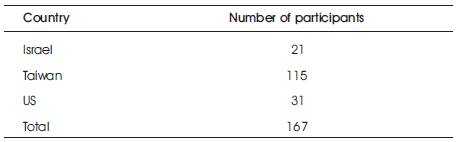

Table 1. Number of Participants by Country

This study examines the use of formulaic language in an intercultural communication encounter. It focuses particularly on phatic expressions used in an online discussion about gender stereotypes in English among 167 undergraduate university students in Taiwan, Israel, and the US. Content analysis methodology was used to examine whether there are differences in the openings and closings that the students from the different countries used in their self-introductions. The analysis also sought to discover whether the participants regard online discussion as writing or speaking by analyzing the types and frequency of expressions used. While the results did offer strong support for there being cultural differences in the usage of phatics, the analysis of these formulaic responses does point to the use of an informal style of writing rather than the interactions imitating oral communication. Therefore, rather than being a form of speaking or writing, or a combination of the two, perhaps online writing is evolving into a specific form of communication with its own conventions for using phatics to establish and maintain connections in the online environment.

This article reports on a study which examines the use of formulaic language in an intercultural communication encounter. It focuses particularly on phatic expressions used in an online discussion in English among university students in Taiwan, Israel, and the US. The purpose of the study was to examine whether there are differences in the openings and closings that the students from the different countries used in their self-introductions.

Phatic expressions are a type of formulaic verbal language or nonverbal communication which serves the purpose of starting and ending an interaction. Such routine greetings tend generally carry no essential information. While seemingly trivial, sociologists (Duranti, 2001) say that the purpose of such “small talk” is to open up social or interpersonal channels. They are used to set the stage through routine greetings or through nonverbal communication, such as a handshake. To sustain communication, there must be a balance between the amount of phatic communication and factual communication. If there is too much small talk, the communication is unfocused. However, if there is not enough, the interaction seems too formal or restrained.

These types of interpersonal communication are evident in face-to-face encounters. When people meet, they may shake hands, smile, and/or exchange a few phrases, such as “Hello. How are you?” As the encounter continues, they may nod and make utterances that help move the conversation along, such as, “You don't say.” When an exchange ends, there may again be handshakes, and formulaic parting phrases, such as “See you later.” All of these communication devices build connections among the interlocutors, and develop the depth and breadth of their interpersonal communication (Gass & Selinker, 2001; Richards & Rodgers, 2001).

Research (Belz, 2003; Chen & Wang, 2009; Cifuentes & Shih, 2001; Domingues Ferreira da Cruz, 2008; Liaw,2006; Solem, Bell, Fournier, Gillespie, Lewitsky, & Lockton, 2003; Warschauer, 1996; Zha, Kelly, Park, & Fitzgerald, 2006) has shown that even in an online environment, interpersonal communication is important for building connections among the participants. Phatic expressions are one way of building these connections.

The type and amount of phatic expressions is culturally determined (Duranti, 2001; (Gudykunst & Kim, 2003). In the American culture, the phrase “How are you?” is often used as an opening phrase. Even if one is feeling terrible, the expected formulaic answer is, generally, “I'm fine.” In other cultures, the asker of this question may expect a detailed answer about one's health or well-being. Therefore, when members of different cultures are communicating there is the possibility of miscommunication and misunderstanding based on the implementation of different sets of rules being employed in how and when these expressions are used. There is the added complication of participants communicating in a common language which may not be the L1 of all participants. Based on their cultural perspective, they may have learned different meanings and uses of some of these phrases (Gudykunst & Kim, 2003).

In the online environment, these issues are equally present. Even though participants are writing to one another, an online discussion contains the initial period where participants have to introduce themselves to one another. This article focuses on these particular interactions.

The data for this study, taken from an online discussion about gender stereotypes among undergraduate university students in the US, Israel and Taiwan were analyzed using content analysis methodology. The data set that was isolated for analysis were the students' self-introductions.

Content analysis is a research method which examines texts for the presence of and/or frequency of certain words and phrases. “Researchers quantify and analyze the presence, meanings and relationships of such words and concepts, then make inferences about the messages within the texts, the writer(s), the audience, and even the culture and time of which these are a part” (CSU, 2011a, para. 1). One use of content analysis is to “reveal international differences in communication content” (CSU, 2011b, para. 1). The research design, based on conceptual analysis of the text(s) begins with identifying research questions, then selecting words and phrases to be coded into content categories that address the research question(s) (CSU, 2011c). Texts are then coded using these categories and analyzed accordingly.

