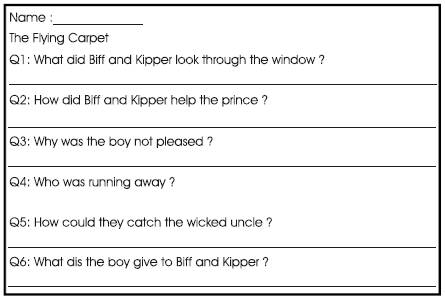

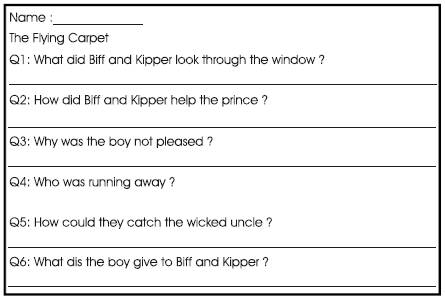

Figure 1. Reading Passage

This collaborative action research aimed to explore some classroom-based assessment strategies to assess the reading skills of young children. This article presents the findings of the pre-intervention stage as part of an action research study where a teacher's perception and practice of assessing the reading skills of young learners were explored. The research participants included one early years' English Language teacher along with four students of grade II as a focused group. Data were generated through observations, semi-structured interviews, document review and a reflective diary maintained by the researcher. The findings revealed that a teacher's belief and perception influenced her choice of assessment strategies and also her practice of reading assessment in the classroom. The teacher believed that assessment led to perfection in the reading skills of young learners. For her, assessment was undertaken to polish the weak areas of children's reading. Once the weak area was identified, children needed rigorous practice of the specific area until they gained mastery in it. Moreover, it was found that the teacher applied multiple assessment strategies to assess the reading skills of her children but she had her own perceptions and purposes for choosing a particular assessment strategy which may or may not be supported by the research and literature on reading and assessment of young learners. Based on the findings, recommendations are made for teachers, teacher educators and early childhood practitioners.

The aim of this study is to explore how the reading skills of young children of class II are assessed through Classroom-Based Assessment (CbA) strategies. This article reports the findings specifically from the pre-intervention phase that explored a teacher's perception and practice of assessing the reading skills of young learners. The following research questions guided this study:

In the early years, teachers play a pivotal role in shaping the literacy experiences of young children (Rosemary & Abouzeid, 2002). Teachers can assess students through a variety of ways to make decisions about their performance (Airasian, 2005). The purpose of assessment is clearly stated in the National curriculum of Pakistan for Early Childhood (2007). in that assessment is undertaken to evaluate a child's existing performance and to help make plans for future learning experiences for the child. In the context of Pakistan, my observation informs me that teachers are unable to fulfill the purpose of assessment probably because they are not aware of a variety of CbA strategies which can elicit a rich picture of students' reading development. In the school where I taught, teachers relied mostly on sporadic observations and read aloud to gather information and make decisions about children's reading development. Therefore, I felt a dire need to explore different CbA strategies that could be employed by teachers to assess the reading skills of young children.

. (2007). in that assessment is undertaken to evaluate a child's existing performance and to help make plans for future learning experiences for the child. In the context of Pakistan, my observation informs me that teachers are unable to fulfill the purpose of assessment probably because they are not aware of a variety of CbA strategies which can elicit a rich picture of students' reading development. In the school where I taught, teachers relied mostly on sporadic observations and read aloud to gather information and make decisions about children's reading development. Therefore, I felt a dire need to explore different CbA strategies that could be employed by teachers to assess the reading skills of young children.

The importance of assessing reading skills is crucial during the early years of a child's learning because parents are mostly concerned with reading skills development as compared to focusing on the other school subjects (Al-Momani, Ihmeidehb & Abu Naba'hc, 2010). If children are unable to read and comprehend the text, their performance will be affected in other content areas such as Science and Mathematics (Brown & Broemmel, 2011). This study is pitched at the early years' (0-8 years) context where attention is given to children's early literacy development which includes progress in reading skills. The National Curriculum of Pakistan for English Language. (2006). states the two standards of reading and thinking skills:

Reading remains a consistent part of the English language curriculum throughout the school years since the pre-level. In order to meet the standards stated earlier, it is important to align assessment with the process of teaching and learning. This cannot be done unless a teacher has access to and an awareness of various assessment strategies. Thus, through this study, I worked in collaboration with a teacher and explored some CbA strategies to assess the reading skills of young learners.

