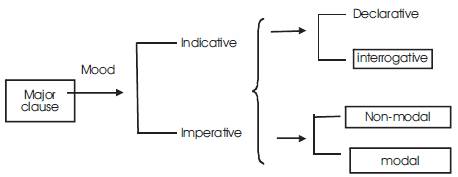

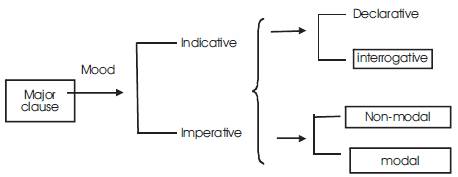

Figure1. Basic Mood Networking by Halliday

Although language is not power, it encodes power. This is the case with some speeches of former Nigerian President, Olusegun Obasanjo. This paper attempts to unravel the hidden ideological expression of power using critical discourse analysis (CDA) and systemic functional linguistics. Precisely, the paper draws on [1]Fairclough's (2001) members' resources and [1]Halliday's (1970) system of mood and modality as theoretical basis. The data comprise Obasanjo's addresses to public servants and the Nigerian Labour Congress (NLC) in 1978 and 2000 respectively. These are representative of the two political dispensations under which Obasanjo served. The findings show that Obasanjo deploys language as a strategy of suppression by exploiting lexical items with negative expressive values to stifle oppositions as well as make them unpopular. Also, the use of power as strategy of domination is mainly achieved through imperatives which allow the speaker to impose his opinion on others. In addition, declaratives are used to neutralise the asymmetrical power relation that exists between Obasanjo and the Nigerian Labour Congress. Obasanjo's militaristic trait of suppression and domination lends credence to his raw manifestation of power.

Power has been viewed as an abstract concept (Thomas and Wareing, 1999). However, it is equated with influence and control ( Brockeriede, 1971; van Dijk, 1993, 1996; Oha, 1994; Fairclough, 2001). From these assertions, power could be viewed as the ability to direct and constrain the behaviour of others. Power is encoded in the ideological workings of language and ideology is invested at all levels of language. The features or levels of language which are ideologically invested include all aspects of meaning: lexical meaning, presuppositions, implicatures, coherence, entailment etc. and formal features of texts. This paper is interested in how lexical choices as well as mood and modality are deployed as tools for encoding power in Obasanjo's speeches.

In relation to the functioning of power, Oha (1994:110) avers that “to understand how power functions as a constraint in discourse, we need to consider the differences between the social roles of the speakers and their audiences, and the implications of such social roles for discourse roles.” The social role that exists between a political public figure, like the president, and his/her subjects is that of a ruler and the ruled. The president has power as a result of the power or authority vested in him. Hence, this authority or power is seen as 'natural' and even when such power is deployed to dominate, suppress or oppress, it is usually not visible because it has become 'natural' and commonsensical.

Most studies on power in discourse have focused more on face-to-face interaction like doctor-patient interaction, doctor-medical student interaction and other forms of dialogic communication ( Fairclough, 1992, 2001; Ribeiro, 1996; Bloomer, Griffiths, and Morrison, 2005). This paper, differing from others, investigates the functions of linguistic features that are used to encode power in Obasanjo's speeches. It aims at unmasking the aspect of power in Obasanjo's address to public servants and the NLC with a view to determining the interpersonal component and linguistic features that instantiate power in his speeches. Obasanjo is seen as a controversial figure in Nigerian politics. This could be based on the fact that he was a former military head of state who, years later, became a civilian president. As such, he has served in the highest position of authority in Nigeria thus his use of language in encoding power is worth studying. Therefore this paper explores, from Fairclough's perspective of CDA and Halliday's systemic functional linguistics, those linguistic variables that encode power in the speeches.

This paper draws on CDA and systemic functional linguistics as theoretical basis. The study of implicit ideology is a major preoccupation of CDA; a theory that seeks to unravel connections between discourse practices, social practices, and social structures, connections that may be opaque to text consumers. CDA tries to “unmask ideologically permeated and often obscured structures of power, political control, and dominance ... in language in use” ( Wodak, de Cillia, Reisigl, and Liebhart, 1999:8). Fairclough is one of the proponents of CDA and his approach is considered appropriate to this paper. There is an aspect of sociocognition in Fairclough's approach which he calls members' resources (MR) which deals with aspect of text production and interpretation (Fairclough, 2001). MR is very crucial to our analysis in this paper.

