Table 1. Profile of the teacher-respondents (N=22)

This study examined the 'communicativeness' of 22 English language tests designed and administered by 22 English instructors from 22 different colleges and universities in the Philippines. Its key objective was to answer the question “How communicative are the language tests used in assessing students' competence (knowledge of the language) and performance (actual use of the language in concrete situations)?” The results indicate that there is a preponderance of test items that focus on language accuracy alone and not on the use of language in actual or real-life contexts. Further, the language examinations deemed communicative by the teacher-respondents themselves still use discrete-point, paper and pencil, and decontextualized test items. Thus, it seems that the perused examination items lack the requisite elements or qualities that make a language test genuinely communicative. The results also suggest that language teachers' assessment practices must be further (re)examined to ensure that they do match the approach that underpin language instruction i.e. they must ascertain that the learners are taught and tested the communicative way.

Language education in the Philippines is believed to be in adherence to the most recent and popular buzzword in English language instruction - the Communicative Approach. A large body of Literature says that the Communicative Approach (CA henceforth) accentuates the importance of using a language rather than only learning its rules. Richards and Rogers (2001) assert that by using CA, language teachers are able to develop the learners' 'communicative competence' (Hymes,1972) and 'communicative language ability' (Bachman, 1990) consisting of both knowledge of a language and capacity to use or to execute that knowledge in appropriate and contextualized communicative language situations. They also describe CA as “a diverse set of principles that reflect a communicative view of language and language learning and that can be used to support a wide variety of classroom procedures” (p.172). This approach endeavors to equip the learners with the needed language skills to effectively engage in varied and meaningful communication situations. Hence, it is a potent instructional anchor that could very well support the present-day language teaching practices.

As a result of embracing CA as the instructional paradigm that underpins the present language instruction in the country, it goes without saying that the students who are taught the 'communicative way' are also assessed the 'communicative way'. Put more succinctly, there should be no mismatch or incongruence between how the learners are trained in the discharge of communicative functions and how their performance is evaluated. Put in another way, if the very aim of language teaching is to develop the communicative competence of the learners, the effectiveness of classroom instruction must be established via appropriate communicative language testing instruments.

It is important to note Brown's (2003) argument that the language testing field has started to concentrate on developing communicative language-testing tasks. As a consequence, when teachers design classroom-based assessment instruments, they are expected to apply their knowledge or technical knowhow on the rudiments of designing communicative language tests, task-based language tests, authentic tests, integrative tests, and performance-based tests. To McKay (2006), Weigle (2006), Brown (2005), Nunan (2009) and the present writer, strongly believe that these assessment modalities complement the communicative approach to language teaching.

This study therefore takes a critical look at the current English language testing practices at selected Philippine universities to see how much evidence there is to support the claim that language teachers test language learners communicatively. Basically, it answers the question “How communicative are the language tests used in assessing students' competence (knowledge of the language) and performance (actual use of the language in concrete situations)?” Put in another way, this study examines the 'communicative qualities' of the assessment tools developed and used by the teacher-respondents themselves. The present study also addresses the issues that stem from the implementation of communicative language testing and potential problems that restrain language teachers from testing communicatively. The results of this investigation may also prompt language teachers to reflect on their current testing practices and to further engage in communicative language teaching and testing training in case there is still a need for it.

CA could be regarded as an offshoot of language practitioners' discontentment with the audio-lingual and grammar-translation methods of foreign language instruction. It is the reaction against the view of language simply as a set of structures. It considers language as communication, a view in which meaning and the uses to which language is put play a central part (Brumfit & Johnson, 1979). CA advocates firmly believe that the ability to use language communicatively entails both knowledge of or competence in the language and the ability to implement or to use this competence (Razmjoo & Riazi, 2006).

Throughout the years, an overabundance of viewpoints has been forwarded to shed more light on what CA really is. Now, it has been proved that the communicative approach to second language teaching is anchored on various disciplines and inter-disciplines of psycholinguistics, anthropological linguistics, and sociolinguistics that put premium on the cognizance of social roles in language (Cunliffe, 2002). To Richards and Rodgers (2001), CA commences from a theory of language as a communication. They emphasize that:

Similarly, Murcia (2001) describes CA as a language teaching philosophy that views language as a system of communication. She highlights though that in CA,

The most popular literature on CA, however, is forwarded by Canale and Swain (1980). Fundamental to their view is Hymes' (1972) notion of 'communicative competence.' They underscore the interactive processes of communication and regard language as a system for the expression of meaning. They identified the four dimensions of 'communicative competence' which include:

Putting the above mentioned more concisely, the very goal of CA is to allow learners to use the language appropriately in a given social context through 'authentic' communicative activities. Thus, this necessitates a creation of 'real-life' communicative situations that prod learners to use the target language in communicating with others as they perform varied classroom activities that approximate actual interactions.

