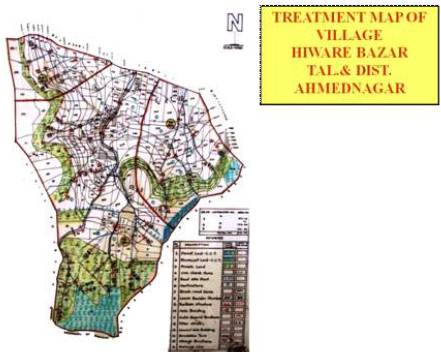

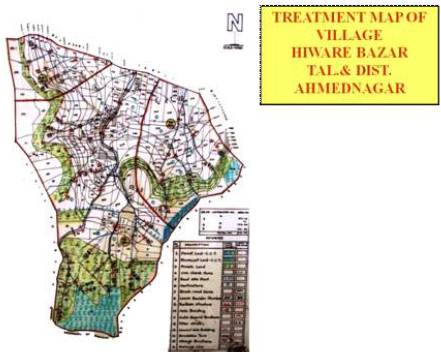

Figure 1. SWC Treatment Map of Village

Watershed is not simply the hydrological unit but also socio-political-ecological entity which plays crucial role in determining food, social, and economical security and provides life support services to rural people. The criteria for selecting watershed size also depend on the objectives of the development and terrain slope. A large watershed can be managed in plain valley areas or where forest or pasture development is the main objective. In hilly areas or where intensive agriculture development is planned, the size of watershed relatively preferred is small. This paper describes the concept, principles and challenges in watershed management.

The rain-fed agriculture contributes 58 percent to world's food basket from 80 per cent agriculture lands (Raju et al. 2008). As a consequence of global population increase, water for food production is becoming an increasingly scarce resource, and the situation is further aggravated by climate change (Molden, 2007). The rain- fed areas are the hotspots of poverty, malnutrition, food insecurity, prone to severe land degradation, water security and poor social and institutional infrastructure (Rockstorm et al. 2007; Wani et al. 2007). Watershed development program is, therefore, considered as an effective tool for addressing many of these problems and recognized as potential engine for agriculture growth and development in fragile and marginal rain-fed areas ( Joshi et al. 2005; Ahluwalia and Wani et al. 2006). The world is rapidly converting forest, wetlands and other critical habitats into agricultural land to meet growing demands and diverting major rivers to produce food (Anonymous, 2005). How to produce more and better food and maintain or improve critical ecosystem services without further undermining our environment is a major challenge. Small holder farmers, livestock keepers, forest users, and others who derive livelihoods from land and water find that their interactions affect others in a watershed context. As a unit of land and water management, the watershed offers immense scope to improve crop productivity whether of rainfed crops or under small-scale irrigation and biomass for livestock. The concept of integrated and participatory watershed development and management has emerged as the cornerstone of rural development in the dry and semi-arid regions and other rain fed regions of the world, and is a paradigm shift from earlier plot-based approaches to soil and water conservation. Management of natural resources at watershed scale produces multiple benefits in terms of increasing food production, improving livelihoods, protecting environment, addressing gender and equity issues along with biodiversity concerns ( Sharma, 2002; Joshi et al. 2005; and Rockstorm et al. 2007).

About 60 percent of total arable land (142 million ha) in India is rain-fed, characterized by low productivity, low income, low employment with high incidence of poverty and a bulk of fragile and marginal land (Joshi et al. 2008). Rainfall pattern in these areas are highly variable both in terms of total amount and its distribution, which lead to moisture stress during critical stages of crop production and makes agriculture production vulnerable to pre and post production risk. Watershed development projects in the country has been sponsored and implemented by Government of India from early 1970s onwards. Various watershed development programs like Drought Prone Area Program (DPAP), Desert Development Program (DDP), River Valley Project (RVP), National Watershed Development Project for Rain-fed Areas (NWDPRA) and Integrated Wasteland Development Program (IWDP) were launched subsequently in various hydro-ecological regions, those were consistently being affected by water stress and draught like situations. Entire watershed development program was primarily focused on structural-driven compartmental approach of soil conservation and rainwater harvesting during 1980s and before. In spite of putting efforts for maintaining soil conservation practices (example, contour bunding, pits excavations etc.), farmers used to plow out these practices from their fields.