Though the approaches of these scholars differ, their major focus has been of studying implicit ideology in discourse. Ideologies are 'common-sense' assumptions that people bring into the production and interpretation of texts (Fairclough, 2001). In order to uncover these assumptions, Fairclough (1992, 1995, 2001) resorts to an eclectic approach that incorporates both the productive and interpretative processes of text analysis. Formal traces of texts could be traces of the productive process which serve as cues in the process of interpretation (Fairclough, 2001). Also, MR is drawn upon in the process of interpretation. MR refers to background knowledge which is drawn upon to interpret texts (Fairclough, 2001). This background knowledge is cognitive because it resides in people's head. According to Fairclough (2001:20), “people internalize what is socially produced and made available to them, and use this internalized MR to engage in their social practice including discourse.” MR, which is brought into the process of production and interpretation, is implicit. Such implicitness is usually contained in taken-for-granted background knowledge. Background knowledge subsumes 'naturalized' ideological representations (Fairclough, 2001). These ideological representations take the form of non-ideological common sense which is best achieved through the process of 'naturalization' and 'naturalization' is the twin brother of opacity. It gives ideological representations the status of common sense and makes them become invisible as ideologies.

The implicit nature of ideology helps in sustaining power relations. In this regard, Fairclough (2001:2) argues that “the exercise of power...is increasingly achieved through ideology, and more particularly through the ideological workings of language.” According to him, “language/ ideology issues ought to figure in the wider framework of theories and analysis of power” (Fairclough, 1995:70). In analysing power in discourse, van Dijk (1996) opines that attention should be given to the description and explanation of how power abuse is enacted, reproduced or legitimised. Labourdette (2007:15-16) observes that power “sometimes dominates and some other times frees.” He further states that “the concept of power entails a connotation of force and abuse which hides other liberating and opposing characteristics” Labourdette (2007:16). Also, Habermas (1977: 259) states that "language is also a medium of domination and social force. It serves to legitimize relations of organised power. Insofar as the legitimations of power relations [...] are not articulated [...] language is also ideological."

Halliday's interpersonal function is relevant to the study of power in speeches. The interpersonal component is concerned with the expression of the speaker's 'angle': his/her attitude and judgments, his/her encoding of the role relationships in the situation, and his/her motive in saying anything at all (Halliday and Hasan, 1976). This functional component is represented by mood and modality (Halliday, 1978). Mood system is also related to the textual function of the semantic system (Halliday, 1970). Modality (the use of modals in stating the degrees of probability in discourse) relates to the interpersonal function of Halliday's metafunction. Aside the use of modals in stating the degree of probability in discourse, they are also used for the 'modulation' of process. This, according to Halliday (1970:336) has “nothing to do with the speaker's assessment of probabilities.” 'Modulation' of process expresses inclination and ability, permission and necessity (obligation and compulsion).

In order to identify the functions of mood in this paper, it is useful to refer to Hallidayan mood network as represented by Butler (1985:52).(Figure 1).

Figure1. Basic Mood Networking by Halliday

Mood are realised by some basic speech functions. These are command, statement and question. The speech function of command, statement and question are realised typically by the mood system of imperative, declarative and interrogatives (Ventola, 1988). The deployment of a particular mood type is based on the discourse role that a speaker assumes at a particular point in time. A speaker could assume the role of a declarer, a questioner or one who directs and regulates the thought and behaviour of others. Also, Muir (1972) incorporates speech function and modality as aspects of mood. Haratyan (2011:263) points out that “speech-functional roles help meaning to be achieved through mood....” Thus, speech functions, realised through mood together with modality are micro-level that could serve as tool in encoding power in the speeches under investigation.

The analysis focuses on two levels that obtain the unpacking of ideology. These are: micro and macro levels of analysis. The micro level is concerned with the analysis of lexical choices in the speeches while the macro level concentrates on the communicative situation and the function(s) the speeches are meant to perform. A critical insight into the lexical choices, mood and modality deployed in the speeches as well as their various communicative functions unearths the power relations hidden in the speeches. Hence, this paper looks at power as strategies of suppression, domination and liberalism. These shall be discussed in turn.