This study was based on the hypothesis that there will be some difference in the openings and closings that the students from the different countries used, and that these differences will be in the amount of formality of the utterances and the structures used. The content analysis of the introductions attempts to answer two research questions:

(i). How will the use of phatics differ among participants in each country?

(ii). Can phatic expressions give an indication of whether the participants regard online discussion as writing or speaking?

To test this hypothesis and to answer the research questions, the utterances were compared to this formulaic exchange which is closely based on an American cultural norm for introductions:

Introduction: Hello. My name is… I am… (Personal information) I am looking forward to…signature

Response to others: Hello, XXX. It's nice to meet you. (Ask a few informational questions)…signature

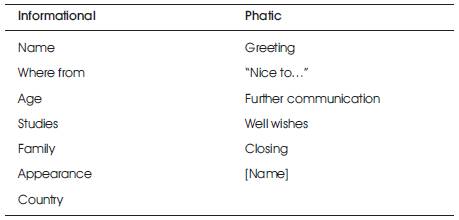

To analyze the data for both research questions, two broad categories were created: openings and closings. These two categories were further subdivided into: informational and phatic. Phatic expressions were further categorized as: formal and informal greetings, by name, desire for continuation, and “polite” phatics. Frequencies for each of these categories and subcategories were calculated and analyzed for patterns.

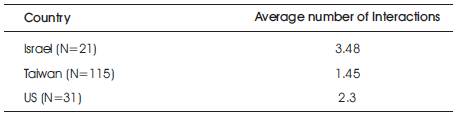

There were 21 participants from Israel; 31 participants from the US; and 115 from Taiwan (Table 1). All of the participants were undergraduate students. The Israeli students and Taiwanese students were enrolled in different levels of English as a Foreign Language courses. The students from the US were enrolled in a Diversity & Education course for pre-methods students. None of the Israeli or Taiwanese participants were native speakers of English. Most of the students from the US were native speakers of English and few who were not, were bilingual.

Table 1. Number of Participants by Country

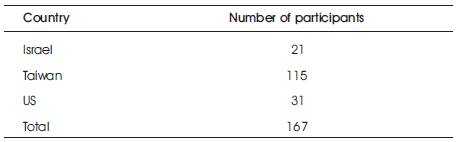

The first data point to consider is the number of openings and closings that were posted. Some of the participants interacted with more than one other participant. For the purposes of this research, an opening is any type of greeting and/or opening phrase that is formulaic. A closing is any type of formulaic ending phrase or the participant's name. The Israelis had 43 opening interactions, and 30 closings. The Taiwanese had 122 opening interactions and 46 closings. The students from the US had 52 opening interactions and 20 closings. All but one of the 217 interactions used some type of introductory greeting or other phatic expression. On the other hand, there were 96 closing expressions (Table 2).

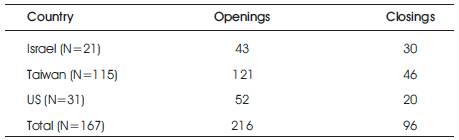

The next step was to create categories for these openings and closings. The introductions tended to have two kinds of utterances, informational and phatic. One was informational: name, where the person was from, their age, what they were studying, family information, what they looked like, and information about their country. The others were phatic, such as: greetings, “nice to meet you” type phrases, expressions of hope for further communication, well wishes, and closures. For the purposes of this project the informational category, “name” was also placed in phatic expressions (Table 3).

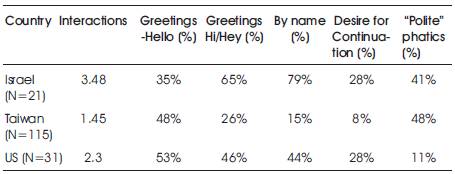

All of the participants were instructed to post their introduction and to respond to a person from each country. The Israeli participants seemed to be more active than the other participants. They had an average of 3.48 interactions per person. The participants from the US had an average of 2.3 while the participants from Taiwan had an average of 1.45 (Table 4).

