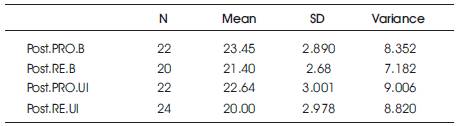

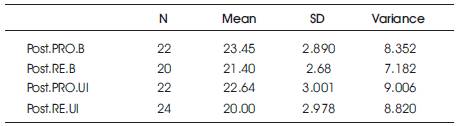

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of the Grammar Posttest

Recently ELT has witnessed the debate between the proponents of non-interventionist and interventionist views towards SLA. The former, also known as zero option, sees L2 acquisition as an incidental process leaving no role for instruction (Krashen, 1981; Prbhu, 1987), while the latter considers instruction effective and even crucial for some learner types (i.e., adults and EFL learners with insufficient L2 exposure), some grammatical structures, and achieving higher levels of grammatical accuracy (Dekeyser, 2000; Doughty, 2003). Research has shown that instruction does facilitate the process of L2 learning, especially when juxtaposed with high amounts of exposure (Ellis, 2006). Consequently, different versions of form-focused instruction (FFI) are being practiced despite the fashionable meaning-focused instruction (MFI) of the communicative era. Nevertheless, a question still remains: “when is the time to intervene?” The present research targeting this very question compared the efficacy of proactive and reactive FOF on the grammar improvement of 88 Iranian EFL learners at two proficiency levels of beginner and upper-intermediate. The results indicated that regardless of the proficiency level, proactive FOF was more effective on the grammar improvement of the participants when compared to reactive FOF. The researchers strongly believe that in EFL settings like Iran with minimum amount of exposure, planned grammar instruction is a necessity.

The role of grammar teaching is one of the most debatable issues in language teaching. In the early years of the twentieth century the crucial part of language instruction was grammar teaching, while other aspects were either ignored or down played (Richards and Renandya, 2002). During that time, as Ellis (2006) states, "grammar teaching was viewed as the presentation and practice of discrete grammatical structures" (p. 84), which inevitably required learners to memorize grammar rules. He considers this approach to grammar as somewhat narrow on the grounds that there are different possibilities for a grammar lesson: (i) having presentation and practice, (ii) giving practice and no presentation, (iii) leading learners to discover grammatical rules on their own with no presentation and practice, (iv) exposing learners to input containing multiple exemplars of the target structure, and finally (v) providing corrective feedback on learners' errors while performing communicative tasks. Nevertheless, “for most teachers, the main idea of grammar teaching is to help learners internalize the structures taught in such a way that they can be used in everyday communication. To this end, the learners are provided with opportunities to practice the structures, first under controlled conditions, and then under more normal communicative conditions (Ellis, 2002, p. 168).

Richards and Renandya (2002) believe that” in recent years, grammar teaching has regained its rightful place, in language curriculum; people now agree that grammar is too important to be ignored, and without a good knowledge of grammar, learner's language development will be severely constrained” (p. 145). In the same line, Ellis (2005) warns that acquiring language naturally without any form-focused instruction would not allow adult L2 to achieve full target language competence, especially because there seem to be some linguistic properties that cannot be acquired without instruction and assistance.

According to Ellis, Loewen, and Basturkmen (2002), a close analysis of the discussions on how to teach grammar indicates that they usually center around the possible pedagogical options available to teachers and the relative benefits of each for learners. They complain that not enough “attention has been paid to the actual methodological procedures that teachers use to focus on form in the course of their actual teaching” (pp. 419-420). Nevertheless, the status of grammar-focused teaching or, as it is currently referred to, form-focused instruction is undergoing some major reassessments (Richards and Renandya, 2002) leading to the re-introduction of some very basic questions such as “should we teach grammar?”, “when should we teach grammar?”, and “what grammar should we teach?” (Ellis, 2001; Ellis, Loewen, & Basturkmen, 2002; Ellis, 2006); however, there seems to be a unanimous agreement on the answer to the question of whether to teach grammar or not. In fact, within a communicative framework, the question is now only concerned with the “how” and “when” of the grammar teaching. This research aims to address the second question.