The 'unlimited' power enjoyed by the speaker as head of state is evident in the way he tries to stifle all forms of oppositions. This is a clear demonstration of power that results from the position the speaker occupies. The power relation, here, is one between an 'all powerful' head of state and the less powerful public servants. The extract below illustrates this:

“This Administration has taken some measures which are seemingly unpalatable to public servants and their reaction in the face of criticisms emanating from distorted vision and selfish hearts has ranged from culpable claim of ignorance, through joining the gullible crowd in the condemnation of Government policies to outright disinterestedness. (Address to Public Servants, 1978)”

In Ex. 1, some lexical items in relation to the source of the public servants' reaction have been identified. These are 'distorted vision' and 'selfish hearts'. These words mirror the speaker's text production strategy. To him, the criticisms are unhealthy because of their source. The reaction of the public servants to government policies is said to have its source from 'distorted vision' and 'selfish hearts'. A 'distorted vision' connotes a vision that has been twisted out of place while 'selfish hearts' is one that is self centred. He chooses 'distorted vision' to show the disapproval the critics gave to the 'good' measures taken by his administration. This implies that their vision is not clear and, for this reason, they cannot see beyond their present gains. If their vision were to be clear, they would have seen far into the 'good' intention of the government. The use of such emotive adjectives as 'distorted', 'selfish', 'culpable', 'ignorance' and 'gullible' bears negative connotations and this is an attempt to stifle criticisms. Moreover, the speaker claims that the outcome of the reaction of the public servants which emanates from unhealthy criticisms include culpable claim of ignorance, joining the gullible crowd in condemning government policies and outright disinterestedness. There is something very interesting in the speaker's choice of collocates: 'culpable' collocates with 'claim', 'gullible' collocates with 'crowd' and 'outright' collocates with 'disinterestedness'. As a semantic device, collocation deals with the co-occurrence of lexical items and as well aids the interpretation of texts. The lexical items 'culpable', 'gullible', and 'outright' are all adjectives and are deployed to strategically position the critics of the speaker's administration in negative angle. In essence, the ideology of the 'other' is viewed as distorted and selfish. That, supported by culpable, ignorance and gullible, suggests that the speaker treats 'distorted' and 'selfish' as synonyms to 'culpable', 'ignorance' and 'gullible' and, thus, imposes this 'common-sense assumption on the public servants.

Moreover, in Ex. 2 below, the speaker also tries to suppress all forms of criticisms and oppositions.

“I am here not to stay at all costs but to serve the people diligently, honestly, transparently, committedly and selflessly for as long as God wants me to. But on no account will I succumb to blackmail, character assassination, threats and intimidation, especially from those who have neither the character nor the reputation which a time like this demands. (Address to the Nigerian Labour Congress, 2000)”

That the speaker is not interested to stay in government at all costs arises from the text producer's MR of the deeds of some past presidents who never wanted to relinquish power. The excerpt above was made barely a year after the speaker assumed office as Nigeria's fourth republic president. Implicitly, this declaration by the speaker is meant to project him as new breed. The lexical items 'serve', 'diligently', 'honestly', 'transparently', 'commitedly', and 'selflessly' have positive significations. The speaker chooses these lexical items to self-categorise himself in positive light before the Nigerian Labour Congress and the Nigerian populace who constitute the larger audience. Thus, 'serve', 'diligently', 'honestly', 'transparently', 'committedly', and 'selflessly' are self-promotional. This has become a routine, naturalised way by which politicians try to gain acceptance.

The expression 'for as long as God wants me to' demands some critical investigation. The text producer understands that Nigerians have some form of religious sensibility and thus brings this into the discourse. By capitalising on this shared religious knowledge, the expression implicitly suggests that it is only God that can determine the length of time the speaker would be serving. This presupposes that no human being can determine the speaker's length of stay. In other words, the length of time the speaker would be serving can only be determined by God. In essence, no human being can challenge what God has put in place. The 'God factor' implies that the speaker sees himself as god-sent, a messiah who is sent to deliver Nigeria and no one needs to question his policies just as no man has the right to question God. The expression 'on no account' is a raw demonstration of power. This interpersonal cue is that of an authoritarian figure. This is a carryover of the speaker's militaristic trait.

