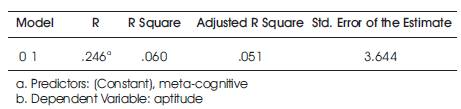

Table 1. Model Summaryc

The present study investigated the relationship between Iranian EFL learners' beliefs about language learning and language learning strategy use. A sample of 104 B.A and M.A Iranian EFL learners majoring in English participated in this study. Three instruments, the Michigan Test of English Language Proficiency (MTELP), Beliefs about Language Learning Inventory (BALLI), and the Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL) were used for data collection. Multiple Regression analysis showed that meta-cognitive strategies were significant predictors of "foreign language aptitude", "nature of foreign language learning", "learning and communication strategies", and "motivation and expectation". Affective strategies also turned out to be predictors of "the nature of foreign language". Another finding was that cognitive strategies were negative predictors of "learning and communication strategies". The findings of the present study may have significant, theoretical and pedagogical implications for learners and teachers.

In recent years, the focus of EFL teaching has shifted from teachers and teaching to learners and learning. In fact, learners play an important role in the process of language learning and are considered as active participants in the learning experience. So, understanding learners' beliefs about language learning is important, because it helps us to understand not only learners' approaches, but also their satisfaction with language instruction (Horwits, 1987, 1988). In addition, beliefs about language learning are found to be closely related to the learners' choice of learning strategies (Yang, 1999). It has been suggested by many researchers that the way learners use learning strategies and learn a second language is under the effect of learners' preconceived beliefs about language learning (Horwitz, 1987, 1988; Wenden, 1986a, 1987a). The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between EFL students' beliefs about language learning and language learning strategy use. Its main concern is to find answers to the following questions:

1. Which of the language learning strategies is a better predictor of foreign language aptitude?

2. Which of the language learning strategies is a better predictor of difficulty of language learning?

3. Which of the language learning strategies is a better predictor of nature of language learning?

4. Which of the language learning strategies is a better predictor of communication?

5. Which of the language learning strategies is a better predictor of motivation and expectation?

Since late 1970s, with the emergence of cognitive revolution, language learners have received increasing attention. Since then, language learning strategies have been at the center of great attention, because focus is shifted from teachers and teaching to learners and learning. Oxford (1990), defines language learning strategies as "specific actions taken by language learners to make learning easier, faster, more enjoyable, more selfdirected, more effective and more transferable to new situations"(p.8).

Moreover, since learners are different, they choose different strategies depending on their understanding of which strategies can possibly facilitate their learning (Cotterall, 2000). In addition, according to Oxford (1992), it is must for teachers to be aware of variables, such as gender, age, motivation, self-confidence, anxiety, language learning styles and strategies and many other factors which are different in various learners. So, awareness of these variables is necessary for teachers to teach successfully.

A number of studies have been conducted to identify what good learners do, to learn a second or foreign language. For instance, Rubin (1971) conducted an investigation into the strategies of successful language learners. She recommends that less successful learners use such strategies. However, Oxford and Ehrman (1995), in their investigation, concluded that successful language learners did not use a single strategy. In other words, successful language learners used a combination of different strategies compatible with their own learning style and task requirements.

In a parallel manner, not all kinds of language learning strategies are of use to all second language learners. It is very important for researchers to discover, what kind of language learning strategies are used by effective language learners. In fact, successful language learners have the ability to use appropriate strategies for the learning task (Vann & Abraham, 1990).

Many researchers have made effort to examine how learner-specific variables such as age, gender, language proficiency, motivation, anxiety, aptitude, cultural background, beliefs about language learning, self-rated language proficiency, and learning styles can influence the use of language learning strategies (Chamot & El- Dinary, 1999; Green & Oxford, 1995; Erman & Oxford, 1989; Oxford & Burry-Stock, 1995; Oxford & Nyikos, 1989; Politzer, 1983). ). The purpose of these investigations was to assist teachers to develop a better understanding of learner differences in language learning.

