Table 1. Profile of the Teacher Respondents (N=50)

Because it has been established that there is a local variety of English born in the Philippines, there are crucial debates specifically on what pedagogical standard must be used in teaching English in Philippine schools. In spite of the growing number of researches on Philippine English (PE) and the publication of its own dictionary, it appears that a considerable number of educators, language learners, non-educators, and professionals still deem that the so-called 'Standard English' variety also known as 'ENL' (English as a Native Language) (Kirkpatrick, 2007), and 'inner circle' variety (Erling, 2005) is “innately superior to ESL and EFL varieties and that it therefore, represents a good model for English for people in ESL and EFL contexts to follow” (Kirkpatrick, 2007, p. 28). This study therefore explores the prevailing perceptions of college students and language instructors in the oldest university in the Philippines and in Asia toward the two main varieties of English that thrive in the country – American English (AE) and Philippine English (PE) as well as their motives for learning and teaching the English language. This study shows that a majority of the student and teacher respondents have similar reasons why English is taught and studied in the Philippines and that between AE and PE, AE remains as “the” privileged English variety. This paper also examines more specific contentious issues on (i) the language learners' motives for learning English (ii) reasons why Filipino language teachers and learners privilege AE; and (iii) the Filipino learners and teachers' prevailing unreceptive attitudes towards PE. This paper then explicates some of the contributing factors that influence the respondents' choice of variety and proposes 'de-hegemonizing' agents that may result not only in the popularization of Philippine English but also in the gradual liberation of the Filipino language teachers and learners from the shackles of the colonizing power of AE.

English language teaching and learning in the Philippines has constantly faced a myriad of contentious issues. There have been reports on the widespread erosion of Filipinos' proficiency in English and that their speaking, listening, reading, and writing skills in English are on a continuous and an unabated decline. The blame has been put not only on the language teachers but also on other factors like media, popular culture, and technology. Issues in relation to the prescribed medium of instruction in the classrooms have not been resolved as well. There have also been debates as to whether the Philippine educational system should revert to the use of Filipino, the national language, in teaching the different content areas or should promote multilingual and mother tongue-based education. The issues on multiculturalism in the classroom, how technology adversely or favorably affects language instruction, and the colonizing power of English are also a part of the seemingly problematic picture. These and more are the perplexing issues that beset the realm of language instruction in the Philippines.

The aforesaid issues emanate from the use of English as the primary medium of instruction in the Philippines and as the language of intranational and international communication. As Kachru (1997) puts it “…the prolonged presence of the English language has raised a string of questions that have been discussed in literature, not only in English but also in other major languages…” (p.2). In the Philippines, for instance, the English language has enjoyed a privileged status in formal education for decades and its domination has been challenged since then (Bernardo, 2004). Quite undeniably, despite all the mounting questions and oppositions, English still remains as a favored language in the country. Different sectors, principally the national government, still push for the constant learning of English notwithstanding the growing objections against it.

Time itself has become a witness to the growth and diffusion of English across the globe. The adoption of English by many Asian countries like the Philippines, not only as an aftermath of years of colonization but also of personal and communal will, has probably led to its elevation to the pinnacle of language hierarchy. Further, favoring this foreign language seems to perpetuate its hegemonic power over other languages in communication and causes what Tsuda (2008) calls the 'English Divide' or “…the inequalities between the English speaking and non-English speaking people” (p.47). The English language itself and its different faces which Kachru (1986) and other language gurus call 'varieties', appears to have created a perceptible demarcation line between 'the' standard and other varieties born via nonnative speakers' colonization, nativization, and owning of the language. The same demarcation line, however, is deemed to have caused nonnative speakers to favor one variety over the other.

In the Philippines, English was introduced when the American colonizers set foot on its archipelagic shores more than a hundred years ago. After the Philippine-American War, Filipino teachers were trained under the tutelage of the American educators known as Thomasites, and this flock of Filipino teachers was diffused in various places and was commissioned to teach English to Filipino learners (Gonzalez, 1997). English was formally introduced to the educational system when US President William McKinley issued a pronouncement on April 7, 1900, declaring that English be used as a medium of instruction across different levels (Bernardo, 2008). Hence, a good number of Filipinos spoke, wrote, read, and listened in English. Prose and non-prose publications started to use the colonizers' language and since then, “English - the means the Americans used to teach [Filipinos] via the mass media, the arts, social, business and political interaction - continues to be a strong thread that binds the two nations” (Espinosa, 1997, p.1).