In the 1980s and 1990s, classroom research reported positive results for grammar instruction. Although, the traditional methods of teaching grammar did not return, techniques were developed whereby students would be able to “notice” grammar, often spontaneously in the course of a communicative lesson, and especially if the grammatical problem impeded comprehension (Brouk, 2008). Thornbury (2000) holds that communicative competence develops as learners communicate through exchanging meanings, and “grammar is a way of tidying these meanings up” (p. 25). As a result, he adds, the teacher's responsibility is to provide opportunities for authentic language use which would inevitably require learners to employ grammar as a source rather than as an end in itself.

Ellis, Loewen, and Basturkmen (2002) believe that grammar teaching should be more vivid: Learners are able to acquire linguistic forms without any instructional intervention. They typically do not achieve very high levels of linguistic competence from entirely meaning-centered instruction. For example, students in immersion program in Canada failed to acquire such features as verb tense markings even after many years of study. (p. 421).

Nevertheless, it has been also argued that “learners do not always acquire what they have been taught and that for grammar instruction to be effective it needs to take account of how learners develop their interlanguage” (Ellis, 2006, p. 86). Many studies were conducted to compare the success of instructed and naturalistic learners (e.g. Long, 1983) and to examine whether teaching specific grammatical structure resulted in their acquisition. The results showed that naturalistic learners achieved lower levels of grammatical competence than instructed learners and that instruction was no guarantee that learners would acquire what they have been taught. Thornbury (2000) contends that:

Grammar teaching -that is attention to forms of the language- lies in the domain of learning and, says Krashen, has little or no influence on language acquisition. More recently research suggests that without some attention to form, learners run the risk of fossilization. A focus on form does not necessarily mean a return to drill-and-repeat type methods of teaching. Nor does it mean the use of an off-the-shelf grammar syllabus…….. (p. 24).

In other words, as Brouke (2008) suggests, the purpose is to encourage learners to construct their own grammar through their own language experience which would in turn allow them to restructure their emerging interlanguage either consciously or subconsciously.

Spada (2010) claims that “there is increasing evidence that instruction, including explicit FFI, can positively contribute to unanalyzed spontaneous production, its benefits not being restricted to controlled/analyzed L2 knowledge” (p. 9). Recently, FFI is considered more useful and effective than the instruction that only focuses on meaning (Foto & Nassaji, 2007). Spada (1997) defines FFI as “any pedagogical effort which is used to draw the learners' attention to form either implicitly or explicitly . . . within meaning-based approaches to L2 instruction [and] in which a focus on language is provided in either spontaneous or predetermined ways” (p. 73). Thornbury (2000) states that “if the teacher uses techniques that direct the learner's attention to form, and if the teacher provides activities that promote awareness of grammar, learning seems to result” (p. 24). In other words, explicit attention to form can facilitate second language learning (Norris & Ortega, 2000).

In Spada's review (2010) of research on FFI, she identified many studies which compared groups of learners with and without FFI. In these experiments, all groups did receive communicative instruction but some with exclusively meaning-based teaching (i.e. no FFI) and others with some attention to language forms (i.e. FFI). Some studies indicated benefits for FFI (e.g. White, 1991; Lyster, 1994) while others did not (e.g. White, 1998). Also, some studies revealed benefits for FFI in the short term but not in the long term (e.g. White, 1991).