Kitao and Kitao (1996) posit that language testing has customarily taken the form of assessing knowledge about language, usually the testing of knowledge of vocabulary and grammar. However, it appears that the current language testing field has started to concentrate on designing communicative language-testing tasks. Possibly, this move is prompted by Nunan's (2009) stance that, “A fundamental principle in curriculum design is that assessment should be matched to teaching. In other words, what is taught should be tested” (p.136). He further argues that communicative language teaching requires communicative language testing. To him, “learners should be asked to perform an activity that stimulates communicative use of language outside the testing situation” (p. 137). It is in the same vein that Weir (1990) points out that, “Tests of communicative language ability should be as direct as possible i.e. they must attempt to reflect the 'real life' situation and the tasks candidates have to perform should involve realistic discourse processing” (p. 12).

To Boddy and Langham (2000), communicative tests “are intended to provide the tester with information about the testee's ability to perform in the target language in certain context-specific tasks”(p.75). To them, the following are the fundamental features of communicative language tests:

Their views support the notion that in communicative testing, the administration of authentic and performance-based assessments is necessary. In this type of assessment, language skills are assessed in an act of communication and the test-takers' responses are extracted in the context of simulations of real-world tasks in realistic contexts (McNamara, 2000).

To Canale and Swain (1980) communicative teaching and testing takes into account the following principles:

Brown (2005) also underscores that in communicative testing, interactive tasks must be clearly evident. These tasks involve the learners in actual performance of the behavior the tests purport to measure. Hence, testees are assessed in the act of speaking, requesting, and responding or in their ability to integrate the four macroskills. He also cites interview as a good example of an interactive task. He argues that, “If care is given in the test design process, language elicited and volunteered by the student can be personalized and meaningful, and tasks can approach the authenticity of real-life language use” (p.11).

Harrison (1983) adds that communicative tests must:

Phan (2008) likewise stresses that the following principles be observed in the design of communicative language tests:

CONSTEL English (1999), a telecourse for teachers of English in the Philippines, proposes the following principles in constructing communicative reading, writing, listening, and speaking tests:

The foregoing therefore implies what Ireland (2001) asserts that, “With communicative language courses designed to engage students in real-life communication activities, and aiming to actually enable students to use the language in real-life situations, it is reasonable to suppose that testing design should be based on evaluating these communicative skills” (p. 33). Phan (2008) adds that communicative language tests which cover the four language skills of listening, speaking, reading, and writing, must be principally designed on the basis of communicative competence. Further, assessments must complement instructional practice, mirror the defining traits of language learners and generate substantial data (Gottlieb, 2006). Hence, it is imperative that the language assessment tools employed to gauge learners' performance in the target language match the philosophy or approach that underpin classroom teaching.

Based on the aforementioned, it could be concisely deduced that communicative test design must be entirely anchored on a communicative view of language. As what Phan (2003) posits, “A communicative test offers communication meaningful for learners in real-world contexts where students experience and produce language creatively using all four language skills of listening, speaking, reading, and writing” (p. 9). Hence, even in testing, learners must engage in assessment tasks that call for their ability to act and interact in certain communicative contexts that resemble communication situations outside the four walls of the language classrooms. Finally, communicative tests must measure how much the learners are able to use their knowledge of language in varied communicative situations than demonstration of their knowledge in isolation.

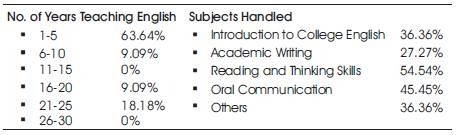

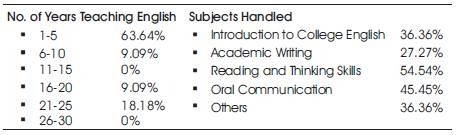

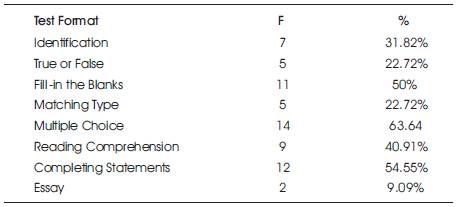

Twenty-two English instructors participated in the study. As shown in Table 1, a majority (63.64%) of the respondents are relatively new in the language teaching profession. Very few (9.09% and 18.18%) have been in the field for more than 5 years and 20 years respectively. In addition, the respondents taught different English courses at the time this study was conducted. It is necessary to note, however, that 36.36% of the respondents were asked to teach non-English subjects e.g. philosophy, logic, and history.