The integrated watershed development program with participatory approach was emphasized during mid 1980s and in early 1990s. This approach had focused on raising crop productivity and livelihood improvement in watersheds (Wani et al. 2006) along with soil and water conservation measures. The Government of India appointed a committee in 1994 under the chairmanship of Prof. CH Hanumantha Rao. The committee thoroughly reviewed existing strategies of watershed program and strongly felt a need for moving away from the conventional approach of the government department to the bureaucratic planning without involving local communities (Raju et al. 2008). The new guideline was recommended in year 1995, which emphasized on collective action and community participation, including participation of primary stakeholders through community-based orgnizations, non-governmental organizations and Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRI) (GoI, 1994, 2008; Hanumantha Rao et al. 2000; DOLR, 2003; and GoI, 2008; Joshi et al. 2008). Watershed development guidelines were again revised in the year 2001 (called Hariyali guidelines) to make further simplification and involvement of PRIs more meaningful in planning, implementation and evaluation and community empowerment (Raju et al. 2008) and guidelines were issued in year 2003 (DOLR, 2003). Subsequently, Neeranchal Committee (in year 2005) evaluated the entire government-sponsored, NGO and donor implemented watershed development programs in India and suggested a shift in focus “away from a purely engineering and structural focus to a deeper concern with livelihood issues” (Raju et al. 2008). Major objectives of the watershed management program are: i) conservation, up-gradation and utilization of natural endowments such as land, water, plant, animal and human resources in a harmonious and integrated manner with low-cost, simple, effective and replicable technology; ii) generation of massive employment; iii) reduction of inequalities between irrigated and rain-fed areas and poverty alleviation.

A watershed, also called a drainage basin or catchment area, is defined as an area in which all water flowing into it goes to a common outlet. People and livestock are the integral part of watershed and their activities affect the productive status of watersheds and vice versa. From the hydrological point of view, the different phases of hydrological cycle in a watershed are dependent on the various natural features and human activities. Watershed is not simply the hydrological unit but also socio- political-ecological entity which plays crucial role in determining food, social, and economical security and provides life support services to rural people (Wani et al. 2008).

Hydrologically, watershed is an area from which the runoff flows to a common point on the drainage system. Every stream, tributary, or river has an associated watershed, and small watersheds aggregate together to become larger watersheds. Water travels from headwater to the downward location and meets with similar strength of stream, then it forms one order higher stream. The stream order is a measure of the degree of stream branching within a watershed. Each length of stream is indicated by its order (for example, first-order, second- order, etc.). The start or headwaters of a stream, with no other streams flowing into it, is called the 1rst-order stream. First-order streams flow together to form a second-order stream. Second-order streams flow into a third-order stream and so on. Stream order describes the relative location of the reach in the watershed. Identifying stream order is useful to understand amount of water availability in reach and its quality; and also used as criteria to divide larger watershed into smaller unit. Moreover, criteria for selecting watershed size also depend on the objectives of the development and terrain slope. A large watershed can be managed in plain valley areas or where forest or pasture development is the main objective (Singh, 2000). In hilly areas or where intensive agriculture development is planned, the size of watershed relatively preferred is small.

Entry Point Activity is the first formal project intervention which is undertaken after the transect walk, selection and finalization of the watershed. It is highly recommended to use knowledge-based entry point activity to build the rapport with the community. Direct cash-based EPA must be avoided as such activities give a wrong signal to the community at the beginning for various interventions. Details of the knowledge-based EPA to build rapport with the community ensuring tangible economic benefits to the community members are described here.