As mentioned earlier, there are various taxonomies in teaching of grammar the most important of which is the distinction between focus on form (FOF) and focus on forms (FOFS). FOFS is very much reminiscent of the traditional view to grammar teaching while FOF under the influence of the meaning-focused instruction involves drawing the learner's attention to linguistic form as they incidentally focus on meaning (Long, 1991). Doughty and Williams (1998) elaborate on the two approaches:

It appears to be generally accepted that a structuralist, synthetic approach to language, characterizes Focus on Forms where the primary focus of classroom activity is on language forms rather than the meanings they convey. Focus on Form, in contrast, consists of an occasional shift of attention to linguistic code features—by the teacher or one or more students. (p. 23)

In simpler terms, FOF consists of an occasional shift of attention to linguistic code features, by the teacher and/or one or more students, triggered by perceived problems with comprehension or production (Long & Robinson, 1998). This shift of attention occurs as a result of an interruption in the flow of communication (Long, 1988). Moreover, FOF is defined as any planned or incidental instructional activities that are intended to induce language learners to pay attention to linguistic forms (Ellis, 2001). Ellis, Leowen, and Basturkmen (2006) explain that ”focus on form is evident in the talk arising from communicative tasks in sequences where there is some kind of communication breakdown and in sequences where there is no communication problem but nevertheless the participants choose to engage in attention to form” (p. 135). Thus, a FOF approach is valid as long as it includes an opportunity for learners to practice behavior in communicative tasks (Ellis, 2006).

As a whole, according to Doughty and Williams (1998), the FOF approach provides learners an advantage over FOFS since it draws learners' attention precisely only to the linguistic features that are demanded for communication. (Ellis, 2006) mentions that there is growing evidence that focus-on-form instruction facilitates acquisition, though it is not possible to prove the superiority of one over the other.

Doughty and Williams (1998) in their extensive discussion of focus on form, make the distinction between proactive and reactive focus on form. Both approaches seek to focus on language forms in a communicative context. Proactive or preemptive FOF involves preplanned instruction designed to enable students to notice and to use target language features that might otherwise not be used or even noticed in classroom discourse (Lyster, 2007). Doughty and Williams (1998) think that for a proactive approach, one has to make informed predictions or carry out some observations to determine the learning problems of the students. Long and Robinson (1998) believe that by taking this stance, there is no need to undergo the burdensome process of selecting learner errors which are frequent, systematic, and remediable at that particular stage. Doughty and Williams (1998) state:

Proactive focus on form is where the teacher chooses a form in advance to present to students in order to help them complete a communicative task. This can be done explicitly through formal instruction, while a less explicit focus might involve asking students to alter or manipulate a text that contains a target form. This differs from traditional grammar instruction as the grammar focus is not centered on a set of language structures imposed by the syllabus. Instead the choice of form is determined by the communicative needs of the learners. The choice of forms is also influenced by other factors such as individual learner differences, developmental language learning sequences, and L1 influences. (p. 198).

The following is an example of an implicit focus on form given by Willis and Willis (2007, p. 96):

What advice would you give to the person who wrote this letter? Discuss your ideas and then agree on the two best suggestions.

Dear Angie,

My husband and I are worried about our daughter. She refuses to do anything we tell her to do and is very rude to us. Also, she has become very friendly with a girl we don't like. We don't trust her anymore because she is always lying to us. Are we pushing her away from us? We don't know what to do, and we were worried that she is going to get into trouble.

Worried parents

They elaborate that on a task like this individuals should jot down their two pieces of advice, discuss them before presenting them to the class, draft a letter of advice, and finally read and evaluate each other's final draft. They suggest that learners would encounter many phrases expressing negativity and work on classifying them according to some structural criteria which would in turn provide them with a rich learning opportunity.

Ellis, Basturkmen, and Loewen (2002, p. 428-429) provide examples of explicit proactive FOF. In the first example, they explain, the teacher is preparing the setting for a communicative activity in which the students have to come up with an alibi for a crime. As the teacher predicts that the students may not know the meaning of alibi, she directly poses a question. This can be considered as a typical example of pre-emptive FOF often directed at the meaning of lexical items that interrupt the activity.