Table 1. Profile of the teacher-respondents (N=22)

A survey questionnaire was administered to 22 college English instructors from 22 different colleges and universities in the Philippines. The primary objective of the questionnaire was to elicit pertinent personal data about the respondents and information about their language assessment beliefs and practices.

The respondents were requested to provide the most recent major language tests they designed for and administered to their own students. Hence, 22 tertiary English examinations in general English courses like Introduction to College English, Reading and Thinking Skills in English, and Oral Communication were collected.

This descriptive study employed both qualitative and quantitative analyses. The respondents' answers to the questionnaire were tallied and analyzed through frequency counting and percentage computation. To provide analytic claims, the sample tests were qualitatively examined vis-à-vis communicative approach to language testing principles. The tests of grammar, vocabulary, reading ability, and oral communication were carefully examined by identifying their usual expectations from the test-takers, types, stimuli, item-response format and item-elicitation format. Sample items were culled and thoroughly inspected to determine their communicative qualities. The analysis was guided by the communicative teaching and testing principles presented in the previous section.

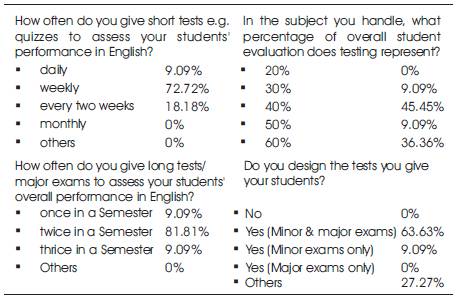

It could be gleaned from Table 2 that students' language proficiency is regularly assessed by a majority (72.72%) of the respondents through weekly short tests. Major examinations are also administered twice every semester by 81.81% of the informants. This is done since a large fraction, usually 40% or 60%, of the students' grades is derived from their scores in language tests. The data also show that more than half (63.63%) of the teachers design their own minor and major examinations. In some cases however, departmentalized examinations are used.

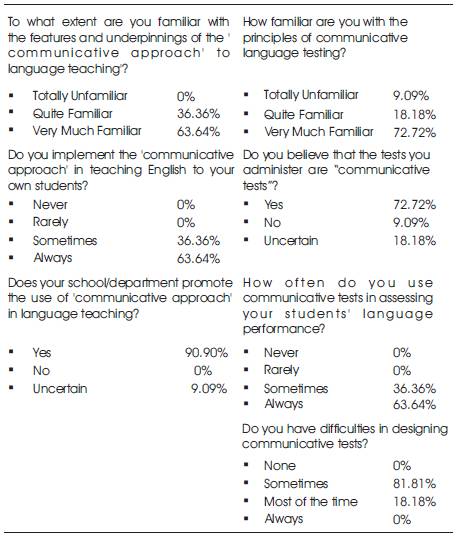

Table 3 shows that there is a preponderance (63.64%) of teachers who are familiar with the theories that underpin CA and who always implement these theories in the language classroom. The data also reveal that many (90.90%) of the institutions where the respondents are presently affiliated support their language departments in promoting the use of CA. In addition, a majority (72.72%) of the respondents are much familiar with the communicative language testing principles, 63.63% believe that they always assess their students' language performance communicatively, and 72. 72% deem that their own tests possess communicative qualities. The data also show that 81.81% still encounter difficulties in designing communicative language tests.

It is precisely because of the abovementioned findings that the present study investigated the communicative qualities of the examinations used and provided by the respondents themselves. As stated earlier, a majority of the informants believe that they teach communicatively and the tests they developed are certainly communicative. This assumption propelled the present writer to examine their language tests with the end goal of describing or establishing teaching and testing connection or perhaps, possible teaching and testing mismatch in the teachers' respective classrooms.

