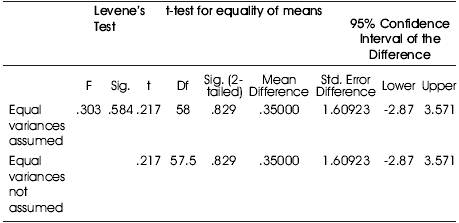

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of the Two Groups Prior to the Treatment

This research compared the effect of using dictogloss and dicto-phrase tasks on EFL learners' listening comprehension. To fulfill the purpose of the study, a piloted sample Key English Test (KET) was administered to a total number of 90 Iranian female teenage EFL learners at Kish Language School, Tehran, and then 60 were selected based on their performance. The selected participants were then assigned into two experimental groups: dictogloss and dicto-phrase group. In one group, the dictogloss tasks and in the other dicto-phrase tasks were practiced through 10 sessions and at the end of the course, all the participants were given the listening section of another piloted sample KET as a posttest to measure their listening comprehension. Subsequently, the mean scores of both groups on the posttest were compared through an independent samples t-test which led to the rejection of the null hypothesis demonstrating that the learners in the dictogloss group outperformed the dicto-phrase group significantly in terms of listening comprehension. In other words, the dictogloss task was more effective on students' listening comprehension compared to the dicto-phrase task.

Listening comprehension plays a crucial role not only in daily communication but also in language teaching and learning. In the case of language learning, understanding the spoken language requires a sequential arrangement of activities to be developed, namely discriminating the sounds, perceiving the message, holding the message in auditory memory and finally comprehending it. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that comprehension is beyond simply processing every word and it is about understanding the speaker's intended meaning (Agarwal, 2008; Brown & Yule, 1983;Hargie, 2010;Noordin, Shamshiri, & Ismail, 2012; Page & Page, 2011; Verderber, Verderber & Sellnow, 2011).

Rizvi and Kapoor (2010, p. 91) state that, “Listening is a complex process of perceiving and interpreting the sounds correctly, as well as understanding the explicit and implied meaning of the oral message”. Rizvi (2005, p. 71) further states that comprehending a verbal message calls for the listener's ability to “identify main ideas, and supporting details, understand long speeches, identify the formality level, and deduce unfamiliar vocabulary and incomplete information”. All this is perhaps what makes listening “the most difficult skill to learn out of the four skills” (Usó-Juan, & Martínez-Flor, 2006, p. 29).

The importance of listening in language learning is paramount as “most of the time is spent on learning through listening” (Tyagi & Misra, 2011, p. 195). The information required to build and use language is achieved through listening. A learner listens, gets information, and then starts speaking. In other words, listening provides the basis for other language skills such as speaking (Kianiparsa & Vali, 2010; Modi, 1991; Nation & Newton, 2009).

Based on research, of the total communication time, 16 percent takes the form of reading, nine percent writing, 30 percent speaking, and 45 percent listening (Fujishin, 2007). Nevertheless, the importance of listening in interpersonal communication relationships and second language programs is often ignored still regarded by some as a passive skill while the more efficient approach would be to encourage the learner “to concentrate on an active process of listening for meanings, using not only the linguistic cues but his nonlinguistic knowledge as well” (Fang, 2008, pp. 21-22).

Realistic listening thence requires an employment of appropriate listening texts and tasks among which dictation has proved to help improve listening skills (Delmonte, 2008;Farshid, & Farshid, 2010; Kiany & Shiramiry, 2002; Ndiforchu, 2011; Ur, 1984). Among the variations on dictation such as standard or full dictation, partial dictation – dicto-comp and dictogloss – are “very popular with teachers and students” (Nation & Newton, 2009, p. 59).