Teacher initiated focus-on-form (using a query)

T: what's an alibi?

T: M has an alibi

T: another name for girlfriend? (laughter)

T: an alibi is a reason you have for not being at the bank robbery (.) okay (.) not being at the bank robbery

In the second example, they refer to student-initiated FOF. They explain that the student is trying to remember the word 'translation' as a vocabulary learning strategy and when she can't, she resorts to the communication strategy of 'requesting assistance' which eventually leads to the elicitation of the word from the teacher:

Student-initiated pre-emptive focus-on-form

S: T, how do you <>

T: what?

S: English and? (2) the only word?

T: the other language?

S: yes, the onway language, how?

T: I don't know, what was the other language?

S: no, no s-, I'm saying this um, con-, con-

T: translation?

S: translation, thank you

T: translation, yeah

S: translation, conlation (laughs) ah

T: and the translation, good

It can be seen that in both kinds of proactive focus-on-form, as they argue, “the participants took time-out from communicating to topicalize some linguistic feature or item as an object” (p. 427).

Reactive focus on form, however, refers to a responsive teaching intervention that involves occasional shifts in reaction to important errors with the help of devices that increase perceptual saliency (Long & Robinson, 1998). Doughty and Williams (1998) state that “reactive focus on form involves developing the ability to notice pervasive errors and have techniques for drawing learner's attention to them (p. 211). Lyster (2007) contends that reactive form-focused instruction allows learners to put into practice what they have learned from proactive instructional activities while they are having a purposeful interaction. Hence, he thinks, reactive form-focused instruction has to appear in the form of corrective feedback and any other attempts aimed at drawing learners' attention to language form during interaction.

Thornbury (2004) finds reactive teaching is more effective than proactive teaching. He argues that it is easier to follow each learner's developmental trajectory by responding to their communicative errors rather than to pre-emt the errors through pre teaching. He then elaborates on a typical example of reactive FOF in which each learner asks their partner questions about their last weekend in five minutes and then spends five minutes writing a paragraph. The teacher then collects the texts and prepares a list of 15 to 20 sentences to focus on their tense and aspects. The next session, the learners will be asked to work in small groups or pairs to select well formed sentences and correct the wrong ones.

As it can be seen, reactive focus on form is a treatment which deals more specifically with student output where the focus is on structures that students themselves have used, or have tried to use, during a communicative task (Mennim, 2003). In simpler terms, reactive instruction of grammar entails responding to communication problems of the learners occurring after the event (Long & Robinson, 1998). Willis and Willis (2007, p. 121) put forth three major characteristics for reactive FOF:

Many studies have been conducted to examine the efficacy of alternatives of FOF. For instance Doughty and Verela (1998) examined the differences in the acquisition of English tense between junior ESL science students who received corrective recasts and those who received teacher-led instruction or proactive instruction mostly in the form of lectures. Regardless of the type of instruction they were exposed to, learners took pretests and posttests. Those students who received corrective recasts performed significantly better on posttests than did those who received teacher-led or proactive instruction. In another study, Van Patten and Oikkenon (1996) investigated the effects of processing instruction on a group of secondary students studying Spanish at the intermediate level. Processing instruction involves an explicit explanation of a certain grammatical rule followed by contextualized practice activities. Participants were divided into three groups: one group received explicit explanations of rules, one received contextualized practice activities, and the other one received both explicit explanations of rules and contextualized practice activities. They found that those who only received explicit explanations retained the fewest grammatical rules; the other two groups, on the other hand, achieved significantly higher scores on post-treatment tests.

In a descriptive study, Basturkmen, Loewen, and Ellis (2002) explored episodes of classroom interaction in which there was unplanned attention to form. The data consisted of periodic recordings of learners in intensive English classes, as well as periodic testing of forms that emerged as a focus of attention during these episodes. Analysis of the data revealed that there was a strong connection between attention to form and subsequent use of those forms. It further showed that this connection was affected by the proficiency level of the learners On the whole they concluded that learners play an important role in promoting the establishment of form-meaning connections and attention to form can arise in a variety of ways such as in learners' requests for assistance, learner–learner negotiations, and feedback on errors.

