Figure 1. CARS model for article introductions Swales and F1eak (994.

Graduate students submit academic papers at the end of the term as part of their coursework. Such papers contain introduction moves which may be troublesome and conclusion moves which may contain sub-moves not really required. This paper is aimed at assessing what particular moves are employed in the introduction and conclusion sections of 21 graduate research papers submitted in one leading university in Manila. Ten of these were written by MA students while 11 were written by Ph.D. students. The study employed the framework proposed by Swales and Feak (1994) pertaining to moves in research paper introductions and Yang and Allison's (2003)framework for analyzing the conclusion section.

Findings revealed that in the introduction section, all MA and PhD students employed Move 1 with majority employing 2-3 sub-moves. With regard to Move 2, 10 of the 21 papers employed the sub-move Indicating a gap; three employed the sub-move Counter-claiming; the rest did not employ any sub-move at all. With respect to Move 3, results showed that the most commonly used sub-moves were Outlining purposes and Announcing present research. Finally with regard to the conclusion section, most writers employed Moves 1, 3 and 2, in that order. However, the sub-move evaluating methodology was not at all utilized as part of Move 2.

Graduate students submit academic papers at the end of the term as part of their course requirements. Such papers include introduction moves which may be troublesome for some of them. It has been said that writing the introduction is one of the most difficult tasks in preparing an academic paper. In fact, some writing teachers claim that only after one writes the methodology and the results sections of an academic paper can one have sufficient thoughts to write about in the introduction as the completed analysis of the data will now make it easier to write this section. In other words, an academic paper given shape makes it easier for the writer to acquaint the readers with the content of the material rather than projecting what may or may not happen when no research procedure has not yet been carried out or even initiated in the first place.

An even more challenging task both for the writing teacher and the writing student is to be able to identify moves in the different sections of an academic paper which can be discipline-specific. One discipline, for instance, employs a different set of discourse or organizational moves entirely different from another discipline. It is difficult to position oneself in the academic/professional community in terms of establishing a standard discourse structure particularly when what is most crucial to the task of writing is getting one's paper published in an academic journal of international and scholarly reputation. As non-native speakers of English, Filipino writers of research articles may not find it easy to participate in international academic research as certain conventions are also imposed by specific discourse communities.

With respect to move sequences in the conclusion section, certain impediments are likewise encountered by nonnative users of English particularly in the use of sub-moves that may not necessarily be present but just the same, are employed by non-English users For instance, some conclusion sections may be found to include recommendations as well as implications for second language teaching and learning or implications for classroom teaching and learning. At times, the label “pedagogical implications” is used. Considering the expectations of the journal's readership, those submitting research articles for possible publication include a paragraph or so, on implications for teaching and learning subsumed under conclusion or a separate section on this. Han (2007) claims that the practice of devoting a section in any research article to pedagogical implications might have stemmed from a fallacy that any research can be related to pedagogy (p. 391). Such claim is corroborated by Ellis (2005 as cited in Han (2007) when he states that SLA is still a very young field of study”, and for that reason alone, any excessive concern to allege or show a relationship between an empirical study and classroom practice may be counterproductive to research and practice (p. 391).

Bhatia (1993)states that although a writer has much freedom to use linguistic resources in any way she/he likes, s/he must conform to certain standard practices within the boundaries of a particular genre. He also claims that it is possible for a specialist to exploit the rules and conventions of a genre in order to achieve special effects or private intentions, as it were, but she/he cannot break away from such constraints completely without being noticeably odd (p. 14). Bhatia moves on by saying that there are also restrictions operating on the intent, positioning and internal structure of the genre within a particular professional or academic context but that it is certain that one can only exploit the conventions of the genre when s/he is familiar with them (p. 15).

Studies show that findings as regards organizational moves vary with regard to research articles. Samraj (2008)reveals that the structure of introductions in dissertations in biology, philosophy, and linguistics employ discourse features that distinguish this genre from research articles. Moreover, first person pronoun in the introductions shows that philosophy students create a much stronger authorial presence but establish weaker intertextual links to previous research than the biology students. It is in this part that the writers present their contributions to knowledge. In contrast, linguistics students occupy a more central position in terms of this scope. The use of the first person pronoun is also found as a variable in establishing authorial presence (Hyland, 2001 as cited in Samraj (2008). Such discourse feature is used for the following reasons by research article writers: (i) to state the goal or purpose of the paper, (ii) to outline procedures carried out, and (iii) to make a knowledge claim (Harwood, 2005; Hyland, 2001; Kuo, 1999 as cited in Samraj (2008).