Soil and water conservation practices are the primary step of watershed management program. Conservation practices can be divided into two main categories: i) in-situ and ii) ex-situ management. Land and water conservation practices, those made within agricultural fields like construction of contour bunds, graded bunds, field bunds, terraces building, broad bed and furrow practice and other soil-moisture conservation practices, are known as in-situ management. These practices protect land degradation, improve soil health, and increase soil-moisture availability and groundwater recharge. Moreover, construction of check dam, farm pond, gully control structures, pits excavation across the stream channel is known as ex-situ management. Ex-situ watershed management practices reduce peak discharge in order to reclaim gully formation and harvest substantial amount of runoff, which increases groundwater recharge and irrigation potential in watersheds.

The crop diversification refers to bringing about a desirable change in the existing cropping patterns towards a more balanced cropping system to reduce the risk of crop failure; and crop intensification is the increasing cropping intensity and production to meet the ever increasing demand for food in a given landscape. Watershed management puts emphasis on crop diversification and intensification through the use of advanced technologies, especially good variety of seeds, balanced fertilizer application and by providing supplemental irrigation.

Farmers those solely dependent on agriculture, hold high uncertainty and risk of failure due to various extreme events, pest and disease attack, and market shocks. Therefore, integration of agriculture (on-farm) and non-agriculture (off-farm) activities is required at various scales for generating consistent source of income and support for their livelihood. For example, agriculture, livestock production and dairy farming, together can make more resilient and sustainable system compared to adopting agriculture practice alone. Product or by-product of one system could be utilized for other and vice-versa. In this example, biomass production (crop straw) after crop harvesting could be utilized for livestock feeding and manure obtained from livestock could be applied in the field to maintain soil fertility. It includes horticulture plantation, aquaculture, and animal husbandry at indivisible farm, household or community scale.

Watershed development requires multiple interventions that jointly enhance the resource base and livelihoods of the rural people. This requires capacity building of all the stakeholders from farmer to policy makers. Capacity building is a process to strengthen the abilities of people to make effective and efficient use of resources in order to achieve their own goals on a sustained basis (Wani et al. 2008). Unawareness and ignorance of the stakeholders about the objectives, approaches, and activities are the reasons that affect the performance of the watersheds (Joshi et al. 2008). Capacity building program focuses on construction of low cost soil and water conservation methods, production and use of bio-fertilizers and bio-pesticides, income generating activities, livestock based activities, waste land development, market linkage for primary stakeholders. Clear understanding of strategic planning, monitoring and evaluation mechanism and other expertise in field of science and management is essential for government officials and policy makers. The stakeholders should be aware about the importance of various activities, their benefits in terms of economics, social and environmental factors. Therefore, organizing various training at different scales are important for watershed development.

This approach suggest the integration of technologies within the natural boundaries of a drainage area for optimum development of land, water, and plant resources to meet the basic needs of people and animals in a sustainable manner. This approach aims to improve the standard of living of common people by increasing his earning capacity by offering all facilities required for optimum production (Singh, 2000). In order to achieve its objective, integrated watershed management suggests to adopt land and water conservation practices, water harvesting in ponds and recharging of groundwater for increasing water resources potential and stress on crop diversification, use of improved variety of seeds, integrated nutrient management and integrated pest management practices, etc.

Consortium approach emphasizes on collective action and community participation including of primary stakeholders, government and non-government organizations, and other institutions. Watershed management requires multidisciplinary skills and competencies. Easy access and timely advice to farmers are important drivers for the observed impressive impacts in the watershed. These lead to enhance awareness of the farmers and their ability to consult with the right people when problems arise. It requires multidisciplinary proficiency in the fields of engineering, agronomy, forestry, horticulture, animal husbandry, entomology, social science, economics and marketing. It is not always possible to get all the required support and skills-set in one organization. Thus, consortium approach brings together the expertise of different areas to expand the effectiveness of the various watershed initiatives and interventions.