Dictogloss, which Wajnryb (1990) developed from dictation, has received attention in second language learning classrooms. Wajnryb argues that dictogloss tasks are practical listening activities in task-based language teaching which embody the four steps of preparation, dictation, reconstruction, and analysis besides correction. Through these steps, learners listen to a short text read twice to them by the teacher and take notes. Then they reconstruct the text in small groups and finally analyze and correct their texts (through which the learners receive feedback). Dictogloss requires the students to maintain as much information as po ssible and produce “grammatically accurate, textually cohesive, and logically sensible” texts (Wajnryb, p. 10).

Dictogloss tasks are meaning-based tasks aimed at processing the meaning more deeply rather than simply passing the input straight through short-term memory as in standard dictation. Wajnryb (1990) also states that, “Learners who regularly engage in dictogloss lesson gradually see a refinement in their global aural comprehension and note-taking skills” (p. 7). In other words, in dictogloss tasks, learners not only listen to the teacher for understanding the text but are also obliged to listen to other learners while working in groups to reconstruct the text in addition to practicing taking notes.

Along with the practicality of dictogloss as a type of meaning-based collaborative dictation task that enhances listening development (Brisk & Harrington, 2007; Nassaji & Fotos, 2011; Ranta & Lyster, 2007; Wajnryb, 1990), dicto-phrase (Zahedi, 2004) is a rather recent type of dictation that is noteworthy in teaching listening. Zahedi (2004)states that dicto-phrase or dictation-paraphrase is “an interface between teaching and testing which makes it an appropriate tool for tapping listening abilities for classroom purposes” (p. 107). He adds that dicto-phrase tasks are gist-getting tasks designed to give learners the opportunity to reproduce the propositions of language in their own words while concentrating on the content of the idea units. In other words, in dicto-phrase tasks after listening to the passage, learners are given a passage with blanks to complete with the gist of the meaning of the missing propositions rather than the exact replacement of the lexical phrases of the original text (Laleh-Parvar & Zahedi, 2007).

Moreover, the blanks are accompanied by wh-questions in brackets in order to help learners with recalling the information. Dicto-phrase tasks originate from real-life situations such as sending an email to a friend to tell them about some news they have heard for instance (Zahedi, 2004). Therefore, the texts chosen for dicto-phrase tasks are normally authentic to encourage learners to listen attentively.

Dictogloss and dicto-phrase then, as two different types of dictation, are observed as practical means of listening improvement in classrooms (Vasiljevic 2010) through which authentic materials can be incorporated. Both dictation types, that require understanding the meaning of the passage, provide the opportunity for learners to practice reproducing propositions of a dictated passage in their own words through the integration of listening and writing (Wajnryb, 1990; Zahedi 2004).

Regarding the issues of collaboration and note-taking in dictogloss, Storch (2002) states that the whole procedure of dictogloss is interactive and student-centered. When learners work in small groups to reconstruct the text, they tend to feel less intimidated and together they nurture individual responsibility and positive collaboration. On the contrary, dicto-phrase tasks are not concerned with collaboration and do not permit note-taking; rather, they require the reconstruction of the idea units of the passage the learners listen to, in which long term memory and recalling the information are of great importance. Laleh- Parvar and Zahedi (2004) demonstrated that dicto-phrase tasks diminish the role of short term memory and boost the role of long term memory in making responses. They also found that the most significant strategies employed by the participants, while performing on dicto-phrase, were rereading and intelligent (not random) guessing.

In line with what has been discussed so far on the vital role of listening in language learning and the fact that both dictogloss and dicto-phrase tasks have proved to improve listening, the present study aimed to compare the effectiveness of these two dictation tasks on listening and particularly find the more effective one. Accordingly, the following research hypothesis was raised:

H0 : There is no significant difference between the impact of dictogloss and dicto-phrase tasks on EFL learners' listening comprehension.

The participants in this study were 60 Iranian female EFL learners in a language school in Tehran. All participants were aged between 14 and 17 and at the preintermediate level of language proficiency who attended a 21-session course held two days a week, each session lasting for one hour and a half. The participants were selected among 90 pre-intermediate students at the same language school based on their scores on a language proficiency test previously piloted among 30 learners with the very much similar language background. The 60 participants who obtained a score of one standard deviation above and below the mean among the 90 who sat for the test were selected and subsequently assigned randomly into the two experimental groups with 30 participants in each.