Ahmad (1997 as cited in Peacock, (2002) employed Swales' model to analyze the introductions of 20 Malay research articles. It was found that 35% did not have the move common in introductions written in English. Duszak (1994 as cited in Peacock, (2002)studied 40 introductions and found out some differences in terms of move structure. With this result, she assumed that non-native speakers may “transmit discoursal patterns typical of their own tongue but alien to English” which was corroborated by Golebiowski (1998; 1999 as cited in Peacock, (2002). Using Swales' model, she analyzed 18 Psychology research articles, 8 in Polish and 10 by Polish authors in English, leading her to hypothesize that Polish authors writing in English preserve their native style(p. 482).

Peacock, (2002)describes an analysis of communicative moves in discussion sections across seven disciplines - Physics, Biology, Environmental Science, Business, Language and Linguistics, Public and Social Administration, and Law. The writer claims that while more and more studies are conducted on introductions in academic writing, less research focused on the organizational moves of discussion sections as well as the variations in writing between native and non-native speakers or users of English. On the micro-level, Peacock also notes that the assessment of obligatory and optional moves and cycles is likewise essential along with the optimal order of moves. Such has implications on the teaching of writing particularly, the need to teach discipline-specific research writing as well as its implications on ESP.

With respect to the conclusion section, Yang and Allison (2003)cited three organizational moves employed in research articles in applied linguistics as writers move from the results to the conclusion section. The three-move structure is as follows :

Move 1: Summarizing the study

Move 2: Evaluating the study

Move 3: Deductions from the research

While Yang and Allison note that there are similarities in the moves of the Discussion and Conclusion sections, they differ in terms of the existence of Moves 1-4 which in turn reflects differences in overall functional weightings of each section. While the Discussion section focuses more on commenting on specific results, the Conclusion section emphasizes more the overall results and evaluation on the study. Moreover, it is to be noted that Move 2 also touches on indicating the significance, advantage, limitations of the study as well as evaluating methodology while Move 3 recommends further research and draws pedagogical implications.

Yang and Allison further added that the main purpose of a Conclusion is to summarize the research by highlighting the findings, identifying possible areas for future research and providing pedagogical implications.

On the other hand, Dudley-Evans (1994)claimed that moves in research articles' discussion section can be summed up into three sections (Introduction, Evaluation, Conclusion) with the corresponding move cycles.

1. Background information

2. Statement of result

3. Finding

4. (Un)expected outcome

5. Reference to previous research

6. Explanation

7. Claim

8. Limitation

9. Recommendation

Of these, he believes that the findings move and reference to previous research moves are truly significant

| Move 1: | Background information or |

| Moves 1/5: | Background information and Reference to previous research |

| Move 2/3: | Statement of result/finding |

| Moves 2/3 5: | Satement of result/finding and Reference to previous research |

| Moves 7 5: | Claim and Reference to previous research |

| Moves 5 | Reference to previous research and Claim |

| Moves 3&7: | Finding and Claim |

| Move 9 | Recommendation for future research |

Reacting to the model proposed by Dudley-Evans, Peacock (2002)suggests that the model be revised. From a nine-move sequence, Peacock now recommends an eight-move sequence which no longer includes the second (statement of result).

1. Background information

2. Finding

3. Expected or Unexpected outcome

4. Reference to previous research

5. Explanation

6. Claim

7. Limitation

8. Recommendation

The statement of result is now merged with the finding move which is similar to a statement of result but this time with or without reference to a graph or table. Moreover, the third move, unexpected outcome, now states unexpected and expected outcome which comments on whether the result is something expected or not.