Equitable sharing of the benefits among all the intended population of the watershed remains a major challenge. By their nature, area development programs offer benefits primarily to landowners, with landless people benefitting indirectly, either through peripheral programme activities or trickle-down effects. In fact, watershed projects can actually make women and landless people worse off by restricting their access to resources that contribute to their livelihoods. Even some of the more participatory projects have found it difficult to ensure that benefits reach all the intended population. The very best projects help the poorest and socially backward community members negotiate with other members to ensure that everyone benefits, but this remains an area where all projects need to pay special attention.

Experience has shown that sustainability of watershed management projects is closely linked to effective participation of the communities who derive their living from natural resources. This requires sustained effort to inform and educate the rural community, demonstrate to them the benefits of watershed development and that the project should be planned and implemented locally by the rural community with external expert help (from government and non-governmental agencies) as required. Since the rural societies in the poor and developing countries are plural and stratified, divisions are based on gender, caste and religious groups, and socioeconomic status including land tenure; ensuring participation of all sections becomes a major exercise in patience and social maneuvering. The better performance of the projects with higher-levels of participation seems to be related to the complex, often site-specific locally prevalent livelihood systems. It is important to understand the conditions when people participate in watershed management programmes. These are: (i) making people aware of potential benefits of collective action in conserving and managing natural resources; (ii) including demand driven activities in the watershed program; (iii) empowering people in planning, implementing and managing watershed programs; and (iv) expecting high private economic benefits (Joshi et al. 2008). The major challenge is to benefit the landless, the socially disadvantaged and resource-poor participants who have low ability to pay for the different programmes.

In general, government projects focus largely on technical improvements; the non-governmental organizations focus more on social organization and the collaborative projects try to draw on the strength of both the approaches. Fixed guidebook and physical target-driven approaches pursued by technocratic, hierarchical organizations are poorly suited to sustainable watershed management programmes. Organizations with better social skills (read NGOs) devote time and resources to organize communities to establish locally acceptable social arrangements and community-based leadership for watershed interventions. As such but with some exceptions, the performance of government-managed watersheds has been more modest while those managed by research institutions and reputed NGOs have been rather successful. The technocratic project officials who oversaw top-down approaches for many years are increasingly being called on to increase the level of local participation in the new government projects. Expecting them to rapidly transform their mindset from supervisor to facilitator is unrealistic; it will take time, orientation, training where required, and encouragement. Given the limited number of such organizations in poor and developing countries on the one hand, and the massive need and ambitious plans for watershed development on the other, implementation capacity poses a serious challenge.

Most of the successful watershed programmes in India have been implemented on a small scale in a few villages and through the collaborative and concerted efforts of research institutes, non- governmental organizations and government departments. These projects were successful as the participant organizations devoted time and resources to social organization, built each group's interests in the project, worked with the farmers to design interventions and select technologies; chose the village not the watershed as the unit of implementation; screened villages for enabling conditions, and ensured effective coordination in their work. This facilitated the development of successful model watersheds like Sukhomajri, Ralegaon Sidhi, Chitradurga, Fakot, Kothapally, Tejpura, Alwar (all in India). Such special treatment will not be possible as watershed projects are replicated. Additionally, depending on NGOs to implement projects may work well on a small scale, but there are not enough capable NGOs to do so on the vast scale required to cover millions of hectares in remote and difficult terrain. Certain states in India have been more successful than the others by implementing these projects in “mission mode”, viz., Adarsh Gaon Yojana (Maharashtra), Karnataka Watershed Mission and Rajiv Gandhi Watershed Mission (Madhya Pradesh). Leveraging of international support from large donors like the World Bank, DFID, DANIDA, SIDA etc. have also been quite helpful in developing proper protocols, implementation strategies and internalizing international experience.

