importance of modeling. Reading must be a priority in the classroom where teachers display their love of books through actions and not words alone. Teachers reading the same texts as students open many doors both educationally and personally. To sit with a group of students and discuss books can be an eye-opening experience—one that taught the instructor so much about students. The instructor learned abundantly about students' family backgrounds, personal beliefs, and reading difficulties. The instructor learned that interpretation of text comes in many packages and talking about text is one of the best ways to comprehend what is read. The instructor also learned that when students study together, personal bonds are formed and it can significantly improve the classroom community. Members of literature circles discuss their inner-most thoughts without judgment from others and potentially even the playing field academically. Finally, engaging in book discussions with students taught the instructor that text can bring people together for a common goal, improve relationships, and ultimately improve learner outcomes.

Students have read about book discussion groups and literature circles in many of their education textbooks, but this assignment took the theoretical and made it practical and applicable. Students learned how easily book discussion groups could be implemented into their own future classrooms with little effort while immersing students in content and quality literature. Additionally, students learned the importance of instructors sitting with students, discussing literature, and engaging with text. Students discussed vocabulary, parts that were unclear, author's intentions, and provocative passages. Students quickly realized the importance of talking about and engaging with text on many different levels. Most importantly, students learned the literature circles really became a small community within the classroom. Students had to learn to negotiate social interactions. The small group atmosphere became an intimate circle of discovery. Samway and Whang (1996) found that students who feel comfortable socially will begin to share ideas in the classroom. The literature circles provided a social and academic safe-haven for those who might not participate in larger classroom discussions.