With these modifications, the three-part framework is now represented as follows:

| Move 1/2/6: | Background Information/Finding/Claim |

| Key Moves: | Moves 2;4/2&6/3;4/3;5: Finding and Reference to a previous research/Finding and Claim Expected or unexpected outcome and Reference to a previous research Expected or unexpected outcome and Explanation |

Less Common Move Cycles: Moves 6&4/4&6: Claim and Reference to a previous research

Reference to a previous research and claim

| Moves 2&6/8: | Finding and Claim/Recommendation |

| Moves 8&6: | Recommendation and Claim |

| Moves 7&6: | Limitation and Claim |

Swales (1990)then makes an account of the studies done on a macro-level that analyzed the structure of research articles. He cites Stanley (1984) who proposed a problemsolution structure, Bruce (1983) who noted that the Introduction-Method-Results-Discussion (IRMD) format follows the logical cycle of inductive inquiry as well as Hutchins (1977) who offered a modification on Kinneavy's cycle of Dogma-Dissonance-Crisis-Search-New Model of the research article.

With all these studies conducted on the move sequences of research articles, Bhatia (1993)leaves a number of significant questions which remain to be unanswered.

Is this true to all the genres in a particular variety? How do these linguistic features realize social realities in a particular field of study or profession? Why do the users of the genre use these features and not others? Does the use of these features represent specific conventions in a particular genre, and if they do, what happens if some practitioners take liberties with these conventions? (p. 18).

While it is true that many studies have already been conducted on the moves employed in research articles, it is still worth noting that more studies should still be conducted on this particular genre so that issues on second language teaching and writing could be addressed, including those pertaining to ESP and academic writing. The author take the position of Bhatia (1993)who underscored the importance of knowing why some writers use certain features and others not and if such features do represent certain conventions observed by those belonging to such discipline.

As an academic writing teacher in the graduate level, the author believe that while graduate students come from a broad range of disciplines, they still need to employ academic writing in their writing outputs. It is in this light that this paper has been conceptualized. It is aimed at assessing what particular moves are employed in the introduction and conclusion sections of the research papers submitted by graduate students in the English Language program in compliance with their course work.

This study is then conducted with the hope of finding answers to the following research questions.

In analyzing the discourse structure of introduction in the academic papers, the study employed the framework proposed by Swales and F1eak (994 pertaining to moves in research paper introductions. Note that Swales in 1981b, 1985, 1990 presented a four-move structure for research paper introductions.

However, Swales and F1eak (994 revised the said moves and reduced the four-move structure into a three-move structure with the corresponding sub-moves and called it the CARS model (Create a Research Space)(Figure 1)

Moves 1 and 2 in the original model were merged as it is difficult to cite the difference between Moves 1 (Establishing field) and 2 (Summarizing previous research) according to Swales).

With regard to the analysis of the first person pronoun, the study simply analyzed the frequency of occurrence of the first person pronoun as well as the location of these pronouns in the moves employed in the introduction and conclusion sections

Finally, the author employed the framework of Yang and Allison (2003) in analyzing the conclusion moves. The discourse structure was then analyzed based on the three move scheme.

Introduction and conclusion moves were identified by the researcher and two inter-coders who were both Ph.D. students were invited to help validate the researcher's findings. All 21 papers were reviewed by both coders. Research papers submitted by graduate students in AYs 2009-2010 and 2010-2011 served as corpus of the study.

One aspect of research paper writing that some student- writers find difficult to engage in is the writing of the introduction. In fact, this sometimes happens even if the data are readily available. Groping in the dark has become an ordinar y expectation when writing introductions. Generating ideas and sequencing one's thoughts take some time and in some instances, writers skip this section and move on to writing other sections or subsections first. As mentioned earlier in this paper, it poses less difficulty on some writers when they write the introduction part only after the Review of Related Literature has been written and/or the analysis of the data completed.

In academic writing, certain moves are required to observe a smooth transition of ideas in the paper. However, not all writers recognize the importance of such moves and therefore, consciously or unconsciously skip some of them.

