Table 1. Response Rate from the Five Research Institutes

The study investigates the knowledge management resources and techniques used to enhance knowledge management initiatives in Nigerian agricultural research institutes. The study adopted quantitative approach through questionnaire to collect data randomly from the sample of two hundred and seventy six (N=276) research scientists. The study revealed that cross-functional project teams and mentoring were the main knowledge management resources and techniques used to derive research and innovations in the institutes. Findings also show that the knowledge management initiatives adopted in the institutes include, identification of existing knowledge, improving documentation of existing knowledge, changing of the organisational culture, improving cooperation and communication, externalisation, i.e. tacit to explicit, improving knowledge retention, and improving innovations management. The study concludes that the knowledge management resources and techniques used are capable of enhancing the various knowledge management initiatives adopted in the institutes.

Knowledge Management (KM) involves the processes which produce or discover knowledge and manage the use and distribution of knowledge inside and among organisations. Darroch (2003) states that knowledge consists of three components: acquisition, dissemination, and use or responsiveness. These components of KM are dependent on each other. The effectiveness of the three components in KM requires learning to have taken place to enable individuals to acquire, disseminate, and use knowledge. The knowledge management processes involve a learning aspect. The process facilitates exchange and sharing, and institutionalising of learning that is ongoing inside the organisation (Call, 2005). Nevis, DiBella, and Gould (1997) divide knowledge processing activities into three steps, namely knowledge acquisition, knowledge sharing, and knowledge utilisation, which are key factors in a successful organisation. Instead of knowledge acquisition alone, the term knowledge accumulation will be used throughout the article, as it is a more comprehensive concept than knowledge acquisition alone. In line with the main thrust of the present study, Ruggles (1998) proposed eight major categories of knowledge-focused activities for organisations which would serve as the epitome of knowledge production and management activities. These include:

Successful knowledge strategies in the 21st century depend on whether or not organisations can link their business strategies to their knowledge requirements. This articulation is vital for allocating resources and capabilities for explaining and leveraging knowledge (Madalina, 2012). Ajaikaiye and Olusola (2003) observed that the knowledge system of any progressive society performs a pivotal function in its development. However, they note that “in spite of this recognition, the attention given to Nigeria's knowledge system has been weak and unstable, and has therefore affected its effectiveness and utilization”. The challenge for institutions and countries is thus to determine and develop organisational practices, principles, guidelines, and approaches on how knowledge can be created, harnessed, shared, tracked, and distributed among government agencies, research communities, and the public (Riley, 1998).

According to Jasimuddin (2008), the proliferation of KM field has coincided with the development of the global knowledge-based economy, in which priority has been shifted from traditional factors of production, namely capital, land and labour, to knowledge. In contrast, Drucker (1992) suggests that classical factors are becoming secondary to knowledge as the primary resource for the economy. Several researchers (Davenport & Bibby, 1999) pointed out that the effective management of knowledge is becoming a critical ingredient for organisations seeking to ensure sustainable strategic competitive advantages. Davenport and Bibby (1999) for example, stressed that in the knowledge-based economy competitiveness is increasingly based upon access to knowledge in the form of skills and capabilities. In this knowledge economy, the number of knowledge-based and knowledge-enabling organisations that consider intellectual capital as a prime source is increasing. This increasing awareness of the value of knowledge embedded in experiences, skills, and abilities of people has become an emerging discourse known as knowledge management (Todd, 1999).

The success of organisations (such as agricultural research institutes) in the post-industrial world seemingly lies more in their intellectual abilities than in their physical assets. This requires the transformation of personal knowledge into institutional knowledge that can be widely shared throughout the institution and appropriately applied (Bryans & Smith, 2000). In an empirical study, Bickelmaier and Ringel (2010) investigated KM approaches and strategies from two different angles. First, they presented case studies of the United Nations Development Program, the UN Economic Commission for Asia and the Pacific, the World Bank, the International Atomic Energy Agency, the OECD, and the European Commission. Second, they evaluated the progress of the respective approaches by using common test criteria for KM implementation established in the literature. It was found that all the institutions covered in this contribution have passed the stage of information management and have put active knowledge management systems in place. However, a structured and systematic management of implicit and external knowledge can be found, to a lesser extent. It was established that KM strategies like advocacy and learning, institutionalising KM have been put in place in the organisations.