What is more interesting than the historical memoirs of English in the country is the fact that in the Philippines, the native-born speakers' constant use of the transplanted language has given birth to a local variety. This birth, however, is also a reality in many countries beyond the walls of its archipelagic landscape. Hence, it is not surprising to hear the names 'New Englishes' (Platt, Weber & Ho, 1984) or 'varieties of English' or 'the English of the Outer Circle' (Kachru, 1986; 1992) used to baptize the local varieties that evolve from nonnative speakers' use of English. Njoroge and Nyamasyo (2007) opine that now, “Users of English speak and write English differently and as an imported language in many countries, it has inevitably undergone local changes that have evolved into distinct and different varieties of a language” (p. 60). Kachru (2006) also figuratively words that “It is now generally recognized that the Hydra-like language has many heads, representing diverse cultures and linguistic identities” (p. 446). Kachru (1986) graphically represents this Hydra-like language through the Three Concentric Circles of English: The Inner, Outer, and Expanding Circles. The Inner Cirlce represents the countries where English is used as a first or native language (L1) e.g. USA, UK, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. The Outer Cirle symbolizes countries where English has been institutionalized as an additional language and as a second language (ESL) e.g. Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, India, and Kenya. The Expanding Circle refers to countries where English is regarded as a foreign language (EFL) e.g. China, Korea, Japan, Brazil, and Norway. Consequently, the pluralized term 'World Englishes' has become extremely popular and a plethora of studies about local varieties e.g. Nigerian English (Bamgbose, 1982; Banjo, 1995), Singaporean English ( Platt, Weber & Ho, 1984), Indian English (Coelho, 1997; Kachru, 1983), Malaysian English (Omar, 2004), Japanese English (Ohashi, 2005; Matsuda, 2002; Matsuura, Chiba & Yamamoto, 1994), and Philippine English (Bautista & Bolton, 2008) have been conducted in the Asian sphere and its periphery over the past years. Kachru's seminal work has undoubtedly spurred the interest of linguists and EFL (English as a Foreign Language) and ESL (English as a Second Language) practitioners and until now, debates and further investigations on the ownership, localization, and nativization of English and acceptability and comprehensibility of local varieties are undertaken in the different corners of the world.

In the Philippines, for instance, Bautista (2000) found that studies on the status, structure, features, intelligibility, and acceptability of Philippine English (PE henceforth) have accumulated over the past decades; the very first was written by Llamson (1969) which did become the trailblazer for other local researches. In the succeeding years, more researches on PE were conducted. In Bautista's comprehensive review, she condenses the studies of Martinez (1972), Alberca (1978), Sta. Ana (1983), Gonzalez (1984), Casambre (1986), Dar (1973), Aranas (1988), Romero (1988), Jambalos (1989), Gonzalez (1985), Sanchez (1993), Aquino et al., (1966), Tucker (1968), Luzares & Bautista (1972), Fallorina (1985), Aglaua & Aliponga (1999), Lagazon (1975), Buzar (1978), Sarile (1986), Ponio (1974), Park (1983) and Gonzales (1990). Since Bautista's interests include PE, she also completed and published an overwhelming number of papers on the local variety of English. These include: The lexicon of Philippine English (1997); Defining Standard Philippine English: Its status and grammatical features (2000); The grammatical features of educated Philippine English (2000); Studies of Philippine English: Implications for English language teaching in the Philippines (2001); The verb in Philippine English: A preliminary analysis of modal would (2004); ICE-Philippines Lexical Corpus - CD-ROM (2004); and Investigating the grammatical features of Philippine English (2009). Since PE research is still a fertile ground for investigation, more were published just recently e.g. Dayag (2004), Madrunio (2004), David & Dumanig (2008), Borlongan (2008), Tayao (2008), Bolton & Butler (2008), Lockwood, Forey & Price (2008). It is imperative to enumerate all these studies for they attest that in the Philippines, a nativized variety of English characterized by its own distinct lexicon, accent, and variations in grammar has emerged and has thrived since English was initially diffused in the different parts of the country and used in various domains e.g. politics, education, economics, and trade. These past investigations would clearly show that the presence of a localized variety of English in the Philippines is a glaring and an incontestable reality.