Table 4 presents the common test formats utilized in the sample examinations. It can be deduced that 'traditional' test formats like multiple choice, fill-in the blanks, and completion of sentences are still prevalent in the language tests. Further, the same table suggests that teachers often resort to objective written examinations with items that can be easily graded or scored. Only two out of the 22 sample tests used essay tests, perhaps because it requires so much time and effort to be graded in an objective manner.

Table 2. Teacher- respondents' language testing practices (N=22)

Table 3. Teacher- respondents' communicativelanguage testing beliefs (N=22)

Table 4. Common test formats used in the sample examinations (N=22)

A closer look at the examinations also shows that there are other test formats used e.g. spelling, sentence transformation, diagramming, transcription, paraphrasing, outlining, situational analysis, sentence formation, and word definition. However, it is questionable if these subtests could really stand as solid bases for assessing the learners' communicative performance. To Boddy and Langham (2000), “One way of obtaining a fuller sample of the candidate's language would be to include as many tasks in the tests as possible” (p.80). The analysis of the sample tests indicates that language testers still rely on and limit themselves to traditionally available assessment tasks that require test-takers to simply write short responses or choose the correct aswers from available options which may not successfully give a better picture of the learners' overall communicative competence.

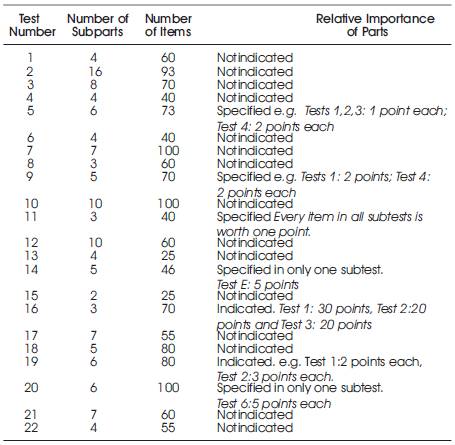

Table 5 shows the organization or salience of parts of the sample language tests. The data reveal that a classroom-based language test would often have a number of subparts covering various topics discussed within a certain instructional period. These subparts are clearly demarcated or labeled using letters or numbers. In some tests, the descriptive information is provided in the labels e.g. “English Consonants and Vowels”, “Reading Comprehension” and “Communication Process” and each has specific expectations from the test-takers. In addition, the subtests also use a variety of test formats. Hence, it is not surprising to find a multiple-choice test as the first subtest and fill-in the blanks as the next. In other words, a language test may consider itself as a battery of tests. It is not clear, however, if the subtests are typically of varying degrees of difficulty and sequenced from the easiest to the most challenging.

The same table also shows that the number of items in a language test could be as few as 25 items or as many as 100 items. A closer look at the samples also indicates that the tests are not always weighted equally. It is not usual to see the relative importance of the items in each subtest that is, the testers rarely indicate how the items in a subtest are weighted. In some cases, only the subtests total points is stipulated e.g. Test 1: 30 points, Test 6: 5 points, and not the specific criteria on how the student's answers will be judged. This practice is criticized by Bachman (1990) by stating that if the relative importance of the parts is overtly indicated, the testees will be given an opportunity to adapt their test-taking strategies so they could give more time and effort in answering the sections deemed more important. Cunliffe (2002) suggests that marking criteria should be clearly defined before grading ambivalent items so that subjectivity will be minimized or reduced. It must likewise be noted that the time allocated for each of the subparts is hardly found in the tests. Perhaps it is assumed that test-takers will be able to finish the test in 1 hour or 1 ½, the usual time allocated for each course examination in many Philippine schools.

Table 6 presents the grammar test items prevalent in the samples. It is evident that the test input which according to Bachman (1990) “consists of information contained in a given test task, to which the test taker is expected to respond” (p.125) is predominantly visual or written. Put more succinctly, the perused grammar tests are primarily paper and pencil tests. The table also shows that there is a preponderance of fixed item-response format e.g. true/false, multiple choice, and matching items and structured response format e.g. identification and completion, transformation items, and word changing items. Moreover, there is a very small number of open-ended response formats e.g. sentence composition and writing paragraphs. In other words, a majority of the test items require merely selecting the correct answer from several options or the identification of incorrect alternatives, as in the case of identifying errors in sentences.