Research into the assessment of Young Language Learners (YLLs) has been a central focus in the last decade (McKay, 2006). A few studies have been conducted in teachers' assessment practices of YLLs in contexts such as Europe where the work of Rea-Dickins and Gardner (2000) has provided insights about the assessment of YLLs. They have explored formative assessment in elementary classrooms, studied the quality of teacher assessment as well as the issues and challenges related to the assessment being carried out. Their detailed analyses of teacher interactions and assessment procedures are considered seminal in developing a more holistic understanding of the assessment of YLLs. Findings of Rea-Dickins and Gardner's (2000) study suggest that it is inappropriate to place classroom-based assessment at a low-stake level. Such assessments could serve an important purpose in making more informed decisions about young children's progress in the classroom. Moreover, in Italy, a two-year pilot-study conducted by Gatullo (2000) reported that practitioners did not make effective use of the information they collected for assessment (formative) purposes. She also found that teachers did not ask children about the way they thought in the language classroom even though it was considered to be important in the specific subject. Furthermore, in Taiwan a few studies have been conducted which focus on the use of multiple assessment strategies to assess the language development of YLLs (Yang, 2008; Chan, 2007). These studies established that teachers of YLLs considered multiple assessment strategies more effective than paper-pencil tests and also believed that those alternative strategies could provide a holistic picture of children's development in the early years. These research studies were found to be promising in relation to teachers' assessment practices of YLLs in that the teachers used a range of assessment strategies. In addition, these studies (McKay, 2006; Chan, 2007; Edelenbos & Kubanek-German, 2004; Gatullo, 2000) also highlighted a number of factors such as teachers' beliefs, assessment education, and teachers' perceived self-efficacy which were critical in contributing to the differences in their assessment methods.

For assessing YLLs, Classroom-Based Assessment (CbA) is considered to be favourable in terms of gaining information about the children's language and literacy development on an ongoing basis (McKay, 2006). Currently, most of the scholars consider CbA more reliable and valid for assessing YLLs' language learning progress (McKay, 2006; Cameron, 2001; Moon, 2000; Ioannou-Georgiou & Pavlou, 2003).

Classroom-based assessment is referred to as ongoing, informal or continuous assessment that is carried out by teachers in the classroom. Yang (2008) defines CbA as a “small-scale assessment prepared and implemented by teachers in classrooms according to their own teaching objectives and suitable for local students' learning characteristics” (p.89). Since CbA is carried out by teachers, for them, it is a process of listening, observing and gathering evidence to evaluate the learning and developmental status of children in the classroom context (Chen & McNamee, 2007). Hence, CbA seeks to facilitate learners and helps teachers to plan and guide their students according to their developmental needs (Espinosa & Lopez, 2007).

Airasian (1991) argues that CbA “occupies more of a teacher's time and arguably has a greater impact on instruction and pupil learning than … formal measurement procedures” (p.15). In relation to language and literacy, Hamayan (1995) emphasises that CbA can provide powerful evidence of students' literacy development. She further states that CbA can benefit English Language Learners (ELLs) because it “allows for the integration of various dimensions of learning as relating to the development of language proficiency” (p.214). CbA can provide better possibilities to look at multifaceted concepts such as language ability and reading in a contextualised setting (Hamayan, 1995). The assessments present a well incorporated image of students' weaknesses and potential that can direct the teaching process. CbA that is integrated with children's experiences in the classroom where they participate in discussion as well as engage in formal and informal learning experiences can guide instruction. It provides helpful information about young children's language and literacy development. The information gathered must be measured keeping in view the aims of literacy development which should be suitable, yet challenging, for young learners (Shepard, Kagan, & Wurtz, 1998). With reference to reading skills specifically, Mariotti and Homan (2005) assert that reading assessment is about “gathering of information to determine a student's developmental reading progress; it answers the question, "At what level is this student reading?” (p.2). In addition, assessment provides information about students' development in all the components of reading for example, phonemic awareness, fluency and comprehension. Furthermore, Garcia and Pearson (1994) affirm that CbA not only provides insights about the reading strategies employed by the readers in a contextualised setting but also enables a teacher to measure complex reading tasks. Burnett and Myers (2004) stress that while assessing reading skills, it should be kept in mind that reading is ultimately about acquiring meaning from written text; therefore, assessment should help in providing insights about children's ability to read for meaning. While considering the assessment of reading skills as a component of language and literacy assessment – and specifically for reading comprehension assessment – teachers mostly use informal procedures that include checklists, observational notes and rating scales. These assessment strategies provide valuable evidence of students' performance that allow teachers to modify the curriculum in order to meet the distinctive learning needs of each child (Leslie & Caldwell, 2009).