It must be (re)emphasized, however, that the variety named PE in the aforesaid and present studies is the 'educated' Philippine English i.e. the English “produced by competent users of the language in formal situations” (Bautista, 2000, p. 156), and the “variety propagated by the mass media, which includes not only the idiolects of its broadcasters and anchormen but likewise the idiolects of the elites and influentials of Philippine society…” (Gonzalez, 1983, p. 111). It may be deduced therefore that PE is a unique 'brand' of English used by the vast majority of educated Filipinos and apparent in various forms of mass media – print or non-print, literary or non-literary.

This study therefore aims to uncover what English users in the oldest university in the Philippines and in Asia prefer as 'the' variety to be taught in all learning institutions and eventually use for different purposes. This paper carefully examines more specific critical issues on (i) the language learners' motives for learning English, (ii) the reasons why language teachers and learners favor American English (AE), and (iii) the learners and teachers' prevailing unwelcoming attitudes towards PE. This paper considers the aforementioned as contentious issues to ponder on, explains why such issues need to be promptly addressed and theorizes on what alternatives or paradigms may be adopted with the end view of making English not as a divisor or an enslaving entity but as a language that has a noble purpose to serve.

This study employed the survey method of research. A researcher-made questionnaire was used as the primary data gathering tool. The questionnaire was pre-tested to three English teachers and five college students to ensure the clarity of instructions, questions, and responses. In the case of the student respondents, some of the items in the questionnaire were modified and simplified to facilitate better comprehension. The questionnaires were fielded online and personally after seeking permission from the concerned school officials.

Three sets of respondents from the University of Santo Tomas (UST) were involved in this investigation: 50 English teachers; 167 randomly selected college students from the College of Education, College of Tourism and Hospitality Management, and Faculty of Arts and Letters, 134 conveniently sampled freshmen students of the researcher during the first semester of Academic Year 2009-2010. Their majors include Asian studies, economics, communication arts, and behavioral science.

University of Santo Tomas (UST), the oldest university in the Philippines and in Asia, was selected as the study site because the proponent is a member of the faculty of the UST Department of English. Also, the UST Department of English is on its initial stage of reformulating a language policy and redesigning a language plan for the whole institution composed of several colleges and institutes. Hence, UST English teachers and college students were involved in this investigation since findings of this study would also redound to their own advantage and since they are representative members of the university population.

The 167 student respondents together with the 50 English teachers were asked to fill out a parallel questionnaire asking for their demographic profile, three main reasons for teaching and learning English, and preferred variety of English.

The other 134 student respondents had formal lessons on the notion of PE. These students were enrolled in the researcher's English class. An instructional plan outlining the three-day classroom tasks and issues that center on PE existence was developed and executed by the researcher himself. After the discussion of the lesson which includes what PE is, who speaks PE, phonological, lexical, and syntactic features of PE, issues on acceptability and intelligibility and future of PE, they were individually asked to answer the open-ended question “Which variety of English should be taught in all Philippine schools and why?” The intention was to discover if the students' familiarity with or knowledge of PE as a result of the explicit classroom-based teaching of PE will make them opt for the 'nativized' variety. The researcher deemed this necessary since exposure to PE might make these students realize that there exists a local variety of 'educated English'. The researcher simply wanted to investigate if there would be changes in the choices of English variety of the 134 students after they have been formally introduced to PE and to the issues that relate to it.

The students' responses were tallied and synthesized as shown in the next section. Frequencies and percentages were the only numerical values computed for purposes of data presentation and analysis.

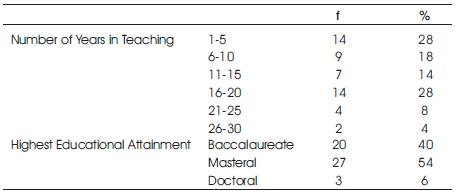

Table 1 presents the profile of the teacher respondents. It could be gleaned that the present study did not purposively choose only those who are seasoned in the field of language teaching and educators who have earned higher educational degrees. The data also show that a large percentage (28%) of the respondents has been in the profession for 1-5 and 16-20 years and that a majority (54%) have earned their graduate degrees.