Ellis, Basturkmen, and Loewen (2002), based on theoretical as well as empirical reasons, assert that the teacher's role in a communicative task is twofold, acting as a communicative partner while paying attention to form when needed.

This study was a quasi-experimental one because random sampling was not feasible. The dependent variable of grammatical proficiency measured with an interval scale, the independent variable of FOF type with two conditions of proactive and reactive, and the moderator variable of language proficiency level with two conditions of beginner and upper-intermediate lead to the formation of two sets of pretest-posttest nonequivalent-groups design.

The participants of this study were 88 Iranian female EFL learners studying at beginner and upper-intermediate levels of a language school in Tehran, Iran. They attended their language course three times a week. They were adults with an age range of 18 to 43; nevertheless, the majority was in their late 20's and early 30's. At the beginner level, there were 42 participants, 22 in the experimental group 1 and 20 in the experimental group 2. Similarly at the upper-intermediate level, there were 46 participants, 22 in the experimental group 1 and 24 in the experimental group 2. At both levels, Group 1 received proactive FOF and Group 2, reactive FOF.

Three types of tests were used in this study:

1. The general proficiency test of Key English Test (KET) adopted from http:www.tesol.org.com was administered to beginners. The speaking section of the package was not conducted due to practical problems. The listening and reading sections were proved to enjoy a satisfactory reliability. As for the writing section, the inter-rater reliability of the two expert examiners of the language school was calculated also indicating a satisfactory index.

2. For the upper-intermediate participants, the listening and reading sections of First Certificate in English (FCE) were used as an indication of the general proficiency of this group of participants.

3. Two grammar tests (one for beginners and the other for upper intermediates) including 30 three-choice items were constructed based on the grammatical points covered during the instruction. Content quality analysis as well as CRT item analysis and reliability were employed to check the efficacy of the items. It is imperative to mention that the two tests were used as both the pretest and posttest at the two levels.

American Cutting Edge books, Levels 1 and 4, were used respectively for the beginner and upper-intermediate levels. The level 1 book has 12 units with each four unit taught in one term. , The beginners of this study worked on the second four units of the book. The grammar points included in the syllabus of the beginners included possessive's, present simple, yes/no questions (present simple), wh-questions (present simple), subject and object pronouns, adverbs of frequency, time expressions (on Monday, in the morning…), can/can't, and wh-question words (who, when, ...). The level 4 book has 12 units with each four unit covered in one term for the upper-intermediate levels. The last four units were instructed in the upper-intermediate groups of this study. The grammar points of this level were considered making predictions (will, won't, etc.), real/hypothetical possibilities with if, past perfect with time words (when, after, etc.), reported and directed speech, obligation and permission (can, must, have to, etc.), linking words (although, however, etc.), and finally post modal verbs (could have, should have, would have).

There were five classes, two beginners and three upper-intermediates. The general proficiency tests of Key English Test (KET) for beginner and for upper-intermediate participants the First Certificate in English (FCE) were used to make sure of the equality of two groups at each level. Next, in order to measure learners' grammar knowledge as a baseline level, i.e., before treatment, pretests were administered to both experimental groups at two levels.

The classes were held in 22 sessions, 20 minutes of which was allocated to grammar instruction. It is important to mention that this period was automatically extended in the reactive group, meaning that problem shooting took longer than a preemptive covering of the predetermined grammatical structures of every session.

In the proactive groups, at both levels of beginner and upper-intermediate, the teacher preselected the grammar points and introduced them through integration with the communicative context. For example for constructing real/hypothetical possibilities, first, the teacher talked about her unreal wishes and wrote some of them on the board. Then, she highlighted the hypothetical words and structures and explained them to the learners. Next the learners were asked to write four unreal wishes on the paper. Finally, they corrected each other's papers and shared their ideas. For the next session the teacher asked them to write about the unreal wishes of a famous person and be ready to talk about them in class.