Property rights and collective action institutions fundamentally shape the outcomes of resource governance (Knox and Meinzen-Dick, 2001). Most successful watershed development projects create either a surface water body and/ or augment the underground water reservoir. Sharing of the created resource and ensuring its sustainability, especially the groundwater resource, is a complex problem. The famous Sukhomajri watershed is unique where the benefits were distributed equitably to all the villagers including the landless labourers and marginal farmers (Arya and Samra, 2001) and thus everyone had the incentive to save water. While surface water resource can be managed to some extent through conveyance, with groundwater the issue is particularly difficult. First, it is not always the case in small watersheds that water recharged through efforts in a particular village remains available to the same population. Second, water laws in most countries (including India) state explicitly that any landowner is entitled to water pumped from beneath his land, as long as it does not interfere with drinking water supplies (Sharma, 2001). As a result, project organizations can try negotiating arrangements to share groundwater, but they cannot force landowners who dissent.

Watershed programmes are often viewed as a shortcut to rural development; different ministries, organizations and institutions with divergent interests working at different levels have been implementing watershed programmes, giving rise to inherent contradictions and conflicts. Such conflicts may be at the federal level between different ministries (agriculture, rural development, forestry, environment, water resources etc.), each following its own guidelines, interests, approaches and resource allocation protocols. Whereas the agriculture ministry places greater emphasis on food production, the rural development ministry may design programmes for poverty reduction and employment generation, or the forest ministry declares all forest areas within the watershed 'out of bounds' for all other ministries. At the state and district level the conflicts are observed between government bureaucracy and elected representatives. It is important to internalize the comparative strengths of these different organizations in order to complement the overall development process by minimizing conflicts. Similarly, watershed committees and village level elected institutions at the local level, government departments and non-government organizations as the project implementing agencies, and upstream and downstream inhabitants within the village/ watershed have different perceptions and expectations from the project that can become potential source of conflict. The challenge is to ensure universal but flexible guidelines at higher levels of governance and the necessary flexibility and adaptability at the grassroots level to manage inherent contradictions and conflicts through adequately designed resolution mechanisms.

Inadequate monitoring and impact assessment of watershed programmes is a major concern. To date there are few comprehensive evaluation studies of integrated watershed management (Kerr, 1996). Watershed development projects affect social, economic and environmental activities. Traditionally, completion of activities and physical and financial targets are monitored rather than the process mapping, results achieved or their biophysical, socio-economic, and environmental impacts (Sikka, 2002).

Researchers and other agencies find it hard to conduct meaningful impact assessment studies mainly for the need of baseline data against which is to compare current conditions, and for lack of monitoring data for easy assessment of current conditions. In both government and non-government implemented projects, typically there is no systematic mechanism for storing baseline data and making it available at a later date. Moreover, these data collected for the purpose of planning (and not evaluation) are often discarded once the project work comes to a close. All publicly funded projects keep detailed records of funds spent, structures built, and other physical targets, but such information does not reveal much about the impacts. Kerr (2002) identified three main constraints for conducting meaningful impact assessments: (i) it is difficult to obtain the data that have been collected for monitoring, (ii) the available data are not organized in a common format across different types of projects, so that are not necessarily useful for comparison between project types; and (iii) the monitoring procedures, even if available in some projects, fail to address socio-economic issues or the implementation process.

There is a strong need to develop common guidelines for collecting baseline and monitoring data, which would not only help in analyzing the impacts of current and future activities but also plan corrective measures after mid-term evaluation.

Knowledge generation for successful design and implementation of large watershed development projects still is mainly entrenched in classical soil and water conservation techniques and makes little use of modern tools and techniques, viz., remote sensing, geographical information systems, decision support tools, computer based planning tools, institutional analysis, poverty and socio-economic analysis etc. There are only a few centres of advanced learning that are engaged in the development and effective dissemination of such knowledge. Government and nongovernment partners in a programme or implementing different projects in the programme should be encouraged to share their knowledge and experiences so as to draw valuable lessons and better appreciate each other's strengths and concerns.