Oxford, Park-Oh, Ito and Sumrall (1993), in their investigation of the differences in strategy use of males and females found that females use more strategies than males. In the same vein, Green and Oxford (1995) in their study on learning strategies, L2 proficiency, and gender found that females are frequent users of strategies. Also, Sheroy's (1999) investigation on Indian college students showed that, in comparison with male learners, female learners had more frequent use of strategies.

Moreover, Yang (2007) found that both language proficiency and ethnicity affected the students' use as well as selection of language learning strategies. The results indicated that students used memory strategies the least and compensation strategies the most, regardless of ethnic background. Meta-cognitive strategies and memory strategies were found to be used the most and the least, respectively. Furthermore, cognitive, metacognitive and affective strategies were used more by students with a high proficiency level in comparison with those with a low level of proficiency.

Ehrman and Oxford (1989), in their study of the relationship between personality type and strategy use, found that those with an extroverted personality type, in comparison with introverts, were more likely to use affective and visualization strategies, while introverts used strategies for searching for and communicating strategies more frequently than extroverts. In the same study, the researchers found that intuitive type people who are interested in patterns, abstractions, and possibilities, compared with sensing type people who are presentoriented and interested in facts used more strategies for searching for and communicating meaning, building mental models of language, using the language for authentic communication, and managing emotions. This study showed that judging type people (those who need organization and closure), compared with perceiving type people (those who want freedom and dislike closure), more frequently use general study strategies, but perceivers compared with judgers used more strategies for searching for and communicating meaning.

The learning style of language learners plays an important role in language learning strategy choice. Chamot (2004) and Ehrman and Oxford (1989), conducted a study in this area and showed that the type of learning strategies that are used by learners is affected by their own learning style preferences. Also, Sheikhi (2012) studied the relationship between learning style, language learning strategies, and field of study of Iranian EFL learners. 75 undergraduate students were divided into three groups according to their majors; history, physical education, and TEFL. The result showed a significant relationship between students' learning style, language learning strategies and field of study.

In the past two decades, the concept of beliefs about language learning, which belong to the domain of affective variables, has been one of the important variables in language learning process. According to Horwitz (1987, 1988), one of the pioneers in this area, beliefs about language learning refer to language learners' ideas or notions, which have been determined in advance on a variety of issues related to second or foreign language learning. The terms 'opinion' and 'ideas' or 'views' are used by Kunt (1997) and Wang (1996) to refer to 'beliefs'.

Nyikos and Oxford (1993), as an example, have long recognized that a complex group of attitudes, experiences, expectations, and learning strategies are taken into language learning by learners; beliefs are among these variables. Horwitz (2007) considers, control beliefs as central constructs in every discipline, which deal with human behavior. In fact, second and foreign language learners come to class with their specific ideas, about the nature and process of learning. According to Rad (2010) and Dörnyei (2005), learners' beliefs and points of view influence their attempt to learn English and their methods. Horwitz (1999) believes that, it is essential to understand learners' belief about language learning for better understanding of learner strategies and planning appropriate learning instruction. It has been argued by many researchers that there are some beliefs which are beneficial to learners, while others believe that certain beliefs can have negative effects on language learning. Mori (1999), for example, claims that learners' positive beliefs can make for their limited abilities. According to Horwits (1987), some misconceptions and wrong beliefs can have damaging effects on learners' success in language learning.

Several researchers (Horwitz, 1987, 1988; Wenden, 1986a, 1987a) have reported connections between learners' meta-cognitive knowledge or beliefs about language learning and their choice of language learning strategies. Wenden (1987a) found that in many cases, students were able to distinctly describe their beliefs about language learning and also adopt consistent learning strategies. Wenden (1986a) reported that these learners' explicit beliefs about the best way to learn a language seemed to show their choice of learning strategies. Horwitz (1988), based on her survey of University foreign language students, argues that some preconceived beliefs can restrict learners' range of strategy use.

Yang (1999) studied the relationship between learning strategies and beliefs about language learning of 505 Chinese EFL University students in Taiwan. Using Horwitz's (1987) BALLI and Oxford's (1990) SILL and factor analysis, he found that there is a strong relationship between language learners' self-efficacy beliefs and their use of all types of strategies. Also, there was a relationship between their beliefs about the nature of learning spoken English and the use of formal oral practice strategies.