Table 5. Organization or salience of parts of the sample language tests

A closer look at the samples would imply that there are still test items which simply ask testees to identify the function of a word and the type of a given part of speech and to distinguish sentences from phrases. Very few used 'contextualized' multiple-choice and gap-filling grammar test items. The sentences serving as test stimuli or inputs are 'isolated or unrelated sentences' that do not form a coherent and logical stretch of discourse. They are usually 'de-contextualized' multiple-choice and gap-filling grammar tests. They simply require learners to exhibit competence by responding to questions with no specifiable context or sequence and do not signify successful filling of any information gap (Ireland, 2001). Put in another way, the samples chiefly use 'discrete point tests' which Bachman (1990) describes as “tests which attempt to measure specific components of language ability separately” (p. 128) and tests that “break language down, using structural contrastive analysis, into small testable segments...to give information about the candidate's ability to handle a particular point of language” (Boddy & Langham, 2000, p. 76).

The data seem to show that to this day, test designers and writers resort to discrete-point testing despite the contention that discrete-point tests “are the least favored in current thinking about communicative competence” (Hurley, 2004, p. 67). It appears that they have not completely realized that a sentence in isolation is often meaningless from the communicative perspective (Shimada, 1997) and that “language can not be meaningful if it is devoid of context” (Weir, 1990, p. 11). Perhaps, Thrasher's (2000) argument that its use has three major drawbacks namely: (i) performance on such items does not simulate the way students will have to use language in the real world; (ii) they produce negative washback since they give the test takers the wrong notion that language is composed of individual and independent parts that can be learned apart; and (iii) such items are claimed to be unnatural because of the reduced level of context which have not sunk in on many language test developers.

The results are also reflective of Nunan's (2009) position that indirect assessment, an assessment mode where there is no direct relationship between performance on the test and performance outside the classroom, remains the usual practice because of convenience that is, these tests have the advantage of being easy to mark and being able to cover an array of grammatical points quickly. Shimada (1997) stresses that “what is needed and to be measured is the ability to deal with discourse or string of sentences in the context of real situations” (p.16). This provides the testees more context and, if the text stimuli are meticulously chosen, is also much more interesting than reading isolated or individual, uncontextualized sentences. In other words, when testing grammatical competence, it is imperative that students be provided not with isolated sentences but with stretches of language above the sentential level since grammatical knowledge is involved when examinees understand or produce utterances that are grammatically precise and contextually meaningful (Purpura, 2004). Since learners are propelled by tests, these can be utilized to highlight what grammar intends to do for them (Lee & VanPatten, 2003).

Table 7 presents the typical vocabulary tests used in the samples. The data reveal that there is also a preponderance of written item-elicitation format and fixed item response format in the 22 examinations. Multiple-choice vocabulary tests e.g. guessing meaning from context and matching items are also the usual choice of the test writers and very few utilized open-ended vocabulary tests. Hughes and Porter (1983), however, emphasize that this kind of choose-the-correct-answer format in fact limits itself to merely testing recognition knowledge. It is less likely to assess students' real ability to use the language productively and communicatively.

Further analysis of the sample items likewise implies that assessors rarely test all the four types of vocabulary namely: (i) active speaking vocabulary or a set of words that a speaker is able to use in speaking; (ii) passive listening vocabulary or words that a listener recognizes but cannot necessarily produce when speaking; (iii) passive reading vocabulary or words that a reader recognizes but would not necessarily be able to produce; and (iv) active writing vocabulary or a set of words that a writer is able to use in writing (Kitao and Kitao, 1996). It appears that the sample examinations usually assess only passive reading vocabulary since they are paper and pencil tests and because they rely heavily on reading.

It is also important to cite that there are vocabulary items in the samples that require learners to give the meaning of words that are isolated lexical units or are not used in any specific context. It must be noted that vocabulary is best assessed in an integrated way within the context of language use or through language use in language tasks (McKay, 2006). Read (2001) argues that, “The contemporary perspective in vocabulary testing is to provide a whole-text context rather than the traditional one-sentence context” (p.11). Hyland and Tse (2007) assert that, “Learners should engage with the actual use of lexical items in specific contexts if they are to be successful language users in the academic environment or elsewhere” (p. 10). A sound vocabulary test should therefore present the words to be tested in similar way as possible to what will be encountered in the real world and the test taker need not guess which meaning of a word the test writer had in mind (Thrasher, 2000).

Table 8 presents the reading tests predominant in the sample examinations. A closer look at the data shows that the reading tests likewise often use multiple-choice and fixed item-response format in their attempt to accurately assess the learners' reading ability. Although there are open-ended questions e.g. outlining and summarizing a four-paragraph essay, these tasks are hardly made communicative since realistic reasons for doing such a task are not made explicit. It is also surprising to see a summarizing test that has no clear instructions as to how answers will be judged and how the testees are going to go about it.

