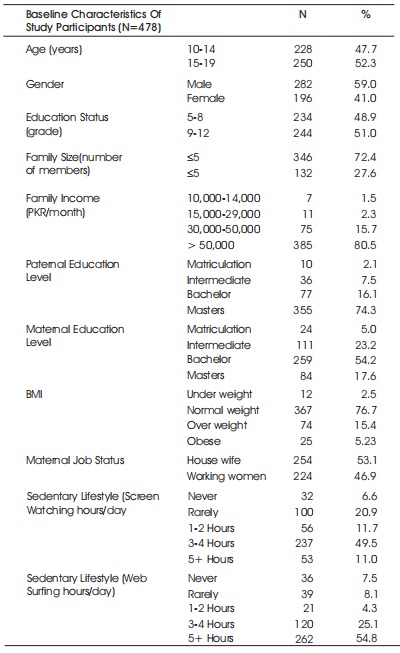

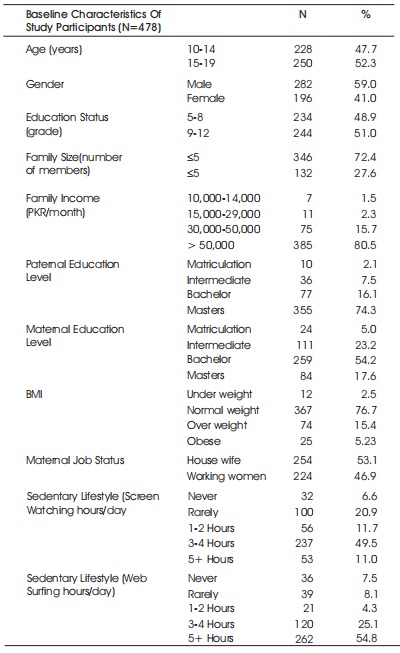

Table 1. Demographic Description of the Study Population

Nutrition transition may have influenced processed food consumption, particularly in middle-income countries like Pakistan. The role of processed foods in nutrition transition has been receiving greater analysis, given that such foods tend to be high in refifined sugars, salt, sodium and fats (saturated and trans). The excessive consumption of these is associated with obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs). To find out the factors contributing towards processed food consumption and frequency of consumption on weekly basis among adolescents of school- going age in Karachi across sectional survey has been conducted in this study, pertaining to six districts of Karachi with a sample size of 478 adolescents. This was done using a multistage simple random sampling technique. A validated ultra- processed food consumption survey questionnaire was adopted. Basic demographics, factors promoting consumption of processed food items and weekly consumption pattern of different items were investigated in school-going adolescents. Of the total, around 92% of a dolescents consumed processed food on weekly basis due to taste (64%) and diversified range of items (41%). Out of these, males (59%) and older adolescents (52.3%) were consuming more processed food. Affordability (98%) and availability (94%) were found as the two main factors for the high consumption of processed food, whereas print and electronic media advertisements (91%), peer pressure (83%) and women employment (59%) were found as the promoting factors for excessive consumption. The consumable items included cold drinks (76%), breads and buns (68%), Banaspati ghee (67%), butter (64%), tetra pack sweetened milks (60%), dawn paratha (44%), jams and marmalades (43%), crisps and snacks (42%), fruit juices (40%), and chocolates (39%). Processed food consumption and its major impact on health are commonly seen in adolescent group. Convenience, affordable prices, peer influences, and heavy marketing of processed and fast food has increased the level of consumption. The study is a preliminary investigation survey providing some evidence on ultra-processed food consumption among school-going adolescents in Karachi. Future research should be done on effective nutrition intervention and promotion strategies to reduce excessive consumption of processed food among the said age group.

Food processing can be termed as any measured change in a food that takes place before it is available for the consumer to eat. It can be as simple as “freezing or drying” by which food preserves its nutrients and freshness, or as compound as formulating a frozen meal with the right balance of nutrients and its other constituents. Ready to eat food can be categorized in two major groups. The first category includes processed food products that are prepared by adding substances to the whole food, causing extensive change in their properties. The second type includes ultra-processed foods which contain little or no whole food and are merely products of industrial ingredients (MacLeish, 2015). According to a cross sectional study in Bahrain, identifying adolescent dietary and lifestyle habits, it was found that about 88% of adolescents snacked during school break, 70.7% procured food from the school canteen, 68.8% preferred regular size burgers, 24.4% preferred large portions of potato chips with very less physical activity. It seemed that the adolescents in Bahrain were moving towards unhealthy dietary habits and lifestyles, which in turn affected their health status (Musaiger et al., 2011). Also among Indian adolescents, dietary behaviors or consumption patterns were so poor, like they consume 70% of unhealthy food and only 30% of fresh fruits, vegetables, grains and legumes, and 47% consumption of 3-4 servings of sugary beverage's (Rathi et al., 2017).