Similarly, Kim (2001) examined 60 Korean University students to investigate the relationship between their use of learning strategies and language learning beliefs. BALLI and SILL were given to the students in order to check their beliefs and use of language learning strategies. They found a strong relationship between the students' use of learning strategies and language learning beliefs. Korean students' beliefs about motivation, self-efficacy, and functional practice led to more frequent use of strategies.

In another study, Sioson (2011) investigated the relationship between learners' beliefs and their strategy use among 300 first year college students in the Philippines. BALLI and SILL were used in this study to collect information on language learners' beliefs and their learning strategies. A negative correlation between language learning strategies and language learning beliefs was reported as the result of the study.

As the above review shows, different studies have come up with different, sometimes contradictory, findings. To resolve part of this controversy, the present study aims to investigate the relationship between Iranian EFL learners' beliefs about language learning and their strategy use.

The participants of the present study initially included a sample of 120 B.A and M.A Iranian EFL students majoring in Teaching English as a Foreign Language and English Translation (both males and females) at Islamic Azad University, Takestan Branch; Imam Khomeini International University; and Kar University in Qazvin, Iran. The Michigan Test of English Language Proficiency (MTELP) was administered to homogenize the participants in terms of their English language proficiency level. As a result, the number of participants was reduced to 104. 14 participants were excluded from the study because they had a different level of proficiency. 6 other participants were excluded because they did not complete the questionnaires.

The following instruments were used to gather data:

1) Michigan Test of English Language Proficiency: The test is a three-part, multiple choice test. It measures learners' grammar, vocabular y, and reading comprehension. This test, which is a reliable one, consists of 40 items on grammar in conversational format, 40 items on vocabulary asking for synonyms or sentence completion, and 20 items on reading comprehension. This test was used to homogenize the participants in terms of their level of English language proficiency.

2) Oxford's (1990) Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL, ESL/EFL 0.7 version): It is a six-part 5-point Likert scale self-report questionnaire consisting of 50 strategy items (from "never" to "always"). The questionnaire contains memory strategies (9 items), cognitive strategies (14 items), compensation strategies (6 items), meta-cognitive strategies (9 items), affective strategies (6 items), and social strategies (6 items).

3) Horwitz's (1987) Beliefs about Language Learning Inventory (BALLI): It includes 34 items assessing learners' beliefs in five areas: 1) Foreign language aptitude, 2) the difficulty of language learning, 3) the nature of language learning, 4) learning and communication strategies and 5) motivations and expectations. The students were asked to choose a number on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1(strongly disagree) to 5(strongly agree) for BALLI.

The following procedure was followed to achieve the purpose of the present study.

First, 120 B.A and M.A Iranian EFL students with the aforementioned characteristics were selected. To remove possible anxiety, all the participants were informed about the purpose of the study.

Then, to make sure that there were no significant differences among the participants in terms of their proficiency level, a general proficiency test was administered. To homogenize the participants, their scores on the general proficiency test were summarized, and the mean and standard deviation were computed. The scores of those who scored between one standard deviation above and below the mean were selected, and the others were excluded from all subsequent analyses. The participants had 60 minutes to answer the proficiency test. At this stage, no questions were answered.

Finally, the strategies and control belief questionnaires were given to all participants. The participants had 45 minutes to complete these two questionnaires. The participants' questions about the items were answered.

To analyze the obtained data and to answer the research questions, 5 different multiple regression analyses were used.

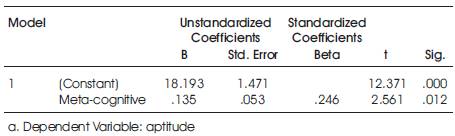

The first research question investigated types of language learning strategies as predictors of foreign language aptitude. To this end, a multiple regression procedure was used. Table 1 shows that, only meta-cognitive strategies entered into the regression equation. The other types of language learning strategies did not contribute to the regression model. Based on model summary (Table 1), it can be seen that meta-cognitive strategies and foreign language aptitude share 5.1% of the variance. In other words, meta-cognitive strategies explain 5.1% of the total variance in foreign language aptitude.