Table 8 also shows that testers often use comprehension questions to test whether students have understood what they have read. These questions, almost always, are found at the end of a paragraph or passage clipped from an unknown source. However, in everyday reading situations, readers have in their mind a purpose for reading before they start. Knutson (1997) believes that, “In both real-world and classroom situations, purpose affects the reader's motivation, interest, and manner of reading” (p.25). Thus, to make reading assessment more authentic, the test-takers must be allowed to preview the comprehension questions which would call for conspicuously placing the questions before and after a reading passage. It is also suggested that in order to test comprehension appropriately, these questions need to be properly coordinated with the reason or purpose for reading. If the very objective of the test-taker is to find particular information, comprehension questions should center on that information; if the purpose is to recognize an opinion and identify the arguments that support it, comprehension questions should ask about those aspects as well (The National Capital Language Resource Center, 2004). In addition, it may even be beneficial to explicitly specify to the respondents the type of reading expected from them (Cohen, 2001).

A closer look at the sample tests would also show that there are no authentic texts that serve as reading test inputs. It must be remembered that in designing communicative reading tests, authentic materials from the testee's environment should be used since they provide valuable texts for assessment (McKay, 2006). Examples of these authentic materials include weather reports, news articles and brochures, timetables, maps, and other informational materials ubiquitous in the learner's environment. The tests chiefly used short paragraphs or passages culled from different print and online sources as reading test stimuli. The longest text for comprehension in the samples is a four-paragraph essay and the questions that follow merely asked for the main idea of the essay and meaning of a number of words assumed difficult or unfamiliar. Knutson (1998), however, argues that when testers opt to use longer texts, the testees can be asked to recognize the discourse features of the text or text types and concentrate on pragmatic issues of register and audience and examine the lexical ties and the syntactic devices used to establish topic and theme.

Further analysis of the reading tests also shows that the test stimuli are not of the same theme. In other words, they are unrelated or unconnected passages or paragraphs talking about different topics. At the end of these paragraphs is a typical task of answering written comprehension questions and test-takers simply have to pick the right answers from a given set of options. No other form of responses is required. Swain (1984), however, suggests that to make reading tests communicative, they should be turned into tests with a 'storyline' or thematic line of development. In other words, there must be a common theme that runs throughout in order to assess contextual effects (Cohen, 2001). Brill's (1986) (as cited in Cohen, 2001) study on completing a communicative storyline test that involved five related tasks reveals that the respondents prefer communicative reading tests since they are more creative, they allow expression of views while working collaboratively with others and investigation of communication skills apart from reading comprehension.

A more profound implication of the analysis of the test items is that, since the goal of language instruction is the development of communicative competence, reading tests should complement or substitute traditional tests with alternative assessment methods that provide more reliable measures of reading progress toward communication proficiency goals. As an example, the testees may be given a task in which they are presented with instructions to write a letter, memo, summary, answering certain questions, based on information that they are given (Kitao & Kitao, 1996) or drawing a picture based on a written text, reconstructing a text cut up into paragraphs, or, in pairs, reading slightly different versions of the same story and discovering differences through speech alone. Knutson (1998) posits that these tasks, although not necessarily real world, are still communicative; importance is placed on digesting a text in order to get something accomplished. It would also be significant if test-takers are given appropriate post-reading tasks that mirror real-life issues to which testees might put information they have assimilated through reading (The National Capital Language Resource Center, 2004). Testers must keep in mind that “a good reading test will indicate students' level of communicative competence, their breadth of knowledge, and their ability to actively apply that knowledge to learning new things” (Hirsch, 2000, p. 4).

Table 9 presents the usual types of speaking tests found in the sample examinations. It could be gleaned that even the speaking tests developed by the language teachers utilize written stimuli and written item-elicitation format. The learners are also tested on lessons like conversational maxims, qualities of a good speaking voice, and repairing communication breakdown using multiple-choice tests in which they have to respond by writing their answers without listening to any live or taped aural input. While it is possible that other tests of speaking have been done outside the examination schedule, it is quite puzzling why the sample tests include tests of pronunciation, stress, syllabication and level of usage that require written and not oral responses from the test-takers. In other words, the test items e.g. copying the syllable that bears the longest accent, underlining letters that sound in the same manner, and completing a chart of the English consonants and vowels do not elicit oral production in the target language. An examination of the items would also show that when testers assess pronunciation, they are more concerned with the articulation of words in isolation and not with longer stretches of oral discourse.