The knowledge economy is driven by knowledge capital. As today's economy becomes more knowledge and information driven, so does the necessity for effective information and knowledge management strategies in all organisations. KM brings together three core organisational resources-people, processes, and technologies-to enable the organisation to use and share information (Milton, 2003). KM, if properly implemented, and made an integral part of an organisation, can help in saving valuable time wasted in seeking information needed to address socio-economic and development problems (Alvesson & Kärreman, 2001).

During the 1950s, 1960s, and early 1970s, agriculture was the mainstay of the Nigerian economy and contributed over 94% of government revenue and 60-70% of total exports (Daramola, Ehui, Ukeje, & McIntire, 2007). Since the discovery of Nigerian oil in the 1970s, agriculture's significance has declined and oil now totals 95% of exports and 40% of government revenues (Beta, 2012). At present, agriculture only accounts for 0.2% of exports. Declining agricultural production arising from total dependence on crude oil exports as a means of growing the economy has relegated the role played by the agricultural research institutes in innovation development and knowledge discovery, which is now characterised by a myriad of problems, such as poor knowledge management infrastructure, capacity building (i.e. requisite skills and expertise), declining research culture, poor staff motivation, inadequate government support, and a perennially declining research budget.

According to Shehu (2013), Nigeria spends 16.7% of GDP (N1.3 trillion) on food imports. This trend is not sustainable. Nigeria must become self-sufficient in feeding its own people by investing in the agricultural sector. The agricultural research institutes in this regard are vital to drive research and innovation in agriculture. KM is a critical tool in innovation, research, and development.

The main objective of the study was to investigate the knowledge management resources and techniques used to enhance knowledge management initiatives in Nigerian agricultural research institutes. The main objective was further sub-divided in to specific objectives as follows:

In the present study, a quantitative approach through survey design was used to elicit data for the study. The reason for using survey design was to allow for the collection of empirical data from the sample drawn in the five research institutes, using questionnaires and to analyse the data statistically to describe the strategies of knowledge sharing in the institutes. Survey studies describe trends in the data rather than offering rigorous explanations (Creswell, 2002). Survey design has been used in similar studies by (Dawoe, Quashie-Sam, Isaac, & Oppong, 2012; Munyua & Stilwell, 2013).

Out of the 17 agricultural research institutes in Nigeria, five were purposively chosen from the five geo-political zones. Each of the five zones has one major agro-based research institute (ARCN, 2008). The five institutes covered serve as zonal agricultural research coordinating institutes for all the states within the zones, while National Root Crops Research Institute (NRCRI), Umudike serves both South- East and South-South geo-political zones of Nigeria. The research institutes include (ARCN , 2008):

The population of this study is 1363. According to Israel (2013), if the population is 1363 at ±5% precision, the sample should be 276 at the 95% confidence level. The sample of each institute was calculated proportionately. Finally, the data collected from the survey (questionnaire) was sorted, scrutinised, edited to get rid of issues, such as data redundancy, overlap, contextual, and conceptual operationalization and analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 for Windows 7, to generate descriptive statistics via percentages, frequencies, and Pie charts to complement the descriptive statistics and results that were obtained.

This section deals with the analysis of data collected on the strategies for dissemination of knowledge in the five research institutes for increased productivity and diffusion of know-how.

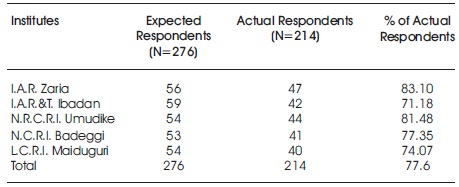

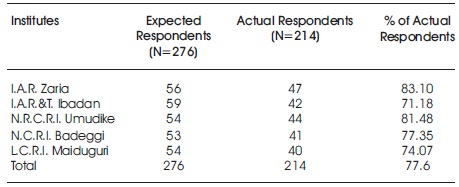

This section presents the total number of returns vis-à-vis the total number of questionnaires administered to the population of researchers in the five research institutes, as depicted in Table 1.