It is important to pay heed to what teachers believe to be significant in terms of assessment as they are the primary stakeholders who are involved in assessing children on a regular basis (Jia, Eslami & Burlbaw 2006). It is argued that teachers' beliefs tend to influence their assessment practices (Assessment Reform Group, 1999) and play a fundamental role in their decision-making about classroom assessment practices (McMillan, 2007). Jia, Eslami and Burlbaw (2006) in their study on ESL (English as a Second Language) teachers' perceptions about classroom-based reading assessment found that teachers' beliefs about CbA played an important role in their decisions about teaching and assessing reading. Teachers used those assessments to guide their instruction. In addition, teachers believed that CbA helped them to facilitate the academic needs of their children.

The study aimed to explore classroom-based assessment strategies to assess the reading skills of young learners. Prior to intervention and as part of this action research it was important to explore a teacher's perception about the reading assessment of young children. In addition, the prevalent practices of assessing reading skills were also explored. Data collection occurred in a private English medium school in Karachi, Pakistan. The school had an early years' section where children from 3 to 8 years studied. Grade II was selected because of the researcher's familiarity with teaching that particular age group.

The study was conducted with one early year's teacher (Amina)1 who had three years' experience of teaching English to young children and four focused group children (two girls and two boys) aged 6-7 years. The consent of different stakeholders (the school management, the teacher and parents) was taken prior to data collection. Children were selected randomly and their permission was sought through an assent letter before the study commenced.

Data were collected through multiple sources which included semi-structured interviews and classroom observations that were followed by informal discussions. Furthermore, documents such as students' progress cards, the teacher's instructional planner, the reading textbook, records maintained by the teacher for children's progress and monthly test papers were reviewed. Lastly, the researcher also maintained a reflective diary throughout the research process to record personal reflections.

Data were analysed on an ongoing basis during the study. All the data were transcribed and analysed. After the data collection phase, the data were revisited and codes and themes developed. Similar themes were categorised into main themes for recoding purposes. For respondent validation, interview transcriptions were read and approved by the participant teacher.

The following two themes emerged from the data: (i) teacher's perception of young children's assessment with respect to reading; and, (ii) existing practices of reading assessment.

Under this theme, Amina's views about the purpose for assessing the reading skills of young children and the use of assessment information are shared.

The purpose of reading assessment according to the teacher was “to make them [children] perfect in reading” (Teacher Interview, February, 6, 2012). Mariotti and Homan (2005) describe reading assessment as gathering information to determine a student's developmental reading progress. However, Amina mainly focused on perfecting students' reading skills, which might be the ultimate objective of assessment in her opinion. Further probing led Amina to elaborate her understanding about the word 'perfect': “perfection comes by the [sic] improvement” (Teacher Interview, February 6, 2012). Her statement highlighted the means of attaining perfection and not exactly what perfection meant to her. The question that arose here was about the meaning of 'perfection': was it when children could read without making mistakes, memorise the text, or understand and make meaning of the text? Amina believed that when assessment results were not according to the requirement or standards set by the teacher then she should make efforts to improve pupils' reading skills which should lead to perfection. It appeared that Amina had some idea about assessment in that it should improve children's learning; however, she was of the view that improvement in reading skills could only be brought about through practice of the same text.

Assessment was closely tied with the instructional objectives set by the teacher; however, in Amina's case the objective of developing and assessing reading skills was unclear. She wanted her children to be perfect in reading but her notion of perfection itself was ambiguous.