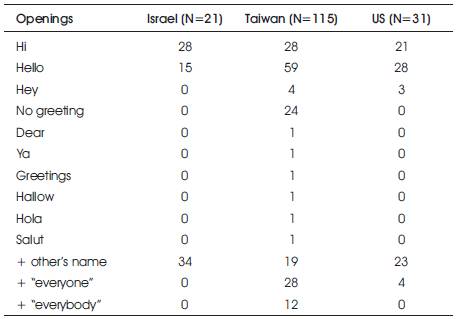

There were several patterns that emerged in the Openings, which were categorized as Greetings and Other. Of 43 opening interactions, the Israeli participants tended to make their introduction in response to other participants. Most of the Taiwanese respondents, on the other hand, posted only their introduction and replied to few other participants. Also, of the 115 Taiwanese participants, 24 of their Openings had no greeting. In general, all the participants used the less formal Hi or Hey and the slightly more formal Hello. These greetings are more typical of spoken language and informal writing. One Taiwanese student did use the greeting “dear” which is usually in formal letter writing ( Table 5).

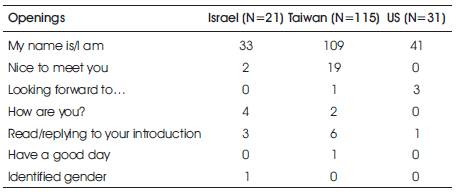

The other category of Openings was labeled other. These include My name is/I am. and some general phatic utterances, such as Nice to meet you and Looking forward to… ( Table 6).

Most of the participants identified themselves as part of their opening, whether they were introducing themselves or responding to others. It also appears that the participants from the US, the native speakers, used fewer of the standard phatic phrases associated with openings.

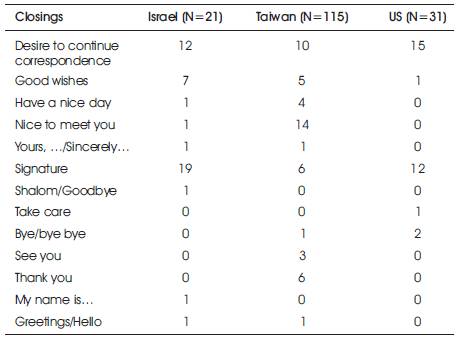

The Closings did not fall into strong patterns. Only 2 participants used a signature closing, such as sincerely, although a number of the Israeli and respondents from the US signed their names. Very few of the Taiwanese students signed their names. A number of them did express a desire in one or another for further correspondence. The only students who wrote Thank You were the Taiwanese participants (Table 7).

Table 2. Number of Openings and Closings by Country

Table 3. Informational and Phatic Categories of Openings and Closings

Table 4. Average Number of Interactions by Country

Table 5. Number of Openings – Greetings by Country

Table 6. Number of Openings – Other by Country

Table 7. Number of Closings by Country

The content was analyzed to try to determine if there was some difference in the openings and closings that the students from the different countries used, and if these differences were related to formality of the utterances and the structures used. Two research questions were formulated to test this hypothesis.

(i). How will the use of phatics differ among participants in each country?

(ii). Can phatic expressions give an indication of whether the participants regard online discussion as writing or speaking?

The data were compared to a formulaic exchange which is loosely based on an American cultural norm for introductions.

The content analysis of the introductions revealed that it is difficult to draw any particular cultural conclusions from these data. The differences that were found may have been culturally based; they may have been a result of how the students were taught to use these conventions or how they understand they are to use them; or they may have been a result of how the students viewed the activity.

The categories for this analysis were: formal and informal greetings, by name, desire for continuation, and “polite” phatics, those phrases which express “nice to meet you” and so on. The number of interactions and the various phatic devices were compared as follows (Table 8).

Table 8. Percentage of Phatic Devices Used by Country

First of all, only one Taiwanese student used the more formal “dear” which is formal letter writing convention. If we consider “hello” the more formal of the greetings used, then more Taiwanese used that slightly more formal greeting. Participants from the US used about an equal amount of the more formal “hello” and the informal “Hi/hey.” A larger percentage of Israeli participants used the more informal “Hi.” In addition, 24 of the Openings from Taiwanese students had no greeting.

All of the participants were instructed to post their introduction and to respond to a person from each country. The Israeli participants seemed to be more active than the other participants. They had an average of 3.48 interactions per person. Out of 43 opening interactions, the Israeli participants tended to make their introduction in response to other participants. They responded using an individual's name 79% of the time.

The participants from the US had an average of 2.3 interactions. They responded using another person's name 44% of the time. This percentage is consistent with the post/responses pattern of the assignment. Four participants addressed their general introduction to “everyone.’