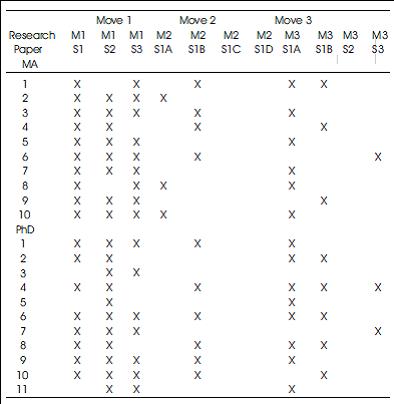

Table 1 shows the move sequences in the introduction section present in the papers analyzed:

Table 1. Move Sequences in the Introduction Section of Academic Papers Written by MA/PhD Students

| Move1 (M1): | Establishing a Territory |

| Step1 (S1): | Claiming centrality and/or |

| Step 2 (S2): | Making topic generalization(s) and/or |

| Step 3 (S3): | Reviewing items of previous research |

| Move 2 (M2): | Establishing a Niche |

| Step 1A (S1A): | Claiming centrality and/or |

| Step 1B (S1B): | Indicating a gap or |

| Step 1C (S1C): | Question-raising or |

| Step 1D (S1D): | Occupying a niche |

| Step 1A(S1A): | Outlining purposes |

| Step 1B (S1B): | Announcing present research |

| Step 2 (S2): | Announcing principal findings |

| Step 3 (S3): | Indicating RA structure |

Findings reveal that all MA and PhD students employ Move 1 (Establishing a Territory). Differences, however, are spotted in terms of the steps or sub-moves used. For instance, all steps involved in Move 1 were present in at least six of the 10 MA papers while four employed two out of the three submoves. With regard to the PhD papers, five of the 11 employed all three sub-moves, five employed two out of the three sub-moves and one used only one sub-move. It then appears that while Swales and Feak give options to the writers to employ all steps or sub-moves or any of the three steps, majority of the writers used more than one step in Move 1. It appears that graduate student-writers do find the steps necessary to establishing a strong territory and thus, the need to employ at least two steps for Move 1.

An example of an MA text which employed all the steps in Move 1 is found below

One important goal of language teaching is to develop the communicative competence of learners. Whenever language is addressed in the English classroom, problems regarding the use of language in communication among students are experienced by both language and content area teachers whether in written or oral form. In particular, teachers do recognize the difficulty of students expressing themselves orally in English. It has been observed among learners that when they are asked to explain, discuss, converse or ask questions in English, communication breaks down or in most cases, learners stop speaking because they do not know what to say. In other words, learners exhibit limitations in oral communication. One reason for this is that second language (L2) learners attempt to use a language which is not their own. They encounter an experience different from those who think and speak in the first language. Hence, unlike L1 children, L2 learners are always wanting to express things for which they do not have the means in the second language (Cook, 1996: 67). (M1 S2) To cope with this demand, L2 learners need compensatory strategies which they may employ to be able to proceed in a communicative situation.

Oxford (1990) popularized the most complete listing of language learning strategies employed by language learners. There are two main types of these language learning strategies: the direct strategies that involve language directly and the indirect strategies that do not involve language directly. Among the direct strategies are compensatory strategies that “enable learners to use the new language for either comprehension or production despite limitations in knowledge(p.47).

The following are the different compensatory strategies mentioned by Oxford (1990)

Several studies conducted regarding frequency of compensatory strategies and their relation to oral communication are worth mentioning. For instance, with regard to the frequency of compensatory strategies, Tarone's (1977) study revealed that the most frequently used was circumlocution. Another study that Tarone conducted was on the success of communication strategies for listeners, revealing that word coinage was the most successful. In relation to oral tasks, Flyman (1997) investigated the type of compensatory strategies employed in three potential oral tasks in the classroom and the role these strategies play in language acquisition. As regards the role of strategy in language learning, Lujan (2003) found that linguistic strategies enable the learners to manipulate the linguistic knowledge available to them and that task requirements strongly influence the use of strategies. In addition, Ogeyik (2009) investigated the strategy used by learners in speaking and writing as well as how learners employ strategies in language use.

Below is an example of a PhD text which employed all the steps in Move 1.

Politics is a constant topic of interest in almost all parts of the globe. Political issues never escape the meticulously prying lens of local and international media – print, broadcast, or online. People from practically all walks of life have their own unflinching stance for every political controversy, political scandal, and anomalous affair of the state. Both public and private sectors may directly or indirectly articulate their resistance or concurrence to every decision, pronouncement, and action of the government in power.