Table 1. Model Summaryc

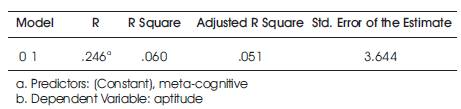

Table 2. Coefficientsa of language learning strategies

The standardized coefficient and the significance of the observed t-value for the predictor were checked to find out, how strong the relationship between foreign language aptitude and the predictor is. Table 2 shows the results.

Based on Table 2, meta-cognitive strategies account for a statistically significant portion of the variance in foreign language aptitude. Meta-cognitive strategies are the best predictors of foreign language aptitude; for every one standard deviation change in meta-cognitive strategies scores, there will be .24 of a standard deviation change in foreign language aptitude. It can be concluded that meta-cognitive strategies are positive predictors of foreign language aptitude test.

The second research question sought to investigate, which types of language learning strategies are better predictors of the difficulty of language learning. To answer this question, another multiple regression procedure was used. No variables entered into the equation.

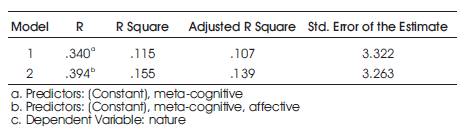

The third research question aimed to investigate, which types of language learning strategies are better predictors of the nature of language learning. A multiple regression procedure was used to answer this question. The stepwise multiple regression (Table 3) showed that meta-cognitive and affective strategies entered into the regression equation. Based on the model summary (Table 3), it can be seen that meta-cognitive strategies and nature of language learning share 10.7% of variance. Metacognitive and affective strategies together share 13.9% of the variance with the nature of language learning.

Table 3. Model Summaryc

To see how strong the relationship between the nature of language learning and the predictors is, the standardized coefficients and the significance of the observed t-values for each predictor were checked.

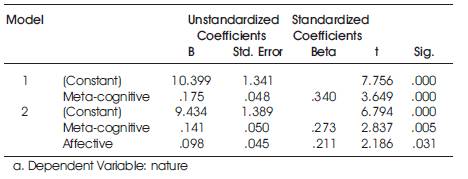

Table 4. Coefficientsa

Based on Table 4, meta-cognitive and affective strategies account for a statistically significant portion of the variance in foreign language aptitude. Meta-cognitive strategies are the best predictors of foreign language aptitude; for every one standard deviation change in meta-cognitive strategies scores, there will be .34 of a standard deviation change in the nature of foreign language. Affective strategies are another predictor of the nature of foreign language; for every one standard deviation change in the affective strategies scores, there will be .21 of a standard deviation change in the nature of foreign language. It can be concluded that, meta-cognitive and affective strategies are positive predictors of the nature of foreign language test scores.

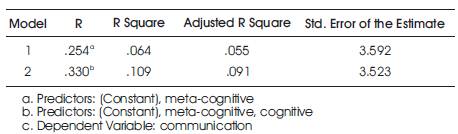

The aim of the fourth research question was to investigate, which types of language learning strategies are better predictors of communication. To this end, a stepwise multiple regression was run. Table 5 shows that metacognitive and cognitive strategies entered into the regression equation. Based on the model summary (Table 5), meta-cognitive strategies and learning and communication strategies share 5.5% of the variance. Meta-cognitive and cognitive strategies together share 9.1% of the variance with learning and communication strategies. In other words, meta-cognitive and cognitive strategies explain 9.1% of the total variance in learning and communication strategies.

Table 5. Model Summaryc

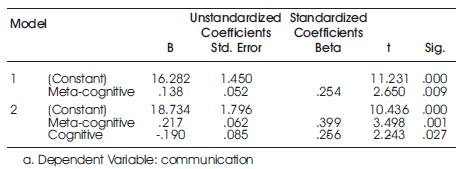

To see the strength of the relationship between the learning and communication strategies and the predictors, the standardized coefficients and the significance of the observed t-values for each predictor were checked.