Table 1. Response Rate from the Five Research Institutes

The results in Table 1 show that 214 (77.6%) questionnaires were completed and returned out of the total 276 that were administered. In this regard, 47 (83.10%) were returned from I.A.R Zaria, 42 (71.18%) from I.A.R. & T. Ibadan, 44 (81.48%) from N.R.C.R.I. Umudike, 41 (77.35%) from N.C.R.I. Badeggi, and 40 (74.07%) from L.C.R.I. Maiduguri. From these results, it is evident the highest returns were recorded at I.A.R. Zaria, with 83.10%, followed by N.R.C.R.I. Umudike, with 81.48%.

Demographic analysis was conducted to determine the department/unit/programme, educational status, gender, age, years of working experience, and position/rank of the respondents in the research institutes.

The study revealed that the majority of the respondents were males 151 (70.6%), while females stood at 57 (26.6%), working in various departments/units/ programmes of the institutes, as follows: 18 (8.4%) were working in the Agric Econs and Extension Programme, 29 (13.6%) in the farming system, while 26 (12.1%) were working in the Biotechnology Department. The findings further revealed that 38 (17.8%) of the respondents were working in the product development programme and 24 (11.2%) were in the research outreach departments of the institutes, while the majority 79 (36.9%) of the respondents were working in other departments/ programmes, which include the cassava programme, yam programme, sweet potato, cocoyam, ginger, postharvest, technology, maize, banana, kenaf and jute, cereals, trypanotolerant livestock, grain legumes, land and water resource management, cowpea, groundnut, cotton, confectioneries, castor, and tomato programmes.

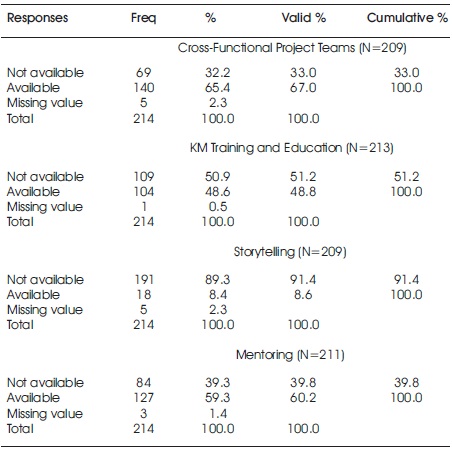

The respondents were asked to identify the KM resources and techniques commonly used in their institutes to derive research and innovation. The results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Knowledge Management Resources and Techniques Available

Table 2 shows the KM resources and techniques used as KM strategies by organisations to enhance productivity and output. The responses were as follows: cross-functional project teams 69 (32.2%) not available, 140 (65.4%) available, and 5 (2.3%) did not respond; KM training and education 109 (50.9%) claimed not available, 104 (48.6%) said it was available, and 1 (0.5%) abstained from commenting; storytelling 191 (89.3%) said not available, 18 (8.4%) said it was available, while 5 (2.3%) did not comment; mentoring 84 (39.3%) not available, 127 (59.3) claimed mentoring was available, and 3 (1.4%) abstained.

Generally, the results show that cross-functional project teams and mentoring were available in the institutes, while storytelling and KM training and education were not available. Coyte, Ricceri, and Guthrie (2012) examined processes used to control the management of knowledge resources in Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in the economic sector of Australia. Their findings revealed that informal, intensive dialogue, and management philosophy, governed by strategy and the management of knowledge resources were the underlying functional KM initiatives and strategies for the enterprises. An important discovery was the culture of teamwork across all employees and the open communication and accessibility to senior managers. Alberts (2007) in a meta-analysis of case studies to determine the individual and team performance in the context of creating organisational knowledge, found that the works of cross-functional teams revolves around coordinating efforts, brainstorming, resolving conflicts and capturing and codifying organisational knowledge; member support; communicating with external stakeholders (e.g. sharing or transferring knowledge to the organisation's management, suppliers and customers); intellectual stimulation, introducing new ideas, recognition of achievements; friendly competition for increased motivation; developing new products; reengineering processes; improving customer relations; and improving organisational performance through critical debates on various solutions.

The researcher wanted to know the KM initiatives adopted by the research institutes for proper management of knowledge. The results are shown in Table 3.