Interestingly, political noise becomes more fascinating and intriguing to the public because of political wannabes and prominent political figures who occupy higher and topmost positions in the local and national legislative hierarchy. In the Philippines, for example, these personalities are often regarded distinguished reputable, public servants, and well-educated notwithstanding the incessant controversies attached to their names. In addition, a majority of these public figures maintain a reputation of being eloquent and notable talking heads or rhetoricians since it is likely that they possess a certain level of verbal artistry and linguistic sophistication, have mastered the intricate art of argumentation, and communicate with extreme convincing power to attract the electorate.

Equally amusing is the fact that in potential interpersonal friction and confrontations and relational conflicts, their ability to manipulate the language in varied communication milieus is the same acumen they employ to steer away from situations that threaten their 'face' or the public image that a person claims for himself (Lim & Bowers, 1991). Most of them are endowed with the rare skills of dissociating themselves from dreadfully unpleasant and politically risky situations, and to constantly project a positive self-image. Hence, at times, when they verbalize their intents, they are often heard offering vaguely-worded, verbally opaque, and indirect responses to tough questions. As how Kuo (2003) aptly puts it, “… political figures tend to communicate in vague and indirect ways to protect and further their own careers and to gain both political and interactional advantages over their political opponents” (p. 1). Put more succinctly, they use obliqueness as a strategy to save themselves from face threatening circumstances. Obeng (1997) clearly explains this by arguing that “The obliqueness and/or abstinence from candor, gives them a form of protection or communicational immunity and immunity from prosecution” (p.1). Thus, whether one agrees or not, vagueness or indirectness has become a defining trait of political language (Gruber 1993) and extremely prevalent particularly in oral discourses.

With respect to Move 2 (Establishing a Niche), while some writers employed this move, they employed only one step. In fact, only seven of the 10 found the need to employ either Counter-claiming (Step 1A) or Indicating a gap (Step1B) while six of the 11 PhD papers reviewed employed only one sub-move which is Indicating a gap (Step 1B). The rest did not employ Move 2 at all. All writers did not find the need to employ Question-raising (Step 1C) and Continuing a tradition (Step 1D).

The following paragraphs are sample texts which use Move 2 Step 1B (Indicating a gap) immediately after Move 1 Step 3

Oxford (1990) popularized the most complete listing of language learning strategies employed by language learners. There are two main types of these language learning strategies: the direct strategies that involve language directly and the indirect strategies that do not involve language directly. Among the direct strategies are compensatory strategies that “enable learners to use the new language for either comprehension or production despite limitations in knowledge” (p.47).

The following are the different compensatory strategies mentioned by Oxford (1990).

Several studies conducted regarding frequency of compensatory strategies and their relation to oral communication are worth mentioning. For instance, with regard to the frequency of compensatory strategies, Tarone's (1977) study revealed that the most frequently used was circumlocution. Another study that Tarone conducted was on the success of communication strategies for listeners, revealing that word coinage was the most successful. In relation to oral tasks, Flyman (1997) investigated the type of compensatory strategies employed in three potential oral tasks in the classroom and the role these strategies play in language acquisition. As regards the role of strategy in language learning, Lujan (2003) found that linguistic strategies enable the learners to manipulate the linguistic knowledge available to them and that task requirements strongly influence the use of strategies. In addition, Ogeyik (2009) investigated the strategy used by the learners in speaking and writing as well as how learners employ strategies in language use. (M2S1B) Though these studies present significant findings, they restricted their scope on the frequency of the strategies and the role of the strategies play in language acquisition.

Equally amusing is the fact that in potential interpersonal friction and confrontations and relational conflicts, their ability to manipulate the language in varied communication milieus is the same acumen they employ to steer away from situations that threaten their 'face' or the public image that a person claims for himself (Lim & Bowers, 1991). Most of them are endowed with the rare skills of dissociating themselves from dreadfully unpleasant and politically risky situations, and to constantly project a positive self-image. Hence, at times, when they verbalize their intents, they are often heard offering vaguely-worded, verbally opaque, and indirect responses to tough questions. As how Kuo (2003) aptly puts it, “… political figures tend to communicate in vague and indirect ways to protect and further their own careers and to gain both political and interactional advantages over their political opponents” (p. 1). Put more succinctly, they use obliqueness as a strategy to save themselves from face threatening circumstances. Obeng (1997) clearly explains this by arguing that “The obliqueness and/or abstinence from candor, gives them a form of protection or communicational immunity and immunity from prosecution” (p.1). Thus, whether one agrees or not, vagueness or indirectness has become a defining trait of political language (Gruber 1993) and extremely prevalent particularly in oral discourses.