In the reactive groups, the teacher responded to the learner's errors while they were communicating. The teacher, for example, would set a simple pair work communicative task in which one member of the pair had to write a paragraph about their partner's last weekend after asking as many question as needed within 10 minutes. For the next session, the teacher with regard to say tense and aspects would select 15 to 20 sentences from the learners' collected papers. Some of the sentences would be well-formed and some of course ill-formed. She would copy them onto the board and ask learners working in small groups or pairs to select well formed sentences and correct the others.

The grammar achievement posttests were administered to both groups as the end of the treatment to evaluate their knowledge gain throughout the instruction. With the independent variable of FOF type, the moderator variable of language proficiency level, and the dependent variable of grammar knowledge of an interval nature, the statistical tests employed were limited to the parametric test of independent-groups t-test based on the assumption of normality of the distributions.

Prior to the treatment, the two experimental groups at both levels of beginner and upper-intermediate were examined statistically to belong to the same population in terms of general proficiency as well as the knowledge of the grammatical points to be instructed during the course. After the treatment, both groups sat for the same grammar achievement test as the posttest. Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of all four groups on their grammar posttest.

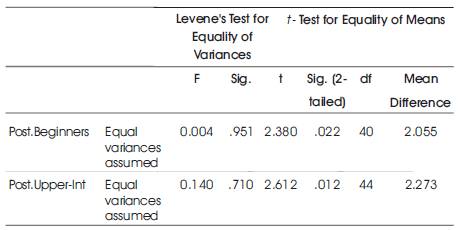

Table 2 demonstrates the independent-samples t-tests conducted to compare the means of the proactive and reactive groups at the two levels of beginner and upper-intermediate. The Levene's test of the beginners and the upper-intermediates with F (1, 40) = 0.004, p = 0.951 (two-tailed) and F (1, 44) = 0.140, p = 0.710 (two-tailed) respectively indicated that the t-tests could be conducted with variances assumed equal.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of the Grammar Posttest

Table 2. Comparing Grammar Posttests of the Proactive and Reactive Groups at Two Proficiency Levels

The t-test conducted between the beginner proactive (M= 23.45, SD = 2.89) and reactive groups (M= 21.40, SD = 2.68) resulted in t(40) = 2.38. p =.022 (two-tailed), indicating that there was a significant difference between the means of the two groups at the end of the treatment. Similarly, the researchers found a significant difference between the scores of the proactive group (M= 22.64, SD = 3.001) and the reactive group (M= 20.00, SD = 2.798) at the upper-intermediate level with t(44) = 2.612. p =.012 (two-tailed) .

The result of the present study indicated that proactive and reactive instruction of grammar had different impacts at both levels of upper-intermediate and beginner on the grammar improvement of the participants of the study. To be more specific, learners who received proactive FOF improved significantly more than those learners who received reactive FOF at both levels. This finding is in accordance with that of Van Patten and Oikkenon (1996) who demonstrated that the employment of preemptive techniques result in better internalization of different linguistic forms. Nevertheless, quite expectedly, the result of this study contradicts some other studies such as the one done by Doughty and Verela (1998) who found that those learners who received corrective recasts performed significantly better on posttests than did those who received teacher-led or proactive instruction.