Further analysis of the tests indicates that indirect test, which for speaking would mean any test that is not a spoken one; still seem prevalent in many language classrooms. McKay (2006) comments that, “Oral language assessment is often avoided in external testing because of practical considerations” (p. 177). This practice contradicts Hughes' (1989) assertion that the abilities testers would like to develop should be tested; hence, if test developers target oral ability, they should test oral ability as well. Otherwise, they are depriving the learners opportunities to use the language in the way they are supposed to (Heaton, 1988). It should also be noted that “good practice calls for using varied measures of speaking, such that for each learner, more than one type of speaking is tapped” (Cohen, 2001, p. 533). It also appears that the test of speaking used by the language teachers rarely address the learners' communicative language ability in terms of sociocultural, sociolinguistic, and strategic competence. The different levels of speaking , namely, imitative, intensive, responsive, interactive, and extensive are not also comprehensively covered by the sample examinations.

CA promotes that teachers engage learners in meaningful activities such as information-gap and role-play activities (Nunan, 1999). Thus, learners must also be tested using these modalities. It is quite apparent, however, that the perused speaking tests still rely on traditional paper and pencil tests. There are no provisions for interactive conversations and exchanges that involve oral production in the target language. Perhaps, this is caused by Ireland's (2000) position that language testers are constrained to administer speaking tests because of big class size and limited time for testing and subjectivity in grading students' performance. Testers, however, must keep in mind that assessment tasks must generate language samples with sufficient depth and breadth so that they can make sound judgements as to how students fare and provide them with meaningful feedback on their performance. Whether written or spoken, tests of communicative performance are expected to be highly contextualized, authentic, task-based, and and learner-centered. It is quite unfortunate that most of the speaking test items perused in the present study failed to possess these important qualities of a true communicative speaking test.

Further analysis of the sample examinations also implies that appropriate listening and writing tests are barely used. This seems to violate the principle of integrative testing purporting that a good language test must cover all the four macro-skills of listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Tests of discourse, strategic, and sociolinguistic competencies are hardly found in the samples as well. The language tests used are predominantly tests of linguistic or grammatical competence. This signifies that the four dimensions of communicative competence that test-takers must possess are not substantially and holistically addressed. Moreover, the examinations tested competence rather than performance i.e. they tested knowledge of how the language works rather than the ability to use it.

It is therefore necessary for language teachers to examine their current testing practices to ensure that their design clearly and unquestionably aims at testing the skills developed in the 'communicative classrooms' and that the tests are integrated, contextualized and direct, and cover not only syntactic but also semantic and pragmatic levels of a language. They have to be reminded that “tests of communicative language ability should be as direct as possible i.e attempt to reflect the 'real life' situation, and the tasks candidates have to perform should involve realistic discourse processing” (Weir, 1990, p. 12).

The considerations in testing communicatively outlined in the previous section must be taken into account to evolve appropriate assessment tools that best suit one's class or institution. A good reading test for example, may require the test-takers to write a creative response to an article or a passage which would serve as a more potent gauge of how much they understood it. Through this, the writing skills of the students may also be assessed. A taped dialog may also be given to check the students' listening ability and to require the testees to orally identify and repair possible communication problems by proposing sound and doable suggestions. In doing so, the other skills are also tested and are not left out. Although it would appear that communicative test “is a form of testing which, like any other, has problems associated with it, ... it is the responsibility of researchers and teachers to endeavour to find solutions to those problems” (Boddy & Langham, 2000, p.81).

The present writer believes that big class size, limited time allotted for testing, absence of a clear set of marking criteria, perpetuating traditional testing practice, and personal inhibitions due to 'practical' reasons seem to restrain teachers from utilizing communicative language tests. To address the first three, Ireland (2000) suggests that regular monitoring and evaluation be conducted, large classes be given communicative tests over two class periods in which one group does listening or writing tasks while the other takes a speaking test, and clearly defined and realistic targets and criteria for evaluation must be established. To address the last two, this study suggests that midterm and final term examination practices be reviewed since 'seasonal' testing might not give an accurate impression of what students can actually do with the language especially if the instruments used do not match the language philosophy to which students are exposed, that the grading system that assigns the biggest weight to examinations must be looked into since students would more likely fail in the course if they obtain poor marks in the tests that are, in the first place, inadequate in describing their own performance in the language classroom, and that practicability be not taken as the main reason for veering away from designing communicative language tests. The use of traditional tests because they are are easier and faster to mark puts the learners at the disadvantage since their communicative competence is not properly unearthed through appropriate testing procedures. When all these are done, possible mismatch between teaching and testing may be avoided.