In Philippine radio and television broadcasts, e.g. informal, formal, and ambush interviews, debates, media appearances, and senate or congress investigations, eminent Filipino politicians are often suspected of evading challenging questions. This, however, has so far been formally investigated.

It has been noted that eight out of the 10 MA papers employed Move 3 (Occupying a niche) either utilizing Step 1A (Outlining purposes) or Step 1B (Announcing present research). Similarly, only two of the 11 PhD papers did not use at all Move 3. However, while the MA papers chose between Step 1A and Step 1B, five of the PhD papers reviewed employed both steps even if Swales and Feak endorse the use of either of the two steps. What is striking though is the fact that not one of the 21 papers reviewed found the need to employ Step 2 in Move 3 (Announcing principal findings) as well as Step 3 (Indicating RA Structure) which was employed in only three of the papers reviewed.

Below are sample texts which employed Move 3 Step 1A (Outlining purposes) immediately after Move 2 Step 1B.

Though these studies present significant findings, they restricted their scope on the frequency of the strategies and the role the strategies play in language acquisition. (M3 S1A) Hence, the present study primarily focuses on the use of compensatory strategies and their relationship to such variables namely: program enrolled in, school graduated from in high school, language at home and grade in English 1, variables which were not at all investigated in previous studies conducted.

In Philippine radio and television broadcasts, e.g. informal, formal, and ambush interviews, debates, media appearances, and senate or congress investigations, eminent Filipino politicians are often suspected of evading challenging questions. This, however, has so far been formally investigated. (M3 S1A) Hence, this study explores how indirectness finds its way in politicians' responses and the role obliqueness plays in face-saving and maintaining polite behavior. Furthermore, an attempt to decipher what really lies between yes and no was made by analyzing Filipino senators' answers to polar or yes/no questions.

With the results yielded in the study, it can be inferred that since MA and PhD students have more similarities than differences in the employment and non-employment of moves and sub-moves in the Introduction section, perhaps the writers have the same orientation as regards research paper writing. For instance, Move 1 (Steps 1, 2, 3) and Move 3 (Step 1A) have the most number of occurrences at 18, 19, and 15, respectively and 14 occurrences for Step 1A of Move 3 and no employment at all of Steps 1C and 1D of Move 2 and Step 2 of Move 3. For this set of writers, it appears that Move 1 Steps 1, 2, 3 and Move 3 Step 1A are obligatory moves/sub-moves while the rest appear to be optional or unnecessary since they were employed in less than 50% of the corpus. It is, however, too early to claim that these features are exclusive only to those enrolled in the English Language program because of the small corpus.

It can be noted that while Move 1 stands out as the favorite among all the moves with the presence of almost all of its sub-moves, it appears that the similarities and differences may be attributed simply to the writers' choice or preference for some sub-moves perhaps due to their orientation as regards the usage of the said moves with the indicator “and/or” for each sub-move. What is particularly striking is the absence of the sub-moves in Move 2 – Question-raising and Continuing a tradition and a choice between Counter-claiming and Indicating a gap. The indicator or coming after each step or sub-move gives the writer the liberty not to employ all the sub-moves. What is alarming though is the use of the sub-move Indicating a gap which was employed by only 10 of the 21 papers analyzed. The importance of such step may not be clear to the writers which confines them only to reviewing previous research but not indicating a gap found in the research reviewed, thus making the paper less accurate and scholarly. A reorientation as to the impact of such move should probably be underscored in academic writing classes so that graduate student-writers become accustomed to this writing practice which will pave the way for a more correct presentation of the study.

Finally, t-test was employed to determine if there is a significant difference between the average introduction moves employed by MA and PhD students. The t-test result showed that at 5% level of significance, there is no significant difference between these two introduction moves since the p-value was greater than 0.05 (p-value = 0.478& 0.955 for one- & two-tailed tests respectively).