Globally, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) have been recognized as an important public health indicator due to the rapid increase in consumption of processed foods (Monteiro et al., 2010). The role of processed foods in nutrition transition has been receiving greater analysis, given that such foods tend to be high in refined sugars, salt, sodium, and fats (saturated and trans). On a regular basis, consuming a significant amount of processed food may impose harmful effects on human body and can be detrimental to one's health as well. Major health risk factors include diabetes mellitus, obesity or over-weight, hypertension and others. Evidence from past studies have shown that, in USA, diabetes mellitus increased by 29% due to weekly consumption of ultra-processed meats and 47% due to refined carbohydrates. On the other hand, marked increase was seen in individuals suffering from over-weight and obesity in the USA (29%), Southern India (38%), and Sweden (29-39%), due to consumption of processed food and fast food. From various other studies, consumption of processed foods such as patties, samosa, cakes, pastries, muffins, pasta and noodles, fruit juices, chocolates, and frozen Paratha (tortilla), increased the risk of developing overweight (38%), obesity (26%) and diabetes mellitus (26 to 39%) in adolescents from both developed and developing countries (Juul & Hemmingsson, 2015; Joseph et al., 2015; Mendonca et al., 2016). The over consumption of such food has been associated with obesity and diet-related NCDs (Webster et al., 2010). In USA, the prevalence of consumption of ultra-processed foods has been accounted to 57.9%, in Brazil, this prevalence has been recorded as 51.2% of the total caloric intake among adults, (Bielemann et al., 2015; Steele et al., 2016) and in Bahrain, 88% adolescents consumed processed foods (Musaiger et al., 2011). Different studies have shown various factors which influenced to consume ultra processed food which improved the socio-economic status due to dual employment and trade liberalization of ultra-processed food products or urbanization (Hawkes, 2005).

The role of processed foods in nutrition transition in Asia is worth mentioning. Rapid urbanization, industrialization, women participation in economic growth, ease of use and access and time demand are some of the many factors contributing towards this nutrition shift (Popkin, 2006). However, there has been no reported data in Pakistan regarding ready-to-eat processed food consumption. Therefore, from the previous studies conducted in Asia, it became evident that processed food consumption and its major impact on health was commonly seen in adolescent group due to peer pressure influences and heavy marketing of fast food consumption that led to obesity and later diet-related NCDs in adulthood. So, the aim of this study was to find the different factors which contribute towards processed food consumption and the frequency of consumption among adolescents in Karachi, Pakistan.

A cross-sectional survey was done on school going adolescents from all the districts and 18 towns of Karachi from June 2017 to September 2017. Simple Random sampling technique was used to reach the targeted sample size. A sample size was calculated by the WHO sample size calculator using television watching a leading cause for consumption of processed food (47.9%), by keeping margin of error 5% and 95% confidence interval (Barr-Anderson et al., 2009). The estimated sample size was 384. To reduce the missing observation bias, sample size was up sized to 10%; the final sample estimated was 422 and data collection was completed on n=478. The dependent variable was processed food consumption and the independent variables were taste, availability of food in nearby area, peer pressure, women employment and television watching. Inclusion criteria had school going adolescents between 10 to 18years of age while respondents with either physical or mental disability or with any co-morbidity were excluded from the sample. Modified, validated close ended questionnaire with informed consent for data collection was used. The Cornbach's alpha 0.869 confirmed the excellent reliability for the factors contributing consumption through inclusion of all 81 items of the processed food consumption survey questionnaire. The questionnaire has been constructed by modifying the questionnaire used in Canada and Brazil (Moubarac et al., 2014; Louzada et al., 2015). The questionnaire consists of 3 parts which included information regarding socio-demographics, factors associated with consumption of UPF, and frequency of UPF consumption per week. Socio-demographics sections were inquired about their age, family size, family income per month in Pakistani rupees, parental education level, height ( inches), weight ( kilograms) and maternal job status. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated using height (cm) and weight (kg). BMI were reported using WHO categories as 'underweight, normal weight, overweight and obese. Second section inquired about different factors which were associated with consumption of processed food. Frequency of processesfood consumption per week was assessed though a list of 57 frequent food items available in different super markets of Karachi. The list was further divided into 06 groups named as grains, meat, fish and poultry, fats and emulsions, dairy products, fruits and vegetables and additional convenient items. The weekly consumption was recorded as “daily, 4-5 times, 1-3 times, rarely and not at all” for each item. The questionnaire was piloted on 20 respondents; demographic questions were slightly modified according to the context. Informed consent was verbally administered. Data collectors were trained to administer the questionnaire and to maintain the reliability of the research instrument.