Although limited to only 22 examinations, this study has shown that there exists a disparity between how the students were taught and how they were tested. The teachers involved in the study view language as a system of communication yet their tests seem insufficient and weak in assessing the overall communicative performance of the students in actual life contexts. Therefore, possible means to address the problems and issues that accrue to communicative testing should be exhausted through collaboration, critical pedagogy, and research. Doing simple test analysis may be a good starting point for the teachers to establish the communicativeness of the the test items and their testing procedures. The tests purposively examined in this investigation may not be communicative enough but they can still be used as takeoff points as assessors design tests that truly complement their instructional approach. The bank of test items analyzed in this study may be used by the teachers themselves as they add more 'communicative ingredients' to the examinations they administer.

The communicative approach to second language teaching has resulted in constant re-evaluation of testing procedures. Hence, communicative language tests are not anymore viewed as traditional written exams that principally aim to test the learners' ability to manipulate grammatical structures of a language (Cunliffe, 2002). The main implication that the CA model has for communicative language testing is that since there is a theoretical dissimilarity between competence and performance, the learners must be assessed not only on their knowledge of language, but also on their ability to put it to use in varied communicative situations (Canale & Swain, 1980). Ideally, testing is a continuous classroom endeavor that strives to give a valid and clear description of what language learners can actually do in real-life situations.

An analysis of 22 sample language tests was done to detect if the students who are believed to have been taught the communicative way have also been tested in the the communicative way. It is not fair, however, to sweepingly say that there is a total mismatch between the instructional approach of the teachers and their assessment practices and that all the sample tests analyzed in the present study are not in any way communicatively crafted and are developed based on unprincipled design. Perhaps, they simply lack the other requisite elements or features that make a language test genuinely communicative.

The use of discrete-point, paper and pencil, and decontextualized test items has been proven to reduce the communicative qualities of the sample tests. In fact, these types of tests have little if any authenticity to the learners' world (McKay, 2006). Morrow (1981) adds that answers to tests should be more than simply right or wrong, more than choosing the appropriate answers from a medley of choices; tests should successfully uncover the quality of the testee's language performance.

While as of this time, it may not be totally unavoidable for a language teacher to use these traditional modes of assessments because of contraints like class size, time allocation, and other practical reasons, the utilization of communicative, authentic, performance or task-based, and integrative tests to complement or totally replace old testing tools remains well advised. Tests that exhibit real communicative functions do play an indispensable role in the language classrooms since students are not evaluated solely on accuracy but also on other communicative dimensions like fluency (Freeman, 1986).

The present study has shown that many of the test items in the samples focus on language accuracy alone and not on the use of language in actual or real-life context. Although it is suggested that a similar investigation involving a larger population of respondents and a bigger sample test item banks be conducted, the present study has affirmed Nunan's (2009) assertion that the present-day examinations are still built on traditional paper and pencil tests of grammatical knowledge. Thus, language testers must be constantly reminded that learners must be exposed to more situational assessment formats to effect natural use of the target language. Recent studies have shown that multiple choice and short answer tests are not communicative since the ability to select one word from an array of choices is entirely different from the ability to use them in meaningful utterances that not only convey a purpose but also appropriate to a specific context (Ireland, 2000). Hence, those who are responsible for designing communicative tests should be more interested in what the learners can do with the language and not only in what knowledge of the language they possess (Shimada, 1997).

Finally, it must be stressed that assessment has the power to change people's lives (Shohamy, 2001). Thus, educators are constantly challenged to make sound decisions about the students success or failure by planning, gathering, and analyzing information from varied sources to arrive at results that prove significant to teaching and learning (Gottlieb, 2006). Assessment tools must be carefully designed to ensure that they do match the approach that vertebrate language instruction. In other words, the students should be tested the way they are taught. The selection of assessment tasks and procedures should be handled with utmost forethought since incorrect decisions could put the learners at a disadvantage (McKay, 2006).