Like the introduction, some novice researchers also find some difficulty in closing the research articles they write. While some follow the IMRD pattern (Introduction-Method- Result-Discussion), some also use the IMRDC pattern (with C as an added section which stands for Conclusion).

Table 2 shows the move sequences in the Conclusion section present in the papers analyzed.

Table 2. Move Sequences in the Conclusion Section of Academic Papers Written by MA/PhD Students

Using Yang and Allison's framework, findings revealed that all 21 papers employed the summary move (Move 1) in contrast to Move 2 (Evaluating the Study) which was used by only five MA students and seven PhD students. Unlike the moves and sub-moves in the Introduction section which give the writers options in employing the sub-moves/steps, Yang and Allison's framework do not give such choice to research article writers. Thus, all moves and sub-moves are required in writing the Conclusion section.

However, it is to be noted that only two MA papers and only two PhD papers employed two of the three sub-moves in Move 2: Indicating the significance of the study and Indicating limitations of the study. Evaluating methodology which comes as the last sub-move was not at all utilized. With regard to Move 3 (Deductions from the research), all papers except for one PhD paper employed Move 3. However, while Yang and Allison recommend the use of the sub-moves Recommendation and Pedagogical Implications, only two MA and two PhD papers employed both sub-moves. The rest of the papers made a choice as to the employment of any of the sub-moves earlier cited. The following are sample texts taken from the MA and PhD manuscripts.

This present research reveals that the reading program has a significant effect on students' vocabulary learning. It also provides evidence of the advantages and effectiveness of the reading program. (M2) As evident in similar studies, the study revealed that independent reading provides relaxation for students. They do not worry about being given an assessment or test after the DEAR activity, thus helping them acquire new words without pressure. However, the study also suggests that there is the need to have a followup investigation to determine whether a stricter implementation of the post activity leads to a decline in the student's interest in reading or doing the silent reading. Assessing the students' vocabulary performance through the DEAR program, it may be noted that learners develop a deeper understanding and appreciation for independent reading. (M3) Overall, it can be noted that the program is successful although it could still be recommended that teachers should continually explain to the students the importance of vocabulary building as well as encourage their students to regularly read interesting and relevant materials in class.

To come to the key point, the meaning of a response that cannot be easily classified as a transparent 'yes' or 'no' depends on the listeners' construal of utterances. What hides between yes and no therefore is what the listeners have in mind based on their pragmatic and semantic interpretations of the answers to polar questions. To be 'hearer-responsible' is a politician's evasive device, which if effectively used, would result in face-saving and politeness maintenance.

Politicians, in their constant quest to maintain rapport and to save themselves from political or even personal attacks, choose to be oblique and uncooperative in conversations especially when the polar questions are tough and risky. (M2) The data presented, although limited to ten transcripts, show that indirectness or lack of candor has instrumental purposes to serve and could work to the advantage of the politician interlocutors.

It would be necessary, however, to involve a larger corpus to further examine the other evasion tactics that surfaced in the present study. The researcher only took the liberty of naming them hence, more comprehensive investigations may be done to disprove or substantiate his findings. Further investigations might also want to concentrate on a longer stretch of discourse that delves into a specific issue since it is also necessary to discern what circumstances prompted a speaker to evade the polar questions raised. Political analysts and discourse analysts may work collaboratively in understanding a politicians' manner of handling polar questions so that more communication theories may be developed which would eventually shed light on the intricacies of political discourses.

To summarize the results in the Conclusion section, there are three moves/sub-moves which were found to be employed by the majority of the writers as seen in Move 1 (Summarizing the Study) and Move 3 (Recommends further research) with 21 and 14 occurrences, respectively thus making them obligatory. Move 2 (Evaluating the Study) was not employed at all by any of the writers. The other submoves all had 10 occurrences or below 50% making them optional moves. It cannot be said, however, that this feature is specific only to those enrolled in the English program since the corpus needs to be enriched.

Finally, t-test was employed to determine if there is a significant difference between the average conclusion moves employed by MA and PhD students. The t-test result showed that at 5% level of significance, there is no significant difference between these two conclusion moves since the p-value was greater than 0.05 (p-value = 0.493 & 0.985 for one- & two-tailed test respectively).