To carry out the present study, the researchers employed a number of instrumentations as tests, scoring rubrics, and instructional materials discussed below.

A piloted mock Key English Test (KET) designed by Cambridge was used as a language proficiency test in order to select the sample for the study. This test was used to make a homogeneous sample in terms of the language proficiency level.

The main course book used in both groups was “Pacesetter” by Strange and Hall (2005), which is designed specifically for teenagers with a communicative approach that presents the new language in contexts relevant to teenagers and in ways which actively involve them in the learning process. Every unit of the book covers all four language skills as well as pronunciation and vocabulary to develop the learners' fluency and confidence in understanding and using English.

For this particular study, 10 texts suitable in length and difficulty level for the learners in both groups were adopted from various sources and covered in 10 sessions during the 21-session course in each group. The texts used in both groups were the same and related to the topics of their course book: sports, our world, environmental problems, food, street markets, hoaxes, theme restaurants, diet, health, and global language. The difference between the two groups lay in the procedure of teaching the texts, details of which appear in the procedure section below. The listening paper of another sample piloted KET was used as the posttest and administered to both groups at the end of the course.

Following the selection of the participants and the random assignment of the two experimental groups with 30 participants in each group (a total of four classes), the treatment, which was conducted by one of the researchers as the teacher of both groups, commenced. As the teacher had to accommodate the treatments into the usual program of the course, she allocated 10 out of the 21 sessions of the course to the treatments in each experimental group. Dictogloss and dicto-phrase, as the treatments, were practiced every other session in each class with the teacher introducing the tasks to the participants in each group in the first session.

In one experimental group, dictogloss and in the other dicto-phrase were practiced as the treatments. For this study, the same 10 texts (described in the instrumentation section) were used. In the dictogloss group, the teacher went through four stages in the classroom: preparation, dictation, reconstruction, and analysis with correction. In the first stage, the teacher prepared the learners for the text they were supposed to listen to by asking questions and engaging the learners in very short discussions on the topic.

Meanwhile she pre-taught any necessary words related to the text and wrote them on the board and ensured that the learners knew what they were supposed to do. Then the board was erased before the actual listening started so that the listening part of the task was challenging enough.

After the preparation, in the second stage which was the dictation, the learners listened to an audio recording of the text three times without any pauses. The first time, they just listened and got a general feeling of the text. The second and third time, they took down notes as they were encouraged to listen for content words which assisted them in reconstructing the text.

At the conclusion of the dictation, learners went through the third stage: reconstruction. The learners were put in groups of three and asked to reconstruct the text in about 10 minutes. Learners pooled their notes and produced their own written version of the text from their shared resources. This reconstruction aimed to retain the meaning and form of the original text but was not a word-for-word copy of the text they listened to. Instead, students worked in groups to create a cohesive text with correct grammar. During this stage, the teacher did not provide any language input.

In the final stage of the task, the learners spent about 10 minutes on analyzing and correcting their texts. They compared their text with the reconstructions of other learners and the original text and made any necessary corrections.

In the dicto-phrase group, the teacher also went through the four stages of preparation, dictation, reconstruction, and analysis with correction. In the first stage, like the dictogloss, she introduced the topic of the upcoming text and let the learners find out about the topic by asking some questions about it and having a very short discussion. She also did some preparatory vocabulary work and wrote the new words on the board and ensured that the learners knew what they were supposed to do. Then she erased the board before the actual listening started.

After the preparation, the learners went through the dictation stage. The learners listened to an audio recording of the text three times without any pauses. The first time, they just listened and got a general feeling of the text. The second and third time, unlike the dictogloss, the learners were asked just to listen and were not allowed to take notes. They were told that they would be given a passage after listening so they did not need to take notes, but they were encouraged to listen very carefully to get the details.