This militaristic tendency is grounded in the speaker's military background. Obasanjo served in the United Nations (UN) peacekeeping mission in the former Zaire and he was the commander of the 3rd Marine Commando Division during Nigeria's 30-month Civil War (1967-1970). He was appointed works and housing minister in 1975 and later became chief of staff, supreme headquarters. Between 1976 and 1976, he became Nigeria's military ruler following the assassination of Murtala Muhammad.

This is a strategy deployed by the speaker to show the supremacy of a particular view or belief over that of others. This is illustrated in Ex. 3:

“At this juncture let me specially call on our University administrators to give serious consideration to development of African character and personality in our youths. Be enterprising and develop new norms relevant to our society rather than imbibe foreign norms lock, stock and barrel under the guise of universality of education. (Address to Public Servants, 1978)”.

The first instance of dominance is reflected in the lexical items 'me' and 'call'. This is a way of drawing attention to the personality of the speaker. The asymmetrical power relation between the speaker and the university administrators is best revealed in the word 'call'. By implication, it is the 'all powerful' head of state calling on the 'powerless university administrators' to see things his way. The singular call on the university administrators is ideologically loaded. This call emanates from the speaker's ideological point of view that the university is a place where foreign norms are developed in youths. The implication of the speaker's use of the imperatives is part of the linguistic coding of the speaker-audience (Oha, 1994:253) relations. The imperative mood in the first part of the excerpt portrays the 'unlimited' power he enjoys as a military head of state. The choice of the imperative mood signifies an obligation to be carried out by university administrators. Another instance of the use of the imperative mood is found in the second part of the extract which also suggests obligation. The lexical items 'African' and 'foreign' deserve some critical considerations. They are adjectives and are, also, antonymous. The antonymous relation between 'African' and 'foreign' captures the speaker's dichotomous cognitive assumption about the trainings university administrators have been imparting in the youths. Implicitly, this suggests that university administrators have concentrated on the development of norms that are alien instead of imparting indigenous character and personality in youths. This, as revealed in the excerpt, is done under the 'guise' of universality of education. The lexical item 'guise' portrays the speaker's justification of the claim that the workings of university administrators have not been all that relevant. The deployment of imperative mood by the speaker enables him to portray his views as one to be desired over that of the university administrators.

Another instance of the deployment of power as strategy of domination is shown in Ex. 4:

“Let no University be used as a hatching ground for violent political campaigns, destruction of political opponents and de-stabilisation of the society....Let our University teachers think and teach constructively, let them and their students bring forth new positive ideas for the improvement of the society and not negative ones for destroying the society. (Address to Public Servants,1978)”.

Ex. 4 abounds with preponderance of the imperative mood. The imperative mood in the extract serves the speech function of command. The use of the imperatives by the speaker is one way of enacting power. It is a direct enactment or production of dominance and its consequence is to manage the affairs of the university. The first imperative originates from the assumption the text producer brings into the text production. The assumption is that the university is a birthplace of violent political campaigns, destruction of political opponents and de-stabilisation of the society. This assumption is not unconnected with the speaker's reference to history. In 1978, there was a withdrawal of tuition fee in tertiary institutions in Nigeria by the government and this action led to a nationwide students' protest tagged “Ali Must Go” (Aluede, Jimoh, Agwinede, and Omoregie, 2005). 'Ali' in 'Ali Must Go' stands for the name of the then Minister of Education. ‘Ali Must Go' therefore suggests that the minister of education is not capable of handling such position and for that reason, he should resign.

The protest led to the closure of some universities and the dismissal of some university officials and students. Thus, the speaker's deployment of 'hatching ground', which is an intertextual mix of the sub-genre of agriculture, only serves to buttress the speaker's assumption that the university is the birthplace of unethical democratic practices. The lexicalisation of 'a hatching ground' only reaffirms the text producer's intention for choosing the material from that generic source. Also, the expressive values of such lexical items as 'violent', 'destruction' and 'de-stabilisation' as evident in the extract are negative. These negative connotations presuppose the speaker's ideologically based beliefs which have some connections with 'hatching ground'. The second imperative presupposes that university teachers have not been thinking and teaching constructively. This implies that since the university teachers cannot think constructively, there is no how their teachings could be constructive, hence, the production of the third imperative. This is enacted in the word 'positive' which has a synonymous relationship with the lexical item 'constructive'. These imperatives are used by the speaker to pre-determine the behaviour of the university teachers as well as their students to ensure desired action. Likewise their use arises out of an attempt by the speaker to exhibit his supremacy over the university teachers as well as the students. By using the imperatives, the speaker imposes his opinions on the university teachers and the students. Furthermore, the ideological difference between the speaker and members of the university community (comprising the university teachers and the students) is best revealed in the speaker's pronominal selection. The use of 'them' and 'their' is an indication that the speaker, the university teachers and the students belong to different ideological positions. This fact only reinforces the age-long 'war' between the 'men' in uniform and the intelligentsia.