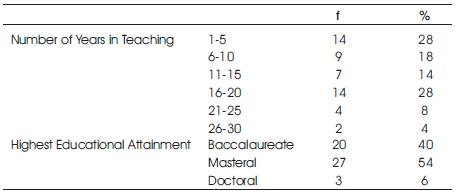

Table 2 presents the profile of the 167 student respondents. The figures show that a good number (69.46%) have been formally studying the English language for 11-15 years. Only 16.67% have studied English for 16-20 years. Some of them have already earned diploma courses and still intend to finish another baccalaureate degree. It is puzzling to note, however, that there are respondents, 4.79% and 8.98%, who have studied English for only 1-5 years and 6-10 years respectively. A probable explanation is the respondents' miscalculation or misunderstanding of the item since it is quite impossible for them to have studied English for only less than ten years when in fact, in the Philippines, elementary and secondary education are finished in approximately ten years. Within this timeline, English is not only used as a medium of instruction but is also offered as a separate discipline. Perhaps, these respondents inadvertently excluded the years they spent for studying basic and high school English subjects. The table also shows the breakdown of the respondents according to courses or majors. It must be made clear, however, that the other courses in the study locale were not involved in the investigation.

Table 1. Profile of the Teacher Respondents (N=50)

Table 2. Profile of the Student Respondents (N=167)

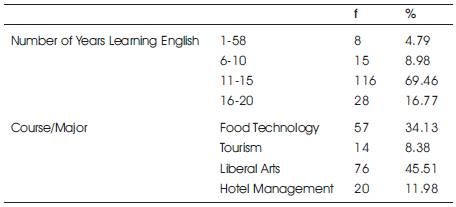

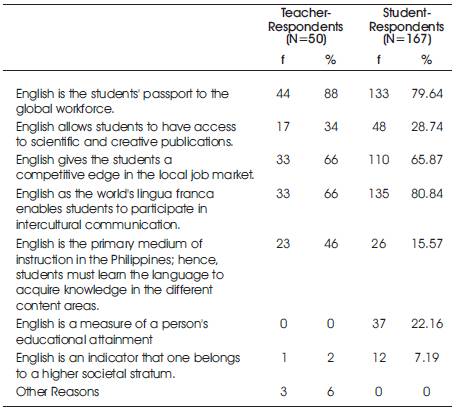

Table 3 gives the most paramount reasons why the English language is learned according to the teachers and students surveyed. The data clearly show that when ranked according to the respondents' preference, the three most important motives for learning English are (i) English as the world's lingua franca enables students to participate in intercultural communication, (ii) English is the students' passport to the global workforce; and (iii) English gives the students a competitive edge in the local job market.

Table 3. Teachers and Students' Reasons for Teaching and Learning English

Apart from the options provided, three respondents forwarded additional reasons why they consider learning English significant. Culled verbatim, these include:

The data suggest that learning English appears inevitable. The aforementioned results seem to affirm Murcia's (2003) claim that everyone strives to learn English not only because of its opulence of literature but also of its pragmatic aid in search for better opportunities. She further emphasized that English is learned for social mobility and its worth in professional milieu. The results are also reflective of Scrase's (2004) view that “it [English] served to maintain an externally imposed hegemony while facilitating the perpetuation of a caste and class-based domination by the indigenous elite” (p.2) and Bourdieu's (1991) assertion that English has become a valued linguistic currency and a form of cultural capital. The data also suggest that the ability to use English has probably caused language teachers and students to look far beyond the Philippine shores with the principal motivation of engaging in borderless communication and participating in the global market. This, however, calls for revisiting the present language curricula and critical introspection on the part of the teachers and students to discern whether to ensure the quality of human exports, to equip the language learners with requisite workforce skills and to allow the students to cross the borders in forging links with other cultures, are the very objectives of language teaching and learning.

An analysis of the 2002 Basic Education Curriculum for English would show that there is no explicit provision for the first two perceived goals of language teaching cited above. It is only that English be used as a medium for learning and appreciating other cultures which Smith (1983, as cited in Matsuda, 2003) questions by stating that communicating with other cultures does not reflect the reality of English language at present. Tupas (1999) in his essay Coping up with English Today argues that Filipinos want English because of 'instrumental reasons'. He further argues that Filipinos grapple to learn English because they think this language will open doors for them; it will make them financially prosperous and will enable them to see the world. This, however, could serve as an impetus for the Philippine educational system to discern if the intentions of the present curricula are what the Filipino learners desire. On the other hand, if they feel that this should be offset because there are other central reasons for learning English, a further revision of the language curricula may be necessary.