For data analysis SPSS version 16.0 was used. Descriptive statistics was performed, where frequency and percentages were reported for categorical variables and mean and standard deviation for continuous variables.

This study is does not any ethical aspect regarding the respondents' autonomy and confidentiality, as there is no personal identification required for the study. The participation was voluntary and respondents were free to withdraw from the survey at any time. While asking the questions, a positive and respectful attitude was shown towards respondents. The permission for conducting the study was granted by Research Review Committee of School of Public Health, Dow University of Health Sciences.

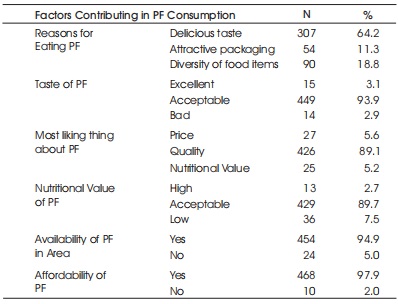

A total of 478 boys and girls were included in this analysis. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of participants who consumed ultra-processed food on weekly basis. Most of the respondents, 72.38% (n=376) had small family size having 5 or less members, and participants were divided into four groups according to their monthly income, majority of the respondents [80.54% (n=385)] had Rs. 50,000 on average as their monthly income. Analysis showed that fathers had highest proportion with masters degree [74.27% (n=355)] whereas mothers’ highest educational attainment was bachelors [54.18% (n=259)] and around 53.14% (n=254) respondents had working mothers. Of the total respondents enrolled in the study, 20.7 %( n=99) were found to be overweight, whereas 2.51% (n=21), 76.77% (n=367) were underweight and normal weight, respectively. Majority of the respondents watched television [49.54% (n=237)] 3-4 hours/day and surfed the internet [54.81% (n=262)] for more than 05 hours/day and respectively. Table 2 shows the various reasons for eating processed food. In our population, processed food is perceived as being less expensive by 97.9% (n=468) and 64.2% (n=307) prefer processed food because of good taste. Quality of the product includes organoleptic properties like texture, aroma, color, flavor and freshness. The most preferred reason for liking processed food was the quality as said by 89.12% (n=426) respondents and 94% participants reported high consumption of processed food because of its availability in their area of residence. Factors promoting consumption of processed food includes; peer pressure, print and electronic media advertisement and women employment. Results showed that the print and electronic media advertisements were the leading factors of processed food consumption among adolescents of Karachi, accounting for 91% (n=436) of the sample. While in contrast to other factors, peer pressure and women employment findings were 83% (n=398) and 59% (n=286) respectively with regard to high consumption. Distributions of the respondents among frequencies of different processed food consumption per week were tabulated in Table 3, which were further divided into six major food groups. Out of 57 processed items majority respondents on daily basis consume 68% breads and buns, and 44% processed ready to eat Paratha, processed meat. Majority of the respondents weekly consumed tetra pack milk and dry powder full cream milk 60.67%, and 50.01% respectively and consume all items in edible oils and emulsions on daily basis along with 38% chocolates, 48% crisp and snacks, 76% soft drinks and colas. Our results show soft drink, bread & buns, and margarine were consumed more by adolescents. 21% of participants were overweight and obese, out of which, the majority consume more conventional items like soft drinks and margarine.

Table 1. Demographic Description of the Study Population

Table 2. Distribution of Respondents among Factors Promoting Processed Food Consumption

To the best of my knowledge, electronic media advertisement and peer pressure to consume such food items were found to be the contributing and promoting factors of processed food consumption among adolescents of Karachi. The various processed food which were found to be consumed by the majority of the adolescents on a daily basis were cold drinks, breads and buns, vanaspati ghee, margarine, tetra pack sweetened milks, ready to eat parathas, jams and marmalades, crisps, fruit drinks, and chocolates. Consumption of processed foods include kofta (meat balls), kabab (meat patties), nuggets, burger patties, broast meats, biscuits and other miscellaneous snacks though consumed slightly less than the above items. The major contributing factors towards processed food consumption were found to be taste of the foods, quality, availability, and affordability in comparison to fresh / home cooked food. The media, peer pressure and employment of women were found to promote more consumption of processed food in our population. Previous study in Sweden revealed that consumption of ultra processed food remarkably increased by 40% from 1960 to 2010 among Swedish adults. Some of the processed foods consumed by the Swedish adults in the study included bread baked products including pizza, cookies and biscuits, processed meat, canned fruits, canned pickle and smoked fish (Juul & Hemmingsson, 2015). Similar findings were also seen in our study with higher consumption of bakery products, processed meat products and frozen meats, and the reason could be a huge/massivemarketingstrategyandmedia advertisement seen recently for the promotion of these food items. Though there is the availability of fresh meat, fish and poultry all across Pakistan, people still consume ultra processed meat in the form of nuggets, croquets, kebabs etc. because these processed items are ready to eat and may save time, and are cost effective rather than preparing and purchasing fresh food items.