For Amina, another purpose of assessment was to polish the areas of the children where they were lacking (Teacher Interview, February, 9, 2012). She further expressed her understanding through an example: “If the child is not able to read the several sounds or blends, I will more concentrate on that part, to make him read that” (Teacher Interview, February, 9, 2012). It appears from the data that she highlighted the deficiencies in children's learning and thought that by working on the weak areas, children would automatically improve their skills, which would eventually lead to perfection in reading skills. Amina seemed to use assessment information to emphasise the instruction or teaching of the weak areas which was one of the purposes of young learners' assessment but not the sole objective of it (Slentz, Early & McKenna, 2008).

Amina elaborated upon how she polished the weak areas of students. If she had given a 'B' grade to a child in reading by looking at his/her class performance or through reading aloud, then she would work with that individual by giving him/her additional comprehension tasks so that the learner could have a better grasp of the concept (Teacher Interview, February, 9, 2012). She used assessment information to enable children to work on their weak areas in order to address those. It is possible that the teacher might not have considered using assessment information for other purposes, such as, improving her teaching practice or providing feedback to the children in order to improve their reading skills. Amina seemed to use assessment exclusively for diagnostic purposes where the areas for improvement were emphasised and students' learning was supported in those particular areas (Slentz, Early & McKenna, 2008).

When asked whether Amina used assessment information to improve her teaching practice or bring a change in her teaching strategy, she stated:

I think that in reading skill, assessment does not work that much. It is not a mathematics skill that if a child is unable to do addition, we teach him the way to add. (Teacher Interview, February, 9, 2012)

The preceding comments indicated Amina's belief that reading skills could not be taught explicitly. According to her, “Reading is improved through practice. Means if there are some flaws in a child's reading then we can practice those flaws enough that the child becomes perfect in that” (Teacher Interview, February, 9, 2012). However, literature on reading development in young learners strongly advocates the intentional teaching of comprehension strategies to enable learners to make sense of the printed material (Duffy 2002 as cited in Ness, 2011; Grabe & Stoller, 2002).

Amina's view about reading skills also influenced her view of assessment (McMillan, 2004). Since she believed that reading was developed through practice she made children practice the weak areas to the point where she believed that learners had gained perfection in those specific areas. This, according to her, was the way in which assessment improved children's reading skills. The question that arose, however, was that if the skills were not taught or introduced explicitly how could children practice them or enhance their skills? If a teacher desired children to practice comprehension then she would have to teach comprehension strategies to children in the first instance. Perhaps Amina thought that reading skills could not be taught to children and hence, to her, there was little that assessment could do to help in improving her teaching. This appeared to be the reason why she did not use assessment information “to tailor appropriate instruction to young children” (National Association for the Education of Young Children [NAEYC], 1998, p.14) which was one of the characteristics of sound assessment.

Under this theme, the teacher's existing assessment practices for assessing the reading skills of young children are explored along with a brief account of the strategies employed by the teacher.

NAEYC (2005) strongly recommends using multiple methods of assessment and data collection to elicit a broader picture of YLLs' early literacy development. Amina reported the use of a variety of assessment strategies to assess the reading skills of students. She said: “I can ask them [children] to read from the reader directly or I can use variation and assess them. It's up to me” (Teacher Interview, February, 9, 2012). During observation, interview and document analysis, it became evident that reading aloud, reading passages and multiple choice questions [MCQs] in the monthly assessment, reference to context and retelling were the strategies used by Amina to assess students' reading. It is also noted that except for monthly assessments, the strategies used by the teacher were of her own choice and the school management did not have any prescribed modes of assessment. The assessment strategies used by Amina are discussed in detail in the following paragraphs.

The following episode describes how a teacher uses read aloud assessment strategy. She asked one child to start reading. The teacher listened to the child reading and also instructed the other children to listen carefully. After three sentences, she asked the boy to sit and asked another child to read from where the last child had stopped reading (Observation, February, 6, 2012). This strategy is called 'Round Robin' or 'Oral Reading' and involved a child reading aloud either to the teacher or to the whole class while the rest of the class listened. This strategy was used to assess “word pronunciation, recognition of punctuation, speed of reading (checked through pace), and understanding of meaning (checked through intonation, stress and voice modulation revealing shades of meaning)” (McKay, 2006, p.234). For Amina the purpose of this assessment strategy was:

When I ask a child to read, all the children have to concentrate on the passage where the child is reading and I used to ask the meaning of these read passages from other child[ren] to assess all [sic] the class is able [sic] to comprehend the text or all are putting their efforts to understand the passage which is read aloud. (Teacher Interview, February, 9, 2012).

The teacher used Read Aloud strategy for other purposes than those that have been established in the literature. Her focus seemed to be on the words read correctly by the children and she also used the strategy to get children to listen carefully because their turn could very well be next. This strategy may be a setback to the non-fluent readers who make mistakes while reading and thus these readers may lose interest in reading (Fair & Combs, 2011). In addition, reading aloud may not tell the teacher how well the children have understood the text because children tend to memorise the text and read it fluently which may misguide the teacher into believing that a child knows how to read but in reality the child has merely memorised the text (McKay, 2006).

Another strategy that Amina applied to assess the reading skills of YLLs was retelling. She asked a child to retell what the previous child had just read. She instructed:

T: So Seema2, can you speak up, what they have read? What are they telling in these lines?

S: The carpet is so fast and Kipper said 'Oh' and Biff said 'I hope we are going to land?'

T: Seema, you are not looking at the words; instead you are telling on your own. Look at the words properly. The teacher asked the child to retell the last few sentences of the story. (Observation, February, 6, 2012)

Amina's focus was on retelling the lines read by the children. She wanted the child to use the same words as those in the text as she asked the child to look at the words carefully and not add his/her own words. It clearly indicated that she focused on reading the text with accuracy. Her objective of using 'retelling' as an assessment strategy was:

Through retelling, their (children's) reading skill is not assessed. In school we used to tell the story of the reader before beginning the reading session to children in story form so [that] any child can retell using the same concept. Therefore, through retelling[,] their speaking skills develop and it is an after reading activity too. (Teacher Interview, February, 9, 2012)

Retelling is considered as one of the reading assessment strategies, which is widely used to assess the comprehension of young children through summarising the events of the story in their own words (Freebody & Austin, 1992; Rathvon, 2004; Mariotti & Homan, 2005). However, it is interesting to note that though Amina mentioned this strategy for reading assessment, she seemed to use retelling just as an after-reading activity and not for assessing children's reading skills. Probably, she used this strategy to check if the children had understood the specific lines or paragraphs and could retell these using the same words. However, this contradicted the literature in terms of the actual purpose of retelling as an assessment strategy.

Amina did not see any harm in focusing on the exact words of the text. She believed that memorisation was important to develop at this stage because it would benefit students later in their academic life where they would have to memorise the content in order to appear in the examination and score higher marks. Moreover, she stressed using the exact words from the reader because she believed “if we emphasise on using the same words from the book then it will help them in developing that (spoken language)” (Teacher Interview, February 9, 2012). It seemed that Amina was unaware about the other modes of developing spoken language and vocabulary of the students; therefore, she gave prominence to using the same words as text.

Another assessment strategy that Amina applied was reference to context. According to her it assessed the 'comprehension' of students. The reader included in the curriculum had dialogue as part of the text. The teacher asked the children different questions such as 'Who said these words and to whom?' She asked:

T: Who has spoken these words? 'I have never seen a town like this?’

Students' choral response: 'Biff'.

T: How come [sic] you know?

S: It is written in the sentence. (Teacher Observation, February, 6, 2012)

According to the teacher, “this helps children in comprehension a lot because if children understand the words spoken by whom in the story then they can comprehend the text easily” (Teacher Interview, February, 6, 2012). According to Amina, the 'reference to context' strategy assessed the comprehension of students as children learnt and knew which dialogue was spoken and by which character. After a closer look, it appeared that this strategy also encouraged memorisation of the text. Children could learn the dialogues without understanding their meaning or connection to the text. Apparently, this strategy was the result of Amina's understanding of reading and comprehension which seemed to be 'learning the text by heart'.

It was found that almost all the assessment strategies used by the teacher focused on 'accurate reading' of the words and the text. She considered how well the child could read to her or retell the story by using exactly the same vocabulary from the book in order to report children's reading progress. This indicated that to a greater extent, importance was given to perfect reading of the text while minimal attention was given by the teacher to comprehension or meaning-making. Though Amina believed that her strategies assessed comprehension, it was not the case in most of the strategies in the light of what literature suggested.

The school had a policy of monthly assessments which were conducted at the end of two months. A reading passage was given to the children, which they had to read in order to answer several questions. In addition, children were sometimes asked to fill in the Multiple Choice Questions [MCQs] or answer the questions about the same reader which they had read over a period of two months. When Amina was asked about MCQs given in the monthly assessment, she shared, “the MCQs are related to the reader which we are reading in the class … you can judge the reading skill of that child” (Teacher Interview, February, 9, 2012). She further shared the objective of these types of tests as:

It is to check their memorising skills and to see if with how much interest they (children) have read the story. (Teacher Interview, February, 9, 2012)

The above anecdote clearly indicates that MCQs from the reader were limited to assessing the memory of children by recalling information (Oosterhof, 2003) about a particular reader and not assessing children's comprehension. Additionally, sometimes reading passages prepared by the teacher or taken from the textbook were also included as monthly assessments (Figure 1). These were unfamiliar to the students and were not covered during the month. While sharing the objective of these reading passages Amina said:

We see that how much [the] child has comprehend[ed] the text and he will comprehend the text when he will be able to read. (Teacher Interview, February, 9, 2012).

This aim of reading passages is aligned with Rathvon (2004) who notes that, “performance on passage comprehension tests is influenced by a variety of language and verbal reasoning skills, including lexical, semantic, and syntactic knowledge and is a common method of assessing comprehension” (p.161).The questions in the reading passage also assessed the literal level of comprehension which assessed the factual information given in the text or the reader.

Figure 1. Reading Passage

Based on the interview and classroom observation data of a teacher, it is evident that Amina focused on the diagnostic aspect of assessment in order to develop children's reading skills. She was interested in identifying the weak areas of pupils' reading and work on those (Slentz, Early & McKenna, 2008). However, all her efforts were concentrated on making children read a specific text which according to her was the development of the skill of reading. She did not care much if her students could read texts other than the specific ones. Her major objective was for students to memorise the specific text.

In addition, the data also revealed that the teacher viewed assessment as 'assessment of learning' which was carried out soon after the lesson to assess how much children could read. She did not consider assessment as a means to identify the gap between children's learning, and then take steps – through teaching and feedback to the child – (Sadler, 1998; Cameron, 2001) to improve and facilitate children's learning (Witte, 2012).

Moreover, the teacher's perceptions about assessment influenced the way she assessed and utilised the assessment in her teaching practices (McMillan, 2007). As she did not perceive assessment to be facilitative in her teaching, Amina did not focus on areas for self improvement which would have enhanced her pedagogical repertoire. In addition, the teacher's beliefs about assessment also influenced her choice of assessment strategies. She perceived assessment as a means to make children perfect; therefore, she chose strategies which would eventually lead to memorisation of the text (e.g. read aloud, reference to context, monthly assessment). These strategies could also be used to assess various other dimensions of children's development of reading skills but as the teacher viewed them with a particular lens she did not make use of those strategies to gauge the other aspects of reading progress of the children.

The preceding discussion leads us to focus on the significance of a teacher's professional development in the area of assessment specifically of young language learners. Lack of expertise and training pose challenges for practitioners to facilitate children's learning through assessment (McKay, 2006). Since the research participant in the study did not have any additional training of assessment, her knowledge and understanding about the assessment of young learners' reading skills was limited. Therefore, teachers need to be trained in the area of assessment either by the school administration or for the administration to make assessment a mandatory component for pre-service teachers.

Based on the findings it is suggested that teachers' professional development sessions, seminars and workshops must include assessment as a compulsory component which highlights the importance and enhances the understanding of teachers about classroom-based assessment and its implications on children's language and literacy development (Brumen & Cagran, 2011). The significance of teacher professional development is critical especially in a foreign language context as research also indicates that foreign language teachers who teach young children are not highly skilled in assessment (McKay, 2006).

This study also indicates the need to revisit the assessment policy of the school context in question. Currently, a summative mode of assessment is in practice; however, a summative mode is insufficient to provide teachers and other stakeholders with a holistic picture of children. Therefore, making classroom-based assessment a part of policy will inform teachers' decisions about children and also complement their summative assessment practices.

Teachers should also engage in reflective practice about their teaching and assessment methods with their colleagues. Such collaborative efforts will help them to reflect on their practices and work towards improvement collectively.

Note: The authors would like to thank the school management, the teacher and the students who participated in this study.