In the past, the use of the first person pronoun was not a practice in academic writing. In fact, academic writing teachers would emphasize the non-usage of the pronoun I to establish objectivity. Detachment as a feature is likewise to be observed and this can be achieved by the use of the term “the researcher” or “the writer” in many instances.

Recently, a new practice was introduced and that is the use of the I pronoun to establish authorial presence. Samraj's (2008), in her study noted that linguistics students' use of the Ipronoun appear to be largely metadiscoursal as compared to biology students who reflect the use of such feature as an agent in the writing process. Samraj then posits that to a certain degree, graduate student writers may have been oriented to the epistemological practices of their respective disciplines. Table 3 below presents the use of the “I” pronoun in the corpus.

Table 3. Occurrence of the I pronoun in graduate students' academic papers

The table clearly reveals that graduate students do not exhibit at all authorial presence in their writing outputs. Out of the 10 MA students, only two employed the I pronoun and to a very limited extent. In fact, for the two who employed such pronoun, there was only one occurrence for each. In the analysis, I included the my pronoun simply to establish reference to the writer concerned. It is to be noted that for this possessive pronoun, there were four occurrences of the my pronoun for Paper 6 and two occurrences for Paper 10. Other than the two, no other paper employed the I and my pronouns.

The following are some examples found in the corpus

#6 (Conclusion: Move 2)

The author discuss in the last part of the paper that the implications of the study to language teaching.

In this paper, she will present evidence on the composition of the early vocabulary of five Filipino children between 2-3 years of age.

With respect to the Ph.D. papers, no writer employed the I pronoun at all. This finding is somewhat striking since doctoral students are expected to be more adapt in academic writing; more so, they are used to making their presence felt with the arguments they present and the stance they take. As mentioned earlier, it also lessens the objectivity of the writer, thereby making his/her claim subjective. Detachment then is essential and should be observed from the beginning to the end of the text with this kind of orientation. As to establishing the student as an agent in the research process, this is not accomplished with the use of I in the text analyzed but through the use of “the/this researcher/writer” noun phrase.

According to Samraj's (2008), the use of the first person pronoun may point to the following purposes: 1.) to show that the writer is aligning himself/herself with the argument presented in the paper; 2.) even when the writer is presenting an overview of the thesis, the writer establishes strong authorial presence in as much as the organization of the thesis is presented in terms of the parts of the main argument.

With the very low incidence of the first person pronoun in the corpus, it can be deduced that the writers were not mindful of the functions of the I pronoun as identified above nor they consider the use of this linguistic feature as metadiscoursal. Articles written by Filipino researchers in the graduate level have been given the orientation to use the third person pronoun, usually employing the phrase “the researcher” in structures like “The researcher found out…”, “The researcher then believes” instead of the structures “I found out that…” and “I believe that…” Perhaps, a reorientation as to the acceptability of such feature should be underscored in academic writing classes so that graduate student-writers become accustomed to this writing practice which will lead to a stronger authorial presence and knowledge claim. This finding somehow supports Samraj's (2008)study which claimed that linguistics students took a more central position in terms of this scope. It is interesting to note that not one of the 11 Filipino PhD students employed the I pronoun in this study.

Noting the move structure of the introduction and conclusion sections of academic papers is significant to serve as guide to writers in giving direction to their writing outputs. However, strictly imposing on the employment of all the sub-moves may hinder the writer from exercising flexibility and the reasons for exercising such flexibility. As earlier cited, there are some moves most favorable to the writers and some which have been completely disregarded. This study is then important to know why students enrolled in the English program find favorable some sub-moves and unfavorable some other sub-moves. The study, though, is limited to only 21 research papers and while findings may not be conclusive, it also raises consciousness among student-writers in English that there is a wide range of possibilities that could probably influence them why they adopt and not adopt certain moves or submoves. Moreover, the sample though small, has been subjected to a critical analysis of three coders where a discussion of the most essential detail has been attended to

In spite of the coding of all 21 papers made by the three coders, it is still recommended that the sample be increased to make the findings more conclusive. Moreover, an analysis which will focus on the organizational moves in the Discussion section will render the study more detailed and complete. An assessment of the obligatory and optional moves is likewise endorsed for all sections.