A speaker uses power to liberalise when she/he does not impose any constraint on the audience. In such situation, the basic concern of such speaker is to express her/his intention and give room for the audience to freely make their decisions or choices of the views or opinions to embrace. This is illustrated in Ex. 5.

“The labour of our hand is not only meant to fetch us our daily bread, it is also meant to clean and sanitise our surrounding and beautify our environment. (Address to the Nigerian Labour Congress, 2000)”.

The speaker's use of declarative in Ex. 5 seemingly makes no specific claims about power relation. As evident in the extract, authority is not emphasised. The choice of declarative has a way of neutralising the power or authority of the speaker. The context in which the extract above is produced actually plays a major role in the text producer's deployment of this mood type. A new democratic dispensation has just been ushered in barely a year after many years of military dictatorship. This, actually, plays a major role in the text production. The speaker assumes the role of a declarer who only declares his views without imposing them on the NLC. The speaker uses the pronoun 'our' to show a form of camaraderie between him and members of the NLC. The pronouns 'our' and 'us' is meant to negotiate an in-group identity between the speaker and the NLC. Besides, 'our' and 'us' suggest a kind of corporate ideology that stresses the unity of a people at the expense of divisions of interest. Besides, their use is meant to give positive and united image of the speaker and the NLC. Furthermore, the effect of 'our' and 'us' is to treat, in a casual manner, the unequal power relation that exists between the speaker and members of the NLC. It is an attempt by the speaker to bridge the power gap between him and the NLC. With this, the speaker only presents his opinions as suggestions.

Another instance where the speaker uses power to liberalise is shown in Ex. 6:

“...together we can make democracy succeed such that all Nigerians can earn democracy dividend. (Address to the Nigerian Labour Congress, 2000)”.

'Together' and 'we' have some correlation. They both suggest joint effort. This is also a strategy used by the speaker to show a sense of collective responsibility between the NLC and himself. The speaker uses the pronoun 'we' inclusively. The inclusive use of 'we' is relationally significant in that it represents the speaker and the NLC as being in the same boat. Pronominal referencing is therefore strongly deployed in the discourse to index group alignment and identity. This serves as an appeal to ideological common sense. The speaker's appeal to ideological common sense stems from the speaker's background knowledge of the important position the NLC occupies in the country. In addition, the speaker chooses the modal 'can' to suggest the possibility and capability of the success of democracy through the joint effort of the speaker and the NLC. This implies that the speaker may not be able to record great feat without positively associating with the NLC in the democratic process. The effect of the speaker's appeal to ideological common sense makes him to present the possibility of the success of democracy in Nigeria without imposing his view or opinion on the NLC.

The study reveals that power is deployed as strategy of suppression through the enactment of lexical items with negative expressive value. The choice of words with negative connotations is an attempt by the speaker to suppress all forms of oppositions and make them look unpopular. Power as dominance is mainly achieved through imperatives which enable the speaker to impose his opinions on others. The use of power as strategies of domination and suppression is more evident in Ex. 1, 2, 3 and 4. Ex. 1, 3 and 4 are excerpts from 1978 speech whereas Ex. 2 is from the speech made in 2000. Power as liberalism is mainly achieved through the use of declaratives as evident in Ex. 5 and 6. The speaker deploys declaratives to neutralise the asymmetrical power relation that exists between him and the NLC. This is further achieved through the speaker's pronominal selection that allows the speaker to create an in-group ideology with the NLC. The speaker's use of both declaratives and pronominal reference allows him to play down on his authority and, thus, give room for no imposition. Thus, Obasanjo's use of language portrays him as someone with authoritarian disposition (as indicated in power as suppression and domination). However, his authoritarian disposition is milder as a civilian president as could be seen in power as liberalism.