The clamor for learning English as an economic investment is probably rooted on the desire of the Philippine government and other social units like the students' own families to produce more proficient overseas Filipino workers. Magno (2004) believes that the English language is a 'legacy of colonial occupation' and a 'valuable national asset'. Thus, it is not surprising to see local newspaper articles frequently headlining the Philippine government bragging about Filipino workers who are easily hired and promoted when they apply for jobs abroad just because they speak 'good' English. This, however, seems debatable since no data has proven that Filipino job seekers were immediately employed or promoted by foreign companies like those in the United States or Canada because they know English and not because of their passion for work and their work ethics. Monsod (2003) reiterates that despite the fact that Filipino workers possess technical and relational skills, their waterloo remains to be their English language incompetence.

The data further imply that Filipino students and teachers perceive language learning as a means to reach the so-called 'American Dream' and be a part of what Murcia (2003) calls 'imagined paradise' because of the preconditioning they receive from their immediate environment. Perhaps, the expectations of outside forces subtly pressurize both students and teachers to aim for the global labor force. Teachers and students both submit themselves to the prevailing perception that working abroad is the key to a better life and that the key to a better life is to have the facility of the English language.

The data in Table 3 also show that since English is used as the foremost language of instruction in Philippine schools, students must aim to be proficient in the English language to acquire knowledge in the various content areas like science and mathematics and that they need English to have access to publications and instructional materials printed in English. Although this ranks comparatively low among the choices, this yet implies that unless the educational system accepts the idea that learning can best take place when native languages are used as media of instruction (Yanagihara, 2007; Walter, 2008), and using the language the learners understand, not only enables them to immediately master curricular content, but in the process, affirms the value of their cultural and language heritage, English teachers would insist that their students read, speak, and write purely in English. While it is good to note that teaching the content areas using the students' native languages has caught the attention of some concerned local groups, it has not gained national appreciation for many reasons e.g. law enforcers themselves promote English as the sole medium of instruction in the country.

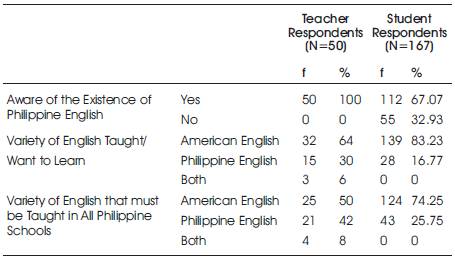

Table 4 presents the language teachers and students' preferred variety of English. It can be gleaned that even if all teachers are aware of the existence of Philippine English (PE), 64% adhere to American English (AE) as their pedagogical model and only 30% use PE as their instructional norm. The three teachers who disclosed that they teach both varieties specified that in grammar instruction, they rely on the so-called exonormative model (AE) but in teaching phonology, they acquiesce to the sound system of PE. The data also show that the teacher respondents are divided when asked about the English variety that must be imposed in all Philippine schools.

Table 4. Teachers and Students' Awareness of Philippine English and Preferred Variety of English

The same table shows that only 32.93% of the student-respondents are cognizant of the existence of PE and an overwhelming 83.23% want to learn AE. Further, three-fourths of the student respondents push for AE as the variety to be taught in country.

Matsuda (2003) argues that a disinterest in the native varieties is caused by the lack of responsiveness and the same disinterest in return, also reinforces the respondents' lack of awareness. Hence, there is a need for both language learners and teachers to be further exposed to competing paradigms, not only to make them cognizant of the different varieties of English but also to lead them in making informed choices.

Further analysis of the data would show that the instructors who have been in the teaching profession for more than 15 years prefer the exonormative or native speaker model. The result supports Tupas' (2006) argument that “[w]hile teachers seem critically aware of the competing paradigms of teaching English, their choices are also constrained by socio-economic, political, and ideological conditions which are largely not of their own making” (p.170). In the case of Filipino language teachers, they might be constrained by the factors Kirkpatrick (2007) identified as (i) legitimacy and prestige of the native speakers' model; (ii) availability of teaching materials based on the exonormative model; and (iii) imposition of the government that students be exposed to internationally recognized and internationally intelligible variety of English. Tupas (2006) further emphasized that teachers regard PE as legitimate but they rather not overtly or deliberately teach it. He argued that the fusion of the pragmatic force of Standard English (SE) ideology and the promotion of the global market because of great labor demand greatly conditions teachers to privilege the ruling standard. This practice , Mazzon (2000) exclaimed, has its colonial roots that only native speakers' English is acceptable and local varieties are inferior.