The close examination of the quantitative outcome of the present study in the light of the actual minute-to-minute experience of the teacher of the classes who happens to be one of the researchers has brought the attention of the authors to few possible reasons for the outperformance of the proactive group at both levels. The first reason could be the repeated opportunities for attention to the preselected grammar forms which were available in the proactive groups. Since reactive focus on form involves a responsive teaching intervention in the form of occasional shifts to important errors (Long & Robinson, 1998), it inevitably becomes more time consuming, giving fewer opportunities to elaborate on key grammar points of the lesson. This problem was particularly graver in the upper-intermediate group whose learners were not patient enough to allow the teacher to go over their errors one by one. In other words, as Ellis, Leowen, and Basturkmen (2002) had a similar observation, their continuous questioning did not allow the teacher or other students to react to their errors through explicit correction or the use of metalanguage to draw attentions to the problematic structures. This could be due to the fact that they preferred to know the target form as soon as possible, so they asked repeated questions about their erroneous forms. As an example, in one of the sessions, the teacher tried to put learners in a situation to ask questions with past perfect but two of the learners asked some questions about conditional sentences. Giving a brief explanation on conditional sentences limited the time that had to be spent on past perfect. In this regard, Thornbury (2000) believes that when it comes to grammatical explanations, the shorter the better. He suggests that “economy is a key factor in the training of technical skills….the more the instructor piles on instructions the more confused the trainee is likely to become” (p. 25). In proactive classes, however, the teacher could manage economy of grammatical explanations and hence the learners were more likely to notice the form that was being addressed.

Another reason which was more noticeable in the beginner reactive group was that due to procrastinating the elaboration of grammar forms after the learners committed errors, it inescapably exposed the learners to many erroneous forms during the communicative activities they performed. As a result, they tended to consider many of the erroneous forms as correct. In some cases, it took three to five sessions for the teacher to find the opportunity to correct them and make sure that the learners have grasped the correct form. Indeed, the proactive learners of grammar less than the reactive learners repeated other learner's errors. Therefore, it can be suggested that the pre-selection of grammar points in the proactive FOF prevented learners from fossilizing their peers' as well as their own erroneous forms.

The final reason may be related to a very distinctive feature of reactive classes which is the teacher's voluntary and/or involuntary deviation to erroneous forms which are not in the list of grammar forms that have to be treated in that very lesson. This usually happens as a result of the learners' preoccupation with the errors that are not to be discussed during that session or that course at all. It may be argued that this is one of the merits of reactive approach in that it allows for covering a wider range of grammatical forms. The counter argument presented here is the floating nature of the reactive FOF may eventually lead to a higher performance in a general grammar test, but when learners are to cover certain grammatical structures that are going to appear in an achievement grammar test, it is highly probable that some of the points get overshadowed by those errors that were not a part of the syllabus and hence are not to appear in the final test. We strongly believe that our reactive groups may unintentionally, despite the teacher's effort, have put themselves in a disadvantage by simultaneously focusing on a variety of forms which did not necessarily contribute to their performance on the final posttest.

This research addressed the efficacy of proactive and reactive instruction of grammar at two levels of beginner and upper-intermediate in the EFL setting of Iran. Among the possible reasons for the advantage of the proactive FOF over a reactive one, the authors highlighted three reasons of ample opportunity and time to focus on preselected forms ,less exposure to erroneous forms and hence less fossilization, and finally more syllabus-oriented instruction. Considering the fact that a lot of research has proven otherwise, the researchers suggest that the key may lie in the significant differences that exist between second and foreign language settings, particularly those like Iran's. A reactive explicit FOF is obviously supported and consolidated by the abundance of exposure available in ESL settings. In the majority of cases, learners get the chance to be receive corrective feedback on an error that they have committed a number of times in their real-life interactions and may have even noticed that they have been using an erroneous form. Hence the reactive treatment of the error acts as the last piece of puzzle they have been working on for quite sometimes. In an EFL setting with minimum exposure to English outside the classroom, quite often the learner is encountering a certain grammar point for the first time and even an extended treatment of an error which is usually committed by a peer is by no means sufficient for the internalization of its underlying rule. In conclusion, the researchers of this study find the proactive focus on form an indispensible technique in the teaching of complex infrequent structures in EFL settings impoverished in terms of exposure.