The participants from Taiwan had an average of 1.45 interactions. Most of the Taiwanese respondents posted only their introduction and replied to few other participants. Of these introductions, 33% of the participants addressed their introduction to “everyone/everybody.” Only 15% responded by name, which is consistent with the low percentage of responses.

About ¼ of the Israeli posts and about ¼ of the posts from the US expressed a desire for continued communication. Only 8% of the Taiwanese posts used this phatic device.

The final category is “polite phatic expressions”. These expressions were used by 41% of the Israelis, while 48% of the Taiwanese used them. Only 11% of the students from the US used these types of expressions.

From these data, it appears that the Israelis treated the activity as a more informal type of communication than the other two groups. Judging by the phatic expressions they used, it appears the Israeli students were interested in interacting and communicating more freely than their counterparts in the other countries. The Taiwanese students seemed less interested in communicating with others than in merely posting their introductions as part of the assignment.

Looking at the “polite” phatics data, one may conclude that the participants from the US saw the activity as a more static writing activity than did the other two groups. They wanted to communicate, but did not view the activity as a personal or social activity.

The second research question referred to whether the participants regarded the online discussion as writing or speaking. The answer is a qualified “Yes.” From the analysis, it appears that the participants viewed this activity as an informal writing activity (Table 8).

First of all, it is apparent that the students did not see this in the same way as a formal writing exercise, an exercise in which they adhere strictly to formal writing conventions. However, their use of phatics shows that their introductions contain elements of written and oral communication conventions. For example, the greetings, which were mostly informal, were more consistent with spoken introductions than with formal written introductions.

An examination of the closings shows that the participants from Israel and the US, in particular, signed their names, even when they had said “My name is…” earlier in the interaction. A signature is definitely a written communication device. About half of these same participants also expressed a desire to continue the communication, which is more consistent with written than oral communication.

All of the participants also introduced themselves frequently. This may be more a function of at least one of their posts should have been their introduction. However, this type of repeated introducing of oneself is not an oral convention. It serves more of a purpose when the communication is among people who cannot see one another and are communicating asynchronously.

However, fewer than 50% of the participants used “polite phatic expressions,” those which express “nice to meet you” and so on. The one conclusion that may be drawn is that the participants did not view these interactions in the same way that one views an oral interaction in which one says the formulaic – Hello – how are you – nice to meet you, etc.

These data seem to support the conclusion that while there are elements of oral communication demonstrated by the greetings, overall the activity was approached as a writing activity. However, it was not approached as a formal writing activity with a thesis statement, supporting evidence, etc. The participants approached it more informally, more like an informal letter writing exercise.

This study has several limitations which may have affected the data analysis. The limitations were related to background information about the assignment and the students' writing proficiency; lack of information about the use of phatics in the participants' L1; and sample size.

First of all, this study does not provide background information about the specific instructions that the participants were given when engaging in the online discussion. The study did not include the specific instructions that students in each country received. The specific assignment instructions may have impacted how they responded, such as how they were supposed to compose their introductions or the number of times they were supposed to interact.

Secondly, the study instruments did not collect any information about the students' previous writing experiences. Their competency in writing English could have impacted their ability to post and respond consistently with other participants.

In addition, there is no information about writing and speaking conventions and the use of phatics in their L1s. Such information could be used to pinpoint what may have caused differences in the usage of phatics in these introductions.

Another limitation is that this study used a small section of data from a larger project, focusing only on the participants' uses of phatics in their introductions. A further analysis of phatic usage in all the interactions may have yielded more or less support for some of the conclusions drawn here.

Despite its limitations, this study offers some insight into the use of phatics in online discussions. Phatic expressions are a way of establishing connection. They also lend a degree of predictability to the communication. Writing is different from speech in that it has less immediacy. It allows communication between people at a spatio-temporal distance, which has implications for an online discussion because (i) people can think about and plan what they are going to “say” and (ii) phatic expressions must be used to create the connection because of the lack of nonverbal cues, such as facial expressions, body language, etc.

However, online communication has a different sense of distance than conventional forms of writing. It can feel more immediate because 1(i) it is more public - all participants can see what you wrote and respond to it, and (ii) there is the possibility that the interactions can take place in almost real-time. Therefore, online discussion can take on some of the qualities of oral communication.

The analysis of these formulaic responses indicates the use of an informal style of writing rather than actually imitating oral communication. Therefore, rather than being one or the other, speaking or writing, or a combination of the two, perhaps online writing is evolving into a specific form of communication with its own conventions for using phatics to establish and maintain connections in the online environment.