Despite this prevailing viewpoint, the data signify that there are language teachers who now overtly promote the use of the local variety. Most of them are relatively young (from 1-10 years) in the teaching field. This shows that there is a positive change in the teachers' perspectives. There are teachers who now gradually disregard American English which Matsuda (2003) calls the 'prototype of English speakers'. It seems that the birth of World Englishes has made the teachers more receptive to newer paradigms making them more critical and responsive to the demands of the present-day language instruction. Hence, language teachers must continue to engage in professional upgrading to keep themselves abreast with the latest trends, philosophies, and issues that ensue from the teaching of English. Those who have been made aware of the nativization of English may also be prompted to create ripples that would trigger more profound consciousness and understanding of the issues purported herein.

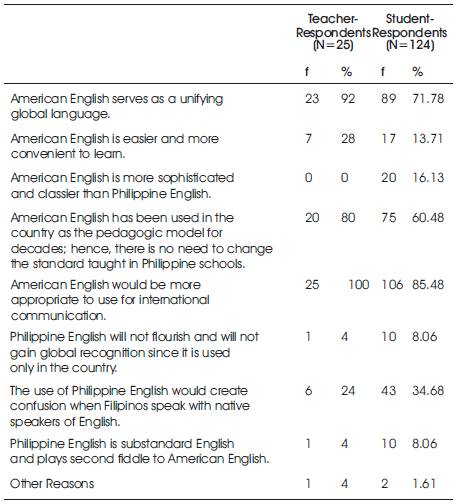

Table 5 presents the different reasons why 25 of the teacher-respondents and 124 out of the 167 student informants favor American English as the pedagogical standard in the Philippines. The results clearly show that a majority consider American English as (I) the appropriate variety to use for international communication; (ii) the unifying language of the world; and (iii) the model to be used permanently since it has stood as the instructional anchor of language teaching in the country for decades.

Table 5. Reasons for Favoring American English as the Pedagogical Standard in Philippine Schools

The results are indicative that there are teachers and students who regard AE as the most appropriate variety for international communication pushing PE to the periphery. This strengthens Tsuda (2008) claim that the Americanization of culture not only results in the replacement of languages but also the alteration of mental structures. It is still puzzling to know, however, why many of the respondents believe that AE is a superior variety.

The students' preferential option for AE may lead to what Tsuda (2008) calls “Linguicide' or the killing of other languages especially the weaker and the smaller ones. In this study, PE is seen to be the weaker variety. Hence, it could be argued that the Filipinos' attitudes toward AE might elevate the native speakers' variety to a prestige form.

The teachers' choice favoring AE also leads to another issue of whether they are really teaching AE and not the local variety. In a study by Pena (1997), it was found that teachers' manuals, which most of time are followed in its entirety, have features of PE. This study also cited an investigation by Penaranda (1990) stating that there are unusual lexical/syntactical constructions in the students' sentences which arguably, could be an outcome of what they learn from their teachers and exposure to a wide array of instructional tools. Authentic instructional materials e.g. newspaper articles, which are good sources of corpora for Philippine English studies, are also perused in the classrooms and as an effect, when students read or analyze such texts, they likewise learn PE and not purely AE.

The results also show that many English teachers have not recognized the advantages of choosing an endonormative nativized model proposed by Kirkpatrick (2007) have not truly sunk in on many English teachers. Perhaps, they have not realized that the choice of the local variety also redounds to their own empowerment in several ways – linguistic adequacy and possession of native familiarity with local cultural and educational norms. It is good to note, however, what Tupas (2006) asserts that “politically, they wish to hang on to the power of Standard English but, ideologically, they wish to move away from it by justifying their own position…” (p.178).

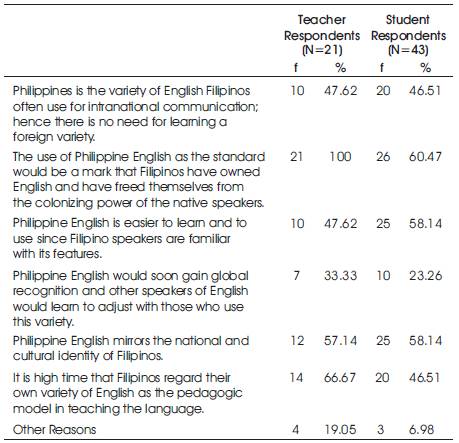

Table 6 presents the reasons why 21 language teachers and 43 student respondents favor Philippine English as the pedagogical standard in local schools. The data show that there is a preponderance of respondents who averred that the use of PE would be an indication that (i) Filipinos have owned the English language and have freed themselves from the hegemonic power of the native speakers; (ii) Filipinos have finally regarded their own variety of English as the appropriate pedagogical model in teaching the language; (iii) Filipinos look upon Philippine English as a mirror of Filipino culture and identity; and (iv) Filipinos have realized that there is no need for learning a foreign English variety since PE is used for intranational communication and that it is easier to learn because of the users' familiarity with its features.