In the third stage, or reconstruction, the learners were given a passage with blanks and were asked to fill them with the gist of the meaning of the missing propositions and not necessarily the exact words. The blanks were also accompanied by wh-questions in brackets in order to help the learners with recalling the information. The blanks were meant to be filled with a phrase or a sentence. The learners worked individually in this section and spent nearly five minutes on reconstructing their stories.

Finally, in the analysis and correction stage, the learners compared their text with the reconstructions of other learners and the original text and made the necessary corrections. At the end of the course, the participants in both groups were given the posttest described earlier.

The details of the statistical analyses conducted to test the hypothesis of the study are presented in a chronological order of participants selection, posttest administration, and testing the hypothesis.

To select the participants required for this study, the researchers used a piloted KET, the reliability estimate of which was an acceptable Cronbach's Alpha Index of 0.849. Furthermore, the inter-rater reliability of the two raters scoring the writing parts of the KET was significant at the 0.01 level (r = 0.710) while that of the two raters scoring the speaking section was also significant at the above level (r = 0.711).

Once the 60 participants were selected from the 90 who took the test based on their scores falling one standard deviation above and below the mean, the selected participants were randomly assigned into two experimental groups of dictogloss and dicto-phrase. The descriptive statistics of the scores of the two groups on the proficiency test appear in Table 1. As is clear, the mean and the standard deviation of the dictogloss group prior to the treatment were 70.53 and 6.50, respectively, while those of the dicto-phrase group stood at 70.18 and 5.95, respectively.

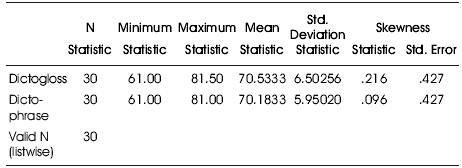

Prior to the treatment, to ensure that the two groups displayed no significant difference on the whole in terms of their language proficiency, a comparison of the means had to be conducted to see whether there was a significant difference between the mean score of each group. Consequently, an independent samples t-test was required.

With the skewness ratios of both groups being 0.50 (0.216 / 0.427) and 0.22 (0.096 / 0.427) and both values falling within the range of -1.96 and 1.96, the normality of distribution within each group was guaranteed. Table 2 includes the results of the t-test run between the mean scores of the two groups on the proficiency test.

The results (t = 0.217, p = 0.829 > 0.05) indicate that there was no significant difference between the mean scores of the two groups at the outset. Hence, the researchers could rest assured that both groups manifested no significant difference in their language proficiency prior to the treatment.

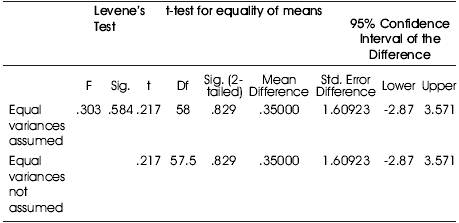

Once the treatment in each group was over, the pilote listening posttest comprising 25 items which enjoyed a reliability of 0.71 was conducted. Table 3 contains the group statistics for this administration with the mean and standard deviation of the dictogloss group standing at 18.10 and 3.60, respectively, while those of the dictophrase group were 16.23 and 3.41, respectively.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of the Two Groups Prior to the Treatment

Table 2 Independent Samples t-Test of the Two Groups' Mean Scores on the Proficiency Test

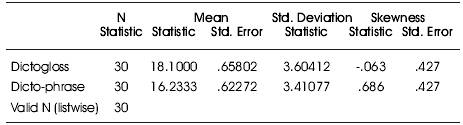

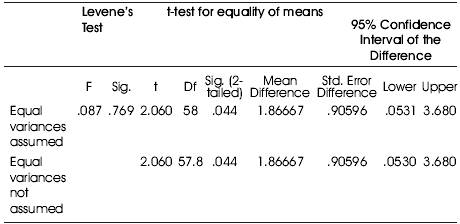

To demonstrate any possible significant difference in the performances of the dictogloss and dicto-phrase group and to test the null hypothesis of the study, the researchers conducted an independent samples t-test. Again, the skewness ratios resembled normalcy of the scores (-0.14 and 1.60) and thus running a t-test was legitimized.