Issues of sustainability, equity, gender and community organization, project management and information system, and monitoring and impact assessment have received little attention in knowledge generation and sharing exercises. The ongoing experience of the International Water Management Institute, in collaboration with the Indian Council of Agricultural Research and the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, to broker knowledge between the Indian National Agricultural Research System and their counterparts in eastern and central African countries has been quite encouraging. ICRISAT is also helping several countries in Southeast Asia and China for developing successful linkages with Indian counterparts on watershed development programmes. For reaching remote areas and a wide variety of knowledge users, setting up of virtual knowledge academies, distance learning programmes and other interactive modes of learning can be very quick, far-reaching and cost effective.

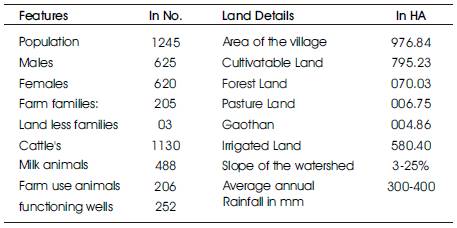

The village Hiware Bazar is situated in Ahamadnagar district of Maharashtra state. It is 45 km away from Pune – Ahamadnagar Highway. South region of Ahmednagar District is having a rainfed farming situation, limited seasonal agriculture, farmers migrate for work. The Area is also frequently suffer to draughts, drinking water scarcity, fodder unavailability, frequent migration to urban areas for employment. The village Hiware Bazar Representative village of this rain shadow areas. The features of the village is shown in Table 1

Problems and Issues of Hiware Bazar before Development: i) Rain fed area (average rainfall 350-400 mm), ii)Rainfed cropping pattern, iii)Heavy soil erosion, iv) Drinking water scarcity, v) Fodder unavailability, vi) Fuel wood unavailability, vii) Social problems, viii) Unemployment, ix) Migration, frustration of villagers, x) Increase in crime, xii) Overall bad reputation of village due to crime.

Adarsh Gram Yojana: The State Government for its Golden Jubilee of State formation announced the “Adarsh Gram Yojana” Hiware Bazar decided to participate in the scheme which aims to: Provide drinking water, Employment, Green fodder, Education and health, Developing the self sustainable village by watershed development, Arresting the migration of villagers towards cities. The Programme implementation was based on following “Panchasutri” (PANCHA SUTRI FOR SUSTAINABILITY): i) Shramdan (Free Labour), ii) Ban on Grazing(Charaibandi), iii) Ban on Tree cutting (Kurhad Bandi), iv) Ban on Liquor (Nasha Bandi), v) Family Planning (Kutumb Niyojan).

Gram Sabha: A Key Factor for Sustainable Village Development: The Hiware Bazar village Gramsabha on its meeting on 15th August 1994 took their decisions and established the “Yashwant Krishi Gram & Watershed Development Trust” for implementing watershed development programme in the village and started implementing the programmes and activities of Adarsh Gram Yojana. Total ban on: i) Bore wells for irrigation purpose (only for drinking water), ii) Water intensive crop cultivation (banana & sugarcane), iii) Selling of land to outsiders, iv) Feeling of ownership village natural resources.

Figure 1. SWC Treatment Map of Village

Table 1. Salient Features of the Village Hiware Bazar

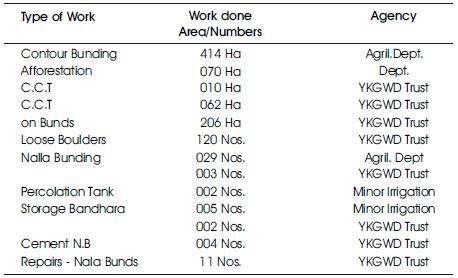

The village Hiware Bazar completed SWC work under Yashwant Krishi Gram & Watershed Development Trust and also by Agriculture Deprtment of Maharashra state is tabulated in Table 2. A huge amount of Plantation is also done. This work gives the strong impacts on village living beings and their environment as follows-

Table 2. Types of SWC Work in Hiware Bazar Village