The distribution of KM initiatives available (Table 3) in the institutes show that respondents who noted identification of existing knowledge was not available were 190 (88.8%), while 16 (7.5%) claimed it was available; improved documentation of existing knowledge 203 (94.9%) available, and 5 (2.3%) opined not available; changing of the organisational culture 117 (54.7%) was available, 83 (38.8%) not available; improved co-operation and communication 186 (86.9%) of the respondents claimed was available, while 17 (7.9%) described as not available; externalisation 136 (63.6%) available, while 59 (27.6%) had claimed not available; improving training, education and networking of newly recruited employees 193 (90.2%) were of the view that it was available, while 14 (6.5%) answered not available; improving training and education of all employees 183 (85.5%) said not available, and 27 (12.6%) of the respondents believed it was not available; improving retention of knowledge 175 (81.8%) opined was available, while 20 (9.3%) said not available; improving access to existing sources of knowledge 197 (92.1%) believed was available, and 8 (3.7%) said was not available; improving acquisition or purchasing of external knowledge 143 (66.8%) available, while 57 (26.6%) not available; improving distribution of knowledge 184 (86.0%) of the respondents believed was available, and 25 (11.7%) said it was not available; improving management of innovations 178 (83.2%) available, 30 (14.0%) not available; reduction of costs 110 (51.4%) claimed was available, while 84 (39.3%) believed it was not available.

The findings generally suggest that all the KM initiatives were available in the five agricultural research institutes. In this context, Mishra and Bhaskar (2011) in a study carried out on KM strategies in two information technology (IT) organisations in India, known as Net Centre and Web Centre, established four themes of KM strategies that included knowledge creation, knowledge sharing, knowledge up-gradation, and knowledge retention. On knowledge creation, the findings showed that in Net Centre, knowledge centre happened mostly through both formal and informal ways. However, in Web Centre, knowledge creation took place in a formal and structured manner. In addition, in Net Centre, people were rewarded for idea generation. With regard to knowledge sharing, the commonality between Net Centre and Web Centre lay in their systematic organisational processes, such as meetings, issue chatting, and videoconferencing. Kim, Yu, and Lee (2003) studied on an integrative methodology for planning KM initiatives using literature reviews found that emphasis was placed on improving organisational per formance by identifying and leveraging knowledge directly related to business processes and performance. The findings of Kim et al. (2003) are at variance with the findings of the current study a fact that may be explained by the fact that while the present study was empirical in design, that of Kim was largely based on literature review.

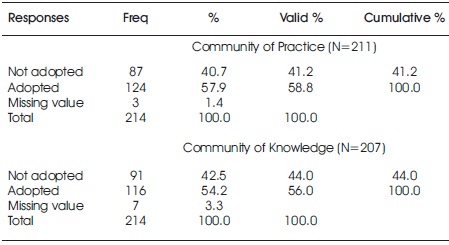

The respondents were asked to indicate the knowledge management best practices adopted in their institutes for efficient knowledge management. The findings are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Knowledge Management Best Practice Adopted in the Institutes

Table 4 shows the responses regarding the knowledge management best practices adopted in the five institutes. The respondents who noted that community of practice was not adopted numbered 87 (40.7%), while 124 (57.9%) said it was adopted, 3 (1.4%) did not respond; community of knowledge 91 (42.5%) not adopted, 116 (54.2) adopted, and 7 (3.3%) abstained from giving a response. It can be surmised that both two knowledge management best practices had been adopted in the research institutes.

As today's economy becomes more knowledge and information driven, so does the necessity for effective information and knowledge management strategies in all organisations. The study investigates the knowledge management resources and techniques used to enhance knowledge management initiatives in Nigerian agricultural research institutes. The study found that cross-functional project teams and mentoring were the main knowledge management resources and techniques used to derive research and innovations in the institutes. This means that there was an investment in community of knowledge practice, cross-functional project teams and mentoring, though to a lesser extent. Findings also show that the knowledge management initiatives adopted in the institutes include, identification of existing knowledge, improving documentation of existing knowledge, changing of the organisational culture, improving cooperation and communication, externalisation, i.e. tacit to explicit, improving knowledge retention, and improving innovations management. The study concludes that the knowledge management resources and techniques used are capable of enhancing the various knowledge management initiatives adopted in the institutes. The study recommends that;