Based on Table 4 (t = 2.060, df = 58, p = 0.044 < 0.05, two-tailed), there was a significant difference between the mean scores of the two groups at the posttest. Thus, by virtue of the means that the two groups obtained, it is evident that the dictogloss group outperformed the dictophrase group. In other words, it can be concluded that the presupposed null hypothesis was rejected meaning that the difference observed between sample means was large enough to be attributed to the differences between the population means and therefore not due to sampling errors.

To determine the strength of the findings of the research, that is, to evaluate the stability of the research findings across samples, effect size was also estimated to be 0.53. According to Cohen (1988, p. 22), this is a moderate effect size. Therefore, the findings of the study could be moderately generalized.

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics of the Posttest

Table 4. Independent Samples t-Test of the Two Groups' Mean Scores on the Posttest

The results of the present study can be interpreted in line with the findings of Jacobs and Small (2003) and Vasiljevic (2010) that dictogloss is not only a practical means of listening improvement in classrooms but also offers numerous potential advantages over other models of listening comprehension such as the integration of all four language skills, engaging learners in authentic communication, and encouraging cooperation among learners, as well as self and peer-assessment.

As Jacobs and Small (2003) note and as reconsolidated in this study, the dictogloss method combines conventional teaching procedures such as topical warm-up, explicit vocabulary instruction, and possibly grammar correction with a new type of meaning-based listening activity. A dictogloss listening class embodies several important principles of language learning such as learner autonomy, cooperation among learners, focus on meaning, and self and peer-assessment.

In dictogloss, learners work cooperatively, that is to say that they work together not only to maximize their own learning but also to maximize the learning of all other group members (Johnson & Johnson, 1999; Marashi & Baygzadeh, 2010). To this end, the researchers clearly observed that the learners were actively involved in doing the dictogloss activities cooperatively. While practicing and using all modes of language, learners were engaged in authentic communication and were helping one another. Dictogloss tasks provided learners with enough time to become familiar with the intended topic in each session and that they were engaged in the tasks and seemed to be enjoying it.

The dictogloss procedure involved learners in both decoding and encoding the message and observed during the instruction, it enhanced their listening as well as their writing and communication skills. It pushed learners to produce a meaningful text while cooperating with other learners. The task provided learners with a sense of achievement and encouraged them to think about the process of their language learning.

The abovementioned finding presents some important implications for teaching listening comprehension to syllabus designers, teachers, and learners that favor speaking along with listening. First and foremost, English language teachers can help learners benefit from dictogloss in their classrooms. Regarding the collaborative nature of dictogloss, teachers can use these tasks in the classroom to raise learners' motivation in their own learning and that of their classmates, while working in groups.

One of the issues that teachers face in teaching listening in classrooms is the inappropriateness of the listening contents/scripts in regards of culture, age, or the needs of the learners. Using dictogloss, teachers can replace the content with a proper one and then read it to the class. It allows the teacher to match the listening content with the needs of the learners and also helps learners get motivated to listen.

The findings of this research can also help syllabus designers and textbook writers to raise learners' interest in listening. Regarding most learners' preference for speaking, and lack of interest in listening and probably writing, syllabus designers can include more dictogloss tasks, so that learners get motivated to do the listening tasks. In other words, dictogloss tasks can be inserted into textbooks to engage learners not only in listening but also in taking notes, speaking and writing a paragraph cooperatively, and finally reading their paragraph, i.e. the integration of all four language skills.

Besides, syllabus designers can take advantage of a host of variations on dictogloss task types and hence avoid monotony in listening tasks.

To conclude, the researchers would like to offer the following two suggestions for further research.