Table 6. Reasons for Favoring Philippine English as the Pedagogical Standard in Philippine Schools

A number of respondents also gave other reasons for promoting Philippine English. The last three are forwarded by the students.

Analyzing the responses would lead one to conclude that the advocates of PE might have this in mind: Filipinos have their own local variety and no one has the exclusive rights over the English language. The promotion of PE could be a potent way for them to counterattack the Americanization of the Filipino culture through the English language as its representative colonial and global language (Kubota & Shin, 2008). Cognizant of language as the verbal expression of culture, the teacher and student respondents seem to believe that a culture's language has everything its speakers can think about and every way they have of thinking about things. It is, however, good to note that there is a small percentage of students who welcome PE as shown by their positive responses.

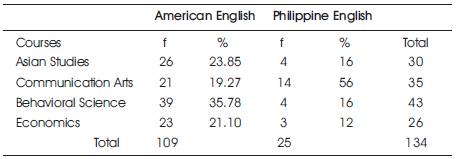

Table 7 presents the preferred English variety of the 134 students who have had a formal classroom lesson on the existence and features of Philippine English. The data clearly show that there is still a preponderance (109 or 81.34%) of students who would like to learn American English instead of Philippine English. Only 25 or 18.66% would rather use Philippine English as their norm in oral and written discourses.

Table 7. Students with PE Instruction's Preferred Variety of English (N=134)

The following condenses the students' responses to the open-ended question “What variety of English must be taught in all Philippine schools and why?”

Conversely, the respondents who opted for Philippine English have the following as their supporting reasons:

The data presented seem to have shed light on the students' language preference. Despite their formal introduction to PE, a majority still prefer AE. The students' remarks imply that the native speakers continue to be the yardstick for success, progress, and individual or collective growth. Magno (2004) believes that English is the Filipinos' 'widest window to the rest of the world' and is 'the most elegant tool for digging themselves out of the hole of underdevelopment'. Hence, the data show that there is still a preponderance of respondents who firmly believe that AE would give them better job opportunities abroad. It seems that the linguistic views of the respondents have been intensely reshaped by the 'soft power' (Nye, 1990) of the westerners and their desire to penetrate the global market for personal achievement.

The foregoing results suggest that popularizing PE is not easily realizable. Despite this difficulty, this paper proposes that there be 'de-hegemonizing agents' that would dilute the heightened aspiration of the Filipino language learners to sound like the native speakers of English. These de-hegemonizing agents include: (i) language teachers; (ii) educational institutions; (iii) government or state; and (iv) modern media.

The role of language teachers in the students' lives seems incalculable. Their influence is relatively enormous. Hence, they have the power to rework students' viewpoints. It is imperative that they engage themselves in professional and academic endeavors that would call for a critical evaluation of their own pedagogical practices that may eventually (re)shape the minds of their students. Completely turning down AE may not be totally possible but sensitizing learners to other options and emerging paradigms may be feasible if teachers themselves remain informed. Teachers who provide venues for critical questioning and understanding of language issues and phenomena are needed in the classrooms. They are expected to usher their students into reflective thinking and making thoughtful judgments.

The educational institutions where students spend nearly half of their lives also play an indispensable role in the de-hegemonizing process. Schools that penalize students for speaking in their dialects, assign specific campus spots as 'English Zones', and use English as their main come-on to attract a good number of enrollees should be (re)directed to look into their practices. Questioning the strict implementation of the English Only Policy as a potential hegemonizing reactant could be a good departure point for a change in language policies and reconsidering that schools are not venues for commercializing English like a basic commodity.

The government may also be prompted to look into its programs and policies. It is true that the biggest fraction of the national budget is allocated for educating and preparing the Filipinos for a productive life, but to pronounce that learning English be made mandatory just because it is the nation's powerful armory to penetrate the global village is another case in question. Honing the Filipino manpower's English proficiency because of the growing demand of workers abroad is a practice that needs to be reassessed. The training of graduates for manning call center industries and the infusion of 'call center English' (which basically promotes the use of Inner Circle varieties) in the formal curriculum is another set of propositions to be scrutinized for these might be a questionable move of the government which in the end may further reinforce the dominion of English.