Based on Table 6, meta-cognitive and cognitive strategies account for a statistically significant portion of the variance in learning and communication strategies. Meta-cognitive strategies are the best predictors of foreign language communication; for every one standard deviation change in meta-cognitive strategies scores, there will be .25 of a standard deviation change in the learning and communication strategies. Cognitive strategies are another predictor of the learning and communication strategies; every one standard deviation increase in the cognitive strategies scores, there will be .25 of a standard deviation decrease in the learning and communication strategies. It can be concluded that, meta-cognitive strategies are positive predictors and cognitive strategies are negative predictors of the learning and communication strategies.

Table 6. Coefficientsa

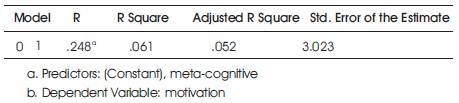

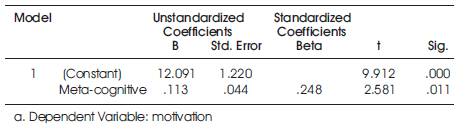

The fifth research question investigated, types of language learning strategies as predictors of motivation and expectation. A multiple regression procedure was used to answer this question. Table 7 shows that, only metacognitive strategies entered into the regression equation. Based on the model summary (Table 7), meta-cognitive strategies and motivation share 5.2% of the variance. In other words, meta-cognitive strategies explain 5.2% of the total variance in motivation and expectation.

Table 7. Model Summaryb

To see the strength of the relationship between motivation and the predictor, the standardized coefficient and the significance of the observed t-value for the predictor were checked.

Table 8. Coefficientsa of language learning strategies

Based on Table 8, meta-cognitive strategies account for a statistically significant portion of the variance in motivation and expectation. Meta-cognitive strategies are the best predictors of motivation; for every one standard deviation change in meta-cognitive strategies scores, there will be .24 of a standard deviation change in motivation. It can be concluded that meta-cognitive strategies are positive predictors of the motivation scores.

One of the findings of the present study was that metacognitive strategies were the best predictors of foreign language aptitude, nature of foreign language, learning and communication strategies, and motivation and expectation. Affective strategies were also predictors of the nature of foreign language. The participants employed more meta-cognitive strategies for foreign language aptitude, nature of foreign language, learning and communication strategies, and motivation and expectation in comparison to other categories of language learning strategies. This finding is in line with Rezaee and Almasian's (2007) findings, which showed that meta-cognitive learning strategies were the most preferred category of strategies for both high and low creativity groups. Also, this finding seems to be in accordance with that of Takeuchi (2003), who discovered that metacognitive learning strategies are employed more than other categories by successful language learners. Additionally, Sheroy (1999) and Radwan (2011) found that meta-cognitive strategies are used most frequently. In addition, Khaffafi Azar and Saeidi (2011), in their investigation into the relationship between EFL learners' beliefs about language learning and language learning strategies, found the strongest relationship between motivation and expectation and meta-cognitive strategies. Furthermore, the most notable correlation was between the overall BALLI and meta-cognitive strategies. In much the same vein, Yang (1999) found a connection between foreign language aptitude and meta-cognitive strategies. In addition, Khaffafi Azar and Saeidi (2011) examined the components of beliefs about language learning as predictors of language learning strategies and found foreign language aptitude and learning and communication strategies as predictors of language learning strategies. These two components were closely related to all types of language learning strategies. Hong's (2006) study on monolingual Korean students revealed that motivation and nature of learning English are closely related to meta-cognitive, memory, and compensation strategies. However, in his study, the correlation with compensation strategies was the strongest followed by meta-cognitive and memory strategies. Hong (2006) also found that Korean-Chinese students, who were instrumentally motivated and valued the nature of language learning, tended to use meta-cognitive strategies and cognitive strategies more than other strategies. This is in contrast with Oxford (1992), who found that cognitive strategies are the most popular strategies for language learners. Also, O'Malley et al. (1985) showed that cognitive learning strategies are used more regularly than meta-cognitive learning strategies by students. Furthermore, the findings of the present study contradict those of Khaffaf Azar and Saeidi's (2011) study, in which foreign language aptitude had the strongest relationship with general cognitive strategies and the nature of language learning had the highest negative correlation with social strategies. Furthermore, learning and communication strategies were strongly correlated with compensation strategies. This is also in contrast with Suwanarak's (2012) findings, wherein the strongest correlation was between the students' beliefs about motivation and the use of compensation strategies.