Besides the various key contributing factors discussed above, reasons for eating more processed foods were found to be affordability, good taste and quality. Brazilian study had similar finding that the taste of the food and affordability were the major enabling factors for consumption of UPF (Almeida et al., 2018). In our study the majority of the adolescents have been reported to have consumed more processed food despite of the fact that the quality of UPF is dependent on their ingredients which are high in refined carbohydrates and low in micro nutrients. This could be due to promotional marketing strategies which influenced young minds with the help of print and electronic media (Halford et al., 2004; Borzekowski & Robinson, 2001). Furthermore, a survey of food and drinks purchasing habits in Scotland revealed that adolescents were weekly consuming sugary drinks and snacks during lunch time, which is associated with the availability of UPF in nearby supermarkets (Macdiarmid et al., 2015). Because of the availability and affordability of these items in the nearby superstore and schools, accessibility found another contributing factor in this study. In contrast to contributing factors, promoting factors in our study are print and electronic media advertisements, peer pressure and women employment. Even then in majority of the schools’ canteen, packed food items are readily available, especially snacks and fizzy drinks rather than fresh foods. One of the reasons for UPF availability in schools is the comparatively longer expiry dates, by which foods can be preserved for a longer period of time while fresh foods require proper preservation. Moreover, peer pressure and socialization were found more in the adolescents with increased consumption of processed food. In comparison to a cross sectional survey in Netherlands, it was even apparent that adolescents' attitude and peer modeling were directly associated with consumption of snacks and soft drinks during lunch break, and comparable results were found in our study too (van der Horst et al., 2008; Wouters et al., 2010). Adding to this adolescents spend time in watching television, using mobile phone screens and internet surfing more than outdoor games in their leisure time. This duration was found to be significantly high in our study among adolescents. Similarly in Iran, a nationwide study revealed that increased screen time per day of young minds may influence them towards UPF consumption, insomnia and decreased physical activity, which ultimately increased the risk of NCDs (Mozafarian et al., 2017). It has been revealed in our study that adolescents spend more time in front of the screen and because of advertisement and promotion of PFs during that time, they gain impression from media and practice in their life. Moreover, we also found in our study that majority of the adolescents whose mothers were working tend to consume more processed food. In a cross sectional survey in Brazil on UPF consumption among young children, it was found that women employment increases consumption of processed food due to time constraint issues. It further supported our finding that mother's education and child's age were associated with the increase in ready to eat products in their meals (Louzada et al., 2015) The reason could be that mothers were relatively less educated than fathers. Strengths of our study include the concepts of different types of processed food that were clearly defined, and the domains of factors associated with consumption, and consumption of processed food was separately assessed. The cut-off values of body mass index were standardized and can be used for comparison internationally.

This study is the first of its kind in Pakistan providing an evidence-based data on processed food consumption. The limitation of the study is time and budget constraint which restricted the study to be conducted in only 10 towns of Karachi. The sample size is small to generalize the results, however the results are the interpretation of the parameters as consistent with other studies. Parents’ interview could also be included for the advancement in research. Further studies require comparison of promoting and contributing factors among those who did not consume UPF, which also evaluates involvement of socio-economic factors for the betterment of implementation and intervention. Therefore, it is concluded that the findings of different studies conducted in Asia made evident that processed food consumption is commonly seen in adolescent group due to availability, diversified range of different food items, convenience, peer pressure influences and heavy marketing of processed food consumption which leads to obesity and later diet related NCDs like diabetes mellitus, hypertension and others in adulthood. Analysis suggests that more action is needed by policy-makers to prevent or mitigate processed food consumption (Baker & Friel, 2014). There is an urgent need to develop nutritional policies regarding consumption of healthy food and minimizing food wastage to ensure food safety and quality of food products.

This study is a preliminary investigation survey to provide basic information about ultra-processed food consumption among adolescents in Karachi. Due to limited nutrition education in Pakistan, most of the people face difficulty in finding appropriate, good quality, economical and healthy food to eat in their daily meals, and therefore often compromise their health by consuming unhealthy processed food. In Pakistan, health services are more inclined towards curative health care and less focus is given to the preventive measures and public awareness programs. Recently, Pakistan government has introduced some policies in oder to prevent NCDs at an early age.

I would also like to acknowledge Ms. Sumera Inam, Dr. Wardah Ahmed and Mr. Haris Bin Haider, and all other participants who provided me their continuous encouragement, cooperation, unconditional support and suggestions.