Various forms of media also play a colossal role in the propagation of 'Americanism' in the Philippines. Filipinos from different walks of life follow fads by keeping abreast with the latest media broadcast. Hence, this sector may be reminded to practice social responsibility by promoting not what offshore nations, the United States in particular, offer. American culture is brought to the country through its language e.g. songs, movies and TV shows. Consequently, Filipinos desirous to be 'in' are compelled to learn English. The media portrayal of American way of life as a trendsetter and as a model to copy has spurred many to learn the English language. Many Filipinos are enticed by the local and foreign media to follow the 'American dream' by getting a lucrative job in the United States thus, without qualms they venture into the formal study of English. Therefore, the media is held responsible for balanced representation of both local and foreign cultures.

The de-hegemonizing agents cited above would have the power to make the nonnative speakers be one and not divided in their choice of language standard, this time favoring the local and not the outside norms. Their influence would help nourish the native variety whose evolution has ignited people to question their standpoint. It would take a long time and strenuous efforts before “linguistic liberation' set foot on the Philippine shores but the concerted efforts of all the de-hegemonizing agents might reshape the Filipinos' mental topography of the language. Indeed, it is quite easy to assign educational institutions, state, media, and language teachers de-hegemonizing roles, but reality would tell that acting as such would take a lifetime of acceptance and political and communal power. Unless these institutions are shaken by the glaring reality that many are still 'under the spell' of the native speakers and unless the Filipino speakers of English take a new and different stance, American English will still stay and prevail.

This study explored the prevailing perceptions of college students and language instructors toward the two main varieties of English that thrive in the Philippines – American English (AE) and Philippine English (PE) as well as their motives for learning and teaching the English language. This study has shown that a majority of the student and teacher respondents have similar reasons why English is taught and studied in the Philippines and that between AE and PE, AE remains as the privileged English variety. Although the data were culled from a relatively small population of respondents, it could be possible that students and teachers outside the study locale share the same unwelcoming attitude toward the Filipinos' native variety of English, are one in saying that learning AE is inevitable in this era of globalization, and believe that AE is the only ticket to the global village. It is also alarming to note that the respondents' mental landscape of the language is still largely shaped by the hegemonic control of English that is, English is power, and it offers its users with capital that can be used for amassing global investments. Hence, the acquisition of English proficiency serves as a potent vehicle for a person to satisfy his yearning for penetrating the world job market and eventually benefit from it in different ways. Indeed, this calls for a serious introspection to discern if this foreign language has to be taught and learned solely for that purpose.

This study has also shown that further nativization of English might be aborted if Filipinos continue to believe that the exonormative model should remain as the fulcrum of language instruction in the Philippines. To patronize something that has been existing for many years does not mean that it will infinitely stand part and parcel of the system especially when there are stemming debatable issues. The use of AE as a teaching model in the country is a practice that should be questioned. The Americanization of the Filipino culture has undoubtedly altered how Filipinos think and act in support to the foreign way of life. If this is not remedied, many Filipinos will continue to embrace not only the language of the 'modern-day colonizers' but everything about them and eventually, renouncing their own national and cultural identities.

The question, however, is how to design a pedagogical model using the native variety as its anchor. If AE continues to be a more popular choice, the next step is to develop a language curriculum that highlights PE as the primary medium of instruction. Unfortunately, until now even Filipino linguists still debate on what PE really is. Hence, after codifying PE, appropriate teaching and learning models should also be established. The involvement of teachers in the codification of PE, training of teachers on the use PE as the norm, sustained critical pedagogy, professional upgrading of language educators, a revisit of the current language curriculum and a review of instructional materials are of paramount significance. These will allow PE to flourish and perhaps gain fair recognition. This would also make students realize that AE is not the only variety of English but simply one of the many varieties of English across the globe. Inclusion of meaningful lessons that delve into features of PE must be provided to a wider population of students. These are small steps that can be done to further promote PE as a variety that is at par or even more appropriate than the native speakers'.

The momentum of PE advocates needs further (re)fueling to make more Filipino users of English not only shallowly aware but deeply sensitized that their own variety of English is acceptable, comprehensible, at par with the ruling model, and more importantly, could stand as 'the' language norm in the country. Thus, emboldening the four de-hegemonizing agents is indispensable in this process. Their collective efforts would result in 'positive brainwash' needed to help the Filipino users of English in liberating themselves from the shackles of hegemony perpetuated by English and its native speakers.