Another finding was that cognitive strategies were negative predictors of learning and communication strategies. The participants employed more cognitive strategies for learning and communication strategies in comparison to other categories of language learning strategies. This finding supports that of O'Malley et al. (1985), who showed that students used cognitive learning strategies far more regularly than meta-cognitive learning strategies. It also lends support to that of Chamot and O'Malley (1987), who revealed that students at all levels of instruction employed cognitive learning strategies to learn language. Also, Ehrman and Oxford (1995) discovered that cognitive strategies were most frequently used by successful language learners. Also, the finding of the present study is in contrast with Khaffafi Azar and Saeidi's (2011) findings in which learning and communication strategies were found to be highly correlated with compensation strategies. Khaffafi Azar and Saeidi (2011) also found that learning and communication strategies were better predictors of language learning strategies.

As another finding of the present study, it turned out that none of the language learning strategies were predictors of difficulty of language learning. In fact, no relationship was found between these variables. This is in contrast with Khaffafi Azar and Saeidi's (2011) study, in which difficulty of language learning was in correlation with meta-cognitive strategies and difficulty of language learning had a significant predicting power on the use of language learning strategies. It also contradicts the findings of Hong (2006) , who showed that the beliefs of the Korean-Chinese students had significant correlation with all the six strategy types; greater use of particular strategies depended on their pre-existing beliefs concerning language learning.

A number of factors could possibly account for these findings. The cultural differences might be one reason for the differences between the results of the present study and those of the above studies. Politzer and McGorarty (1985) and Chamot (2004) confirm the effect of culture on the choice of language learning strategies.

The differences in the learners' level of proficiency might also have affected their language learning strategy use. In this study, the participants were at upper-intermediate level. As a result, they may have been able to use indirect strategies such as meta-cognitive, affective, and social strategies and direct strategies such as cognitive and compensation strategies. Park (1997) and Yang (2007) have emphasized the role of level of proficiency in the choice of language learning strategies.

Gender differences may also be considered as another factor contributing to such differences in the findings. Gender differences were not taken into consideration in the present study, although they might have affected the learning strategy use and choice. Green and Oxford (1995), Zare (2010), Radwan (2011), and Sheorey (1999) emphasized the prominent role of gender differences in the choice of language learning strategies.

The age of the participant might be another factor contributing to such findings. In the present study, the age of the participant was not taken into consideration. Some researchers have investigated the use of strategies by young or adult learners and reached different conclusions regarding, whether younger learners adopt different sets of strategies in comparison to older learners (Chamot & El- Dinary, 1999; Wharton, 2000).

The present study attempted to investigate the types of language learning strategies as predictors of control belief. The results demonstrated that meta-cognitive strategies were significant predictors of 'foreign language aptitude', 'nature of foreign language learning', 'learning and communication strategies', and 'motivation and expectation'. Affective strategies also turned out to be predictors of 'the nature of foreign language'. Another finding was that, cognitive strategies were negative predictors of 'learning and communication strategies'.

Based on their knowledge of learners' beliefs and learning strategies, teachers can develop a clearer understanding of why students hold particular beliefs about language learning and use certain strategies. Teachers and learners together can plan activities to relate learners' beliefs about language learning and their language learning strategy use. This study is also beneficial for materials developers and syllabus designers. They can use the findings to develop materials and course books to improve the types of language learning strategies which are directly related to beliefs about language learning. Furthermore, it is very important that the teachers' teaching methodology be